Part One:

When I was initially asked to sign onto the Twenty Theses for Liberation, my first thought was, “Why not?” I knew the authors; I agreed with the sentiments. Signing on wasn’t going to cost me anything.

So I did.

Since then, having reread the document and taken some time to reflect, it’s hard not to be embarrassed by my reaction/attitude.

You know you’re cynical when you read something this comprehensive, urgent, and simultaneously hopeful and the most enthusiasm you can muster is, “It can’t hurt.” Yet I’m willing to bet I’m not alone. Not because there isn’t substance and inspiration to be found. But because we’re not sure we can really win.

How many of us are merely going through the motions, fighting the good fight, “contributing something,” with little to no expectations of it amounting to anything?

These feelings are instructive. Evidence of just how much we are up against. And, if we are honest, evidence of our own failures in movement building.

But if these failures are to be lessons, it’s imperative that we engage this call with more than just our signature.

This can’t be all we are. And the Twenty Theses isn’t just some petition on a clipboard.

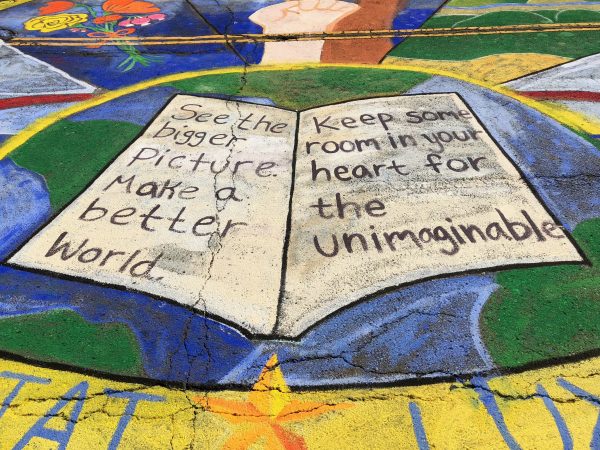

It’s a compass for our journey. And a promise that the place we seek is real.

Do you still believe that? Do you still believe there is real promise in humanity?

If so, we don’t need a map; we need each other. And we need a compass.

For the value in a compass is not merely in keeping your sense of direction. It’s about keeping your party together. A reference to cite in times of confusion or disagreement, or even despair. Something reliable and true.

That’s what I see in this document. I hope more people will give it serious attention and reflection.

Part Two:

As a signatory to the Twenty Theses for Liberation, my first act of engagement, if I may be so bold, would be to ask: Is it too early to embrace the call for refinement?

If not, I would like to make a suggestion for potential inclusion in a future addendum.

Thesis One (Foundations) lists polity, economy, kinship, culture, ecology, and international relations as central aims of attention for a long-term liberatory movement.

As I celebrate the holistic nature of this foundation, one thing I feel is missing from the list is Education.

Not that Education is missing from the document. It is included. But more so as a mention, alongside other aspects which make up the core aims. It is alluded to rather than focused upon.

If these Twenty Theses are meant to be instrumental to the trajectory we desire for a better world, what kinds of humans would a future like this require?

I acknowledge that wording, “what kinds of humans,” may be awkward. But the question is quite serious.

What kinds of humans would be capable of and adept to operating within political institutions free from elitism and domination?

What kinds of humans would be agreeable to an economy that aspires to classlessness and sees equity as a guiding principle?

What kinds of humans would be able to navigate kinship, gender, and sexual relations in a healthy manner? To embrace truly liberatory, non-hierarchical cultural and community relations?

It’s not just institutions we have to change. It’s us too.

The reason why so many are resistant to proposed alternatives, why so many have a hard time believing “human nature” would even allow for a just society, is because our minds have been conditioned from birth to accept current norms and expectations. To indeed believe these norms are a natural order.

Of course, this isn’t evidence of human nature. It’s a testimony to the impact our institutions have on our development.

So again, if we truly believe that our better world is possible, we must ask: What kinds of humans could ever pull all this off, much less thrive in such liberated institutions?

And by answering this question, we can begin to ask: What kind of educational model could aid in producing such humans?

Think of it like reverse engineering. No different from deciding upon an economic model by first asking what values we want to see manifested in the end result.

If we want healthy humans, curious and critically thinking humans, humans who can resolve disputes without resorting to violence, humans equipped to participate in a better polity, in a better economy, in better kinship, gender, sexual and cultural relations, then that’s what our education system should be about. Not preparing children to one day fill slots in a competition-based workforce so they may justify their survival and/or dignity.

We must build a model of learning based on experimenting and experiencing, guided by evidence and best practices, gained from careful yet ambitious trial and error.

We must seek a diverse array of interdisciplinary instructors. Teachers who see their empathy lessons every bit as important as, if not more important than, lessons on math and science. A curriculum that sees the foundation-forming of media literacy, cultural appreciation, and emotional intelligence/resilience as a requisite to engaging with literature, history, and civic/social studies.

Far beyond the capitalistic assembly line rehearsal we have become accustomed to, we must envision education that doesn’t end after twelve years and the optional degree, but rather extends throughout a life and beyond the walls of early schooling. An education that maintains the very capacity it has built, and continues to build. Equipping us for our kinship, community, and polity roles, in addition to our economic ones.

But before we can do this, we must acknowledge the teachings of our current institutions for what they are. For the lessons that have perpetuated centuries of racism, sexism, classism, homophobia, ableism, and every other form of hierarchical oppression are a form of abuse. And in the same manner we aspire to avoid the physical and mental legacy of childhood trauma, we must find a way to produce adults who do not recreate and pass on the same harmful behavior.

Our institutions will only be as good, will only be as solid, as the people who are expected to facilitate them and function within them. Unless we can equip the members of our communities to find their potential and contribute to society in ways that are both valuable and fulfilling, while simultaneously supporting others doing the same, there’s no reason to believe these institutions will produce the values and outcomes we desire.

For these reasons, I humbly recommend that Education be considered, in addendum or future iteration of the Theses, as an additional core element of strategic importance.

I offer this suggestion, not as a critique, but as a demonstration of the necessary, good faith participation needed if the current iteration of the Theses is to ultimately achieve its goals.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate