This is a three part interview series with Russian anti war activists: Ivan in Kazakhstan, Dima in Moscow, & Shamil in Dagestan.

Introduction

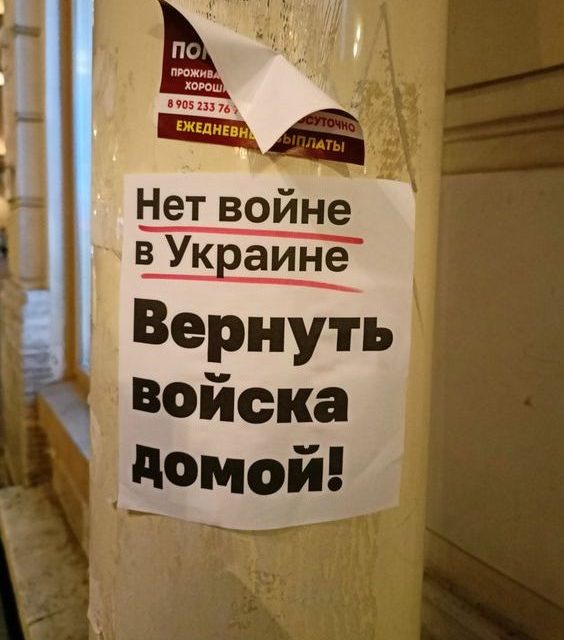

Russians have long suffered under Putin’s authoritarian, neoliberal regime with heavy surveillance and harsh penalties for dissent. On September 21st 2022, Putin announced a draft that could sweep 300,000 civilians into military service, bringing the war in Ukraine home to all Russians who are eligible, or know someone who is eligible, for military conscription. That is almost everyone.

And like all other ills under capitalism, the draft falls hardest on the poor, the working class, and on marginalized communities who have little money or power to evade it.

Commentators have expressed a wide spectrum of thought on what this will mean for Russians, Putin, and the Russian Left. Some herald the draft as the straw that will soon break the camel’s back, igniting revolution and the overthrow of Putin. Others see it as a move to further entrench and escalate both Putin’s power and Russia’s lurch towards right-wing nationalism. While no one can predict outcomes with total certainty, not even Russian activists still inside Russia, it is important that the global Left not germinate yet more useless silos of opinion. Instead, with both ears and both eyes open, we need to prioritize solidarity with the Russian left, seeking out their experiences, understanding their struggle, and supporting their self-determination.

The international Left claims that we celebrate and support Russian people’s refusal to fight in wars and that we support the Russian people’s political struggle against authoritarianism, oligarchy, and neoliberalism. We should therefore make it a priority to elevate the voices of these people in a direct way, and to let them help guide us in our solidarity.

Voices of resistance

Voices of Resistance is a collection of interviews conducted between October-December 2022, with young activists inside Russia who give their impressions and observations about resistance to authoritarianism & conscription, about the state of Left movements in Russia, and about what has changed over the course of this year.

Seven questions were proposed to each respondent, and their answers have been translated and lightly edited for clarity. All names have been changed and political affiliations have been kept vague to preserve anonymity. Each respondent is politically engaged and navigating tumultuous circumstances as they struggle to both survive and to build a better world.

All of the respondents are eligible for conscription.

Interview with Dima in Moscow

How would you describe your political involvement? Why did you agree to this interview?

I was most active in politics before the Lockdown and changes in personal circumstances, but I have been close to the Left political movement since 2012. We have some good people, but the movement itself is a little chaotic these days.

- On the ground in Russia:

What would you like people across the globe to understand about what is going on in Russia today? What are the conditions that you and others experience?

I would like to say: in Russia we have to work hard now. Harder than ever.

We feel a lot of new limitations. Since February 24th, we can not travel freely all around the world as cheap and easy as it was before. We have to choose: to leave our homes, our neighborhood, our families – or stay in Russia and try to make something better from the inside.

I think that it would be great if people around the globe understand that we are not part of our government.

- The Russian Left today:

Describe the state of the Left movement in Russia. What has changed over the course of this year? Has conscription had significant impact and if so, how?

It is really difficult to understand what is actually the Left movement in Russia.

We have liberal-minded people, soviet-minded and some radicals – and all of them are Left towards the current establishment.

This year was full of complicated problems.

In the first days of war, a lot of people made terrible decisions to flee in a panic: crashed their business, left their families, lost their friends.

The impact from the conscription was not as bad as the war itself – we were already terrified by the situation, so this new problem, to me, was not really newly terrifying.

The conscription had more impact on Russian families and couples and I think you can see here the power of women. I know a lot of men who left Russia because their partner or family was fearful for them and stopped everything and made every effort to get them out. A lot of people in Russia are just living their own lives without any politics, trying to survive. But if someone tells them “your husband or son will serve and he can die for his country” that changes quickly. I know several women who sent their husband to another country, with great expense and sacrifice, because of the conscription.

- Resistance to authoritarianism and to war:

What are your current thoughts about resistance to authoritarianism & to conscription? What has resistance meant for you and for others around you?

The resistance from inside an authoritarian country is to be a good human. Me and my friends are trying to do our best, even if we stay here with no dedicated purpose, or just because of low funds. Our goal is to make our country better by staying here, though for many they also stay because they don’t have the opportunity to leave.

I have such trivial plans: to build a home, raise my child, etc. – and I could do it in any country, but I really love my friends and my parents. I don’t want to lose my roots because of one insane man in our government.

- What Russian Leftists are trying to build and to do:

Are leftist and/or mutual aid organizations growing in ranks and commitment? If so, what are some notable examples?

I’m not really often communicating with Russian leftists outside my friends anymore, for now. I know that many people suffer for their human rights and spend a lot of time on this, but en masse, we don’t really feel any impact in our everyday life. And since the conscription started, I feel that we have no law, and surely it is not really safe to protect any position if it goes across the line of the government position.

We have “nice” government and establishment in Moscow and some other cities in Russia. But the Federal power is not as friendly and cute as the local authority.

- National consciousness:

Has there been any shift in national popular sentiment towards the war, towards Putin, and towards the hegemonic establishment over the course of this year? And even in these last weeks since the draft was announced? What sort of, if any, conversations are happening among people that question official narratives and institutions?

Over this year I met a lot of people and I heard a lot of discussion about the situation.

Of course, it was a great shift, and it still is not over. We will continue to feel strong repercussions over the years and it will likely remain as painful as the situation now.

Some of my friends became enemies. OK, maybe not enemies, but its created more and more divisions. Friends and family are becoming estranged or even enemies due to differences in politics and understandings of power relations. Some friends with different points of view (especially those, who mostly agree with Putin) raised the distance between us (people who are anti-war) and them. You know, no more birthday parties etc with these people. I know about a couple divorces because of different positions within families.

Others abandoned their lives and took great risks by fleeing. Some of them ran away and lost their work. Some people left their hometowns to run away from the conscription.

We are living in a historic time, just like people in The Black Obelisk felt in Germany before the Nazi’s got their full power.

- The view from Russia:

How are the actions of the West perceived by you and by other Russians?

As for me – everything is right: if your neighbor tries to use force instead of resolving problems by speaking about it – surely, let him know that he is not right.

It looks like human rights doesn’t mean anything for the Russian military – so OK, it’s time to let them know! The invasion is wrong. I think that any armed conflict is wrong.

Someone became richer because of this conflict, but I don’t know who exactly.

Many Russians are very upset about the response of the West, and I do understand them. We now have increased problems with lack of access to medicines, with a lot of technologies – it is dangerous to stop our global development and we feel this danger here. The people feel punished for their government’s actions.

- Internationalism and solidarity:

What would solidarity mean to you from both within Russia and from the global Left? How can fellow activists support your efforts and become advocates within their own countries?

From the outside, I don’t really know. I’m not competent enough to tell someone from the outside what to do. I will say that some other countries are helping by providing opportunities for Russian draft refusers and political dissidents to leave. This helps a lot. Some of my friends already left Russia to Latvia, Poland, Lithuania, Israel, Georgia – all these places help people to leave Russia.

It will help us if people all around the globe understand that Russian people and our government are not the same.

From the inside, I’d like to say to Russians: work hard, don’t listen to official politics, don’t watch TV and try to figure out what’s really going on.

Read parts 1 and 3 of this interview series with Russian anti war activists:

Part 1: Ivan in Kazakhstan

Part 3: Shamil in Dagestan

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate