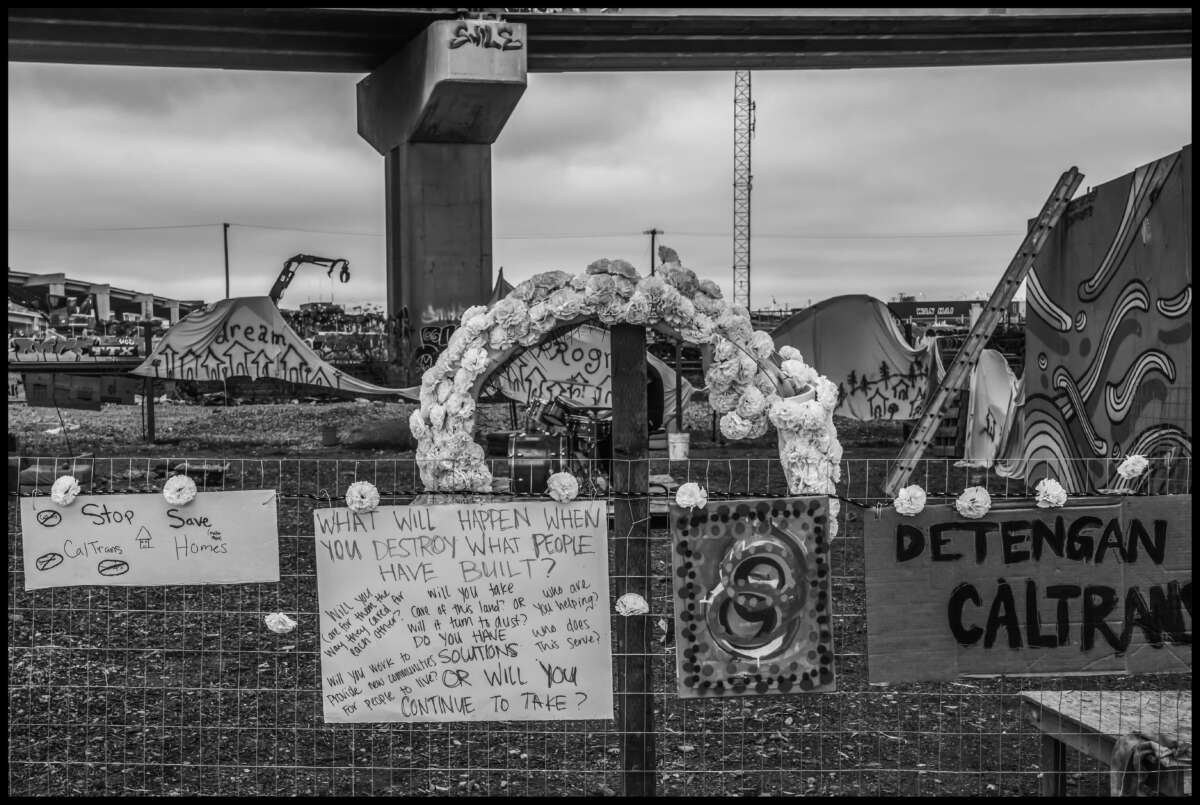

The words “housing is a human right” used to appear in bright colors on a painted placard at the gateway to Wood Street Commons, which until recently was the largest unhoused encampment in northern California. But this February, the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) demonstrated how vehemently it disagrees with the placard’s assertion.

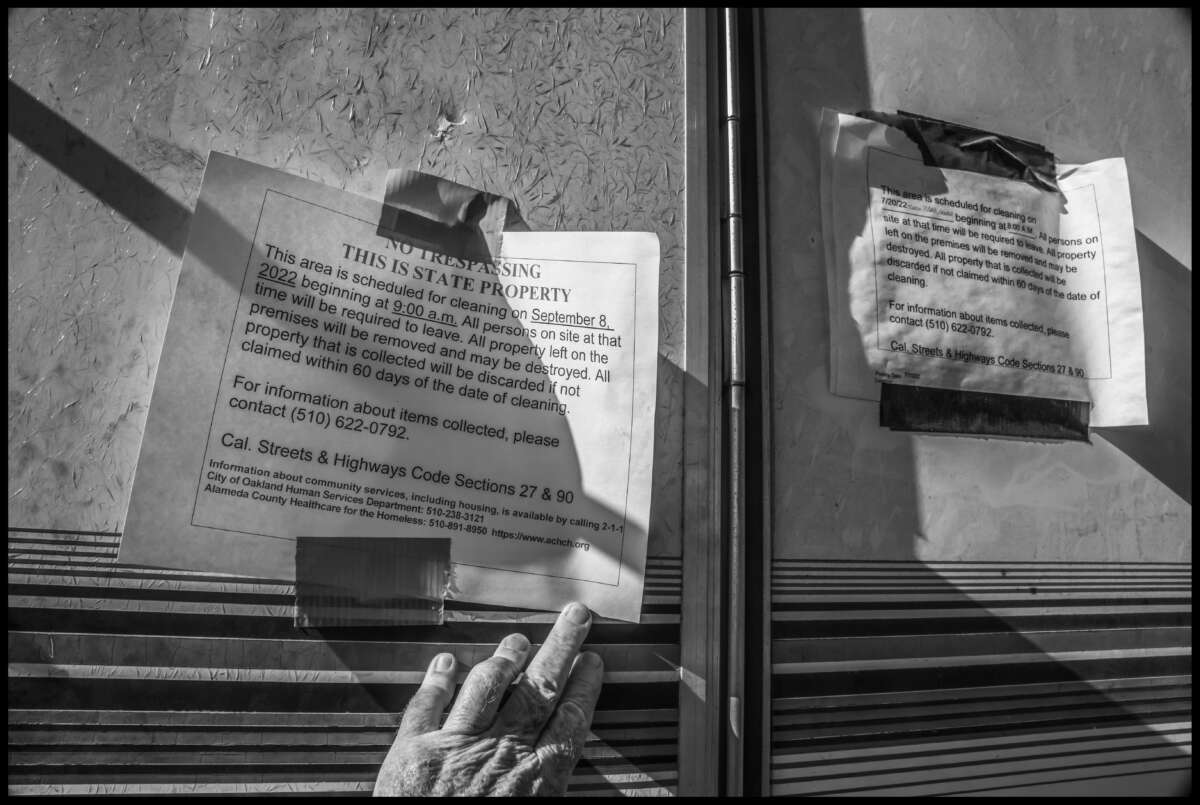

Caltrans, which owns the land under an enormous freeway interchange called the MacArthur Maze, has evicted more than 300 people who had lived there for years. The U.S. Constitution does not recognize a right to housing, Caltrans asserts.

In the end, Federal Judge William Orrick came down on the side of the state. For months, an order he issued in July 2022 had prevented Caltrans from evicting the camp dwellers. Orrick even endured criticism from California Gov. Gavin Newsom, who said the order would “delay Caltrans’ critical work and endanger the public.” But last October, the judge finally accepted the agency’s argument. “I don’t have the authority — because there is no constitutional right to housing — to allow Wood Street to stay on the property of somebody who doesn’t want it,” he admitted.

Early this February the last 60 residents were forced to leave. The strip of land occupied by RVs, tents and informal homes, extending for 25 city blocks, was reduced to a barren expanse of bare dirt and concrete.

The evicted occupiers are part of Oakland’s homeless population, which has increased 24 percent over the last three years. As of early 2022, more than 5,000 people were sleeping on the streets, but the city only has 598 year-around shelter beds, 313 housing structures and 147 RV parking spaces. All are filled.

Nevertheless, Judge Orrick stated in his final removal order, “Though the eviction will inevitably cause hardship for the plaintiffs, that hardship is mitigated by the available shelter beds and the improved weather conditions.” The atmospheric rivers that have dumped flood-level torrents of rain on northern California all winter returned within days of the order.

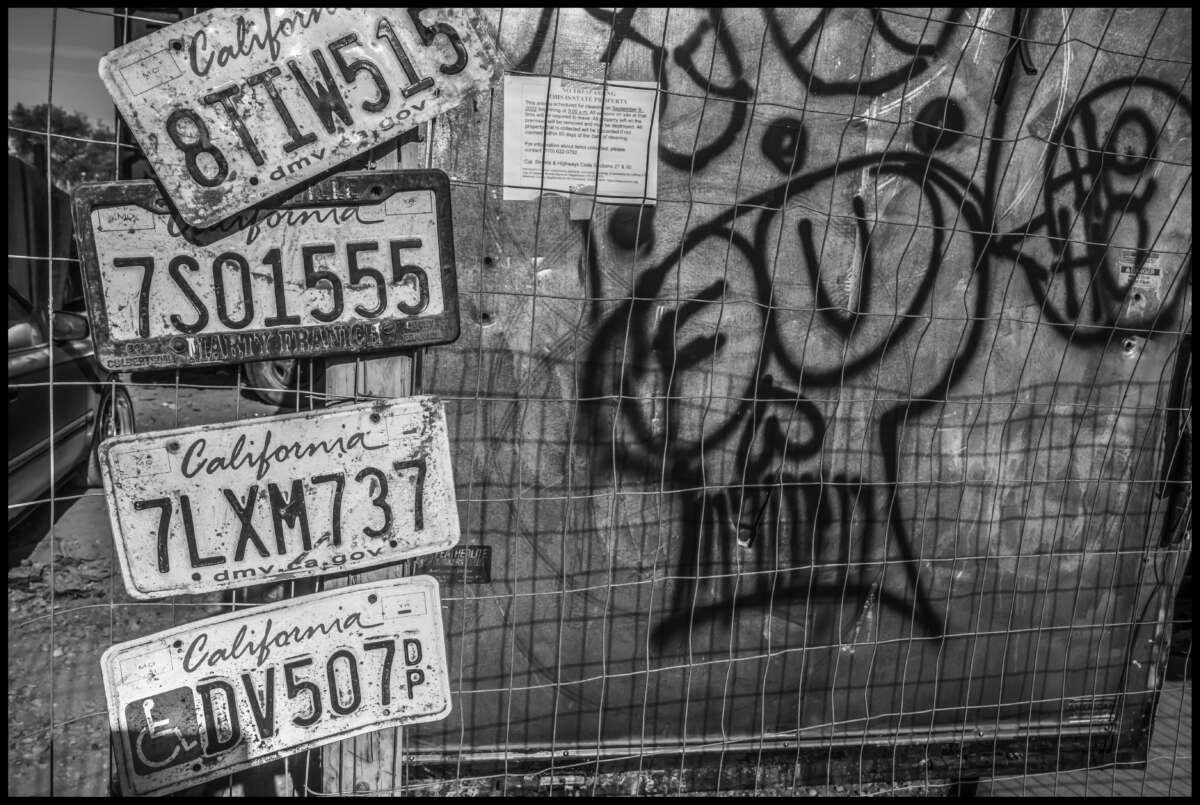

The now-empty camp had a long and storied history. It lined Oakland’s abandoned Wood Street, where houses were cleared in the 1950s to build the freeway maze leading to the Bay Bridge. Seven years ago, as gentrification and the city’s housing crisis grew increasingly acute, displaced people began setting up what became Oakland’s oldest settlement of the unhoused.

Some folks drove RVs and trailers into the huge space next to an old railroad trestle that was used decades ago to move boxcars between the port and the main rail yard. Other home seekers set up tents or other informal housing as the settlement spread. One individual even built a room high up under the trestle beams, 20 feet off the ground. The camp provided safety and peace during the night.

In one small section, residents and supporters erected several small homes and a common area for meetings, entertainment, and other collective activities. They built the structures of cob — a mixture of straw, clay and sand — and Cob on Wood became one of the camp’s nicknames. Other residents call the encampment Wood Street Commons.

In recent years, however, fires on Wood Street became frequent — over 90 in 2021. Last April one man lost his life when a blaze filled his converted bus with smoke and he couldn’t get out. The worst conflagration broke out in July 2022. Propane cylinders used for cooking and heating exploded in flames so hot that vehicles parked under or near the trestle were incinerated. Residents fled.

Firefighters responded to the fires, but there is no hydrant near Wood Street. To reach the informal homes, the bomberos had to stretch hoses over hundreds of feet. Yet Wood Street wasn’t the only camp to suffer blazes. A city audit documented 988 fires in 140 encampments over the two years between 2020 and 2021.

After the July fire Caltrans announced it would evict the residents. Lawyers for the unhoused people convinced Judge Orrick to bar the action, and last summer he seemed sympathetic. When he asked authorities to detail their intentions for providing replacement housing, no agency could come up with a plan.

In 2022 the state gave Oakland a $4.7 million grant to house 50 of the 300 people living on Wood Street, yet the city didn’t use the funds to create alternative housing. Instead, as evictions proceeded, Oakland administrators announced that if the land was not cleared the city would lose funding to subsidize nonprofit developers it claimed were planning to build 170 units of housing on the site — 85 for sale and 85 rentals. While Oakland needs housing desperately, virtually none of the evictees would ever have been able to buy or rent one of the units.

John Janosko, a leader of the effort by residents to block the eviction, pointed to empty land just across the railroad tracks. “We want our community to stay intact,” he explained. “And it wouldn’t be hard for us to move there, especially if the city helped us build small houses and a center and community kitchen where we could have services and meetings to keep ourselves organized.”

The eviction pulled the bones of capitalism into plain sight. The right to property is enshrined in law, and the legal structure of the state will enforce it, even if it leaves people on the street with no place to sleep or live.

When City Council member Carroll Fife proposed that solution in October, however, the city bureaucracy condemned the idea. Moving people would cost too much, and the land might have toxic contaminants, city administrator Ed Reiskin claimed, but refused to apply to the State Department of Toxic Substances for a waiver allowing the site to be used. Fife, a rent strike activist and organizer of Moms for Housing before she was elected, said she was “disgusted.”

So Caltrans created a huge, windswept emptiness where Dustin Denega had built a tipi next to his trailer under the freeway. Not far away, Jake had created a room without a roof between two trestle pilings, complete with sofa, table and work space for an artist. That was gone too.

Denega, an unemployed musician, said that in the four years he had lived on Wood Street, he felt safe and protected from violence that often affects people sleeping on sidewalks. Even in the “tuff shed” cubicles the city provided for the camp dwellers, calling them alternative housing, a man was shot and killed last winter. “That city housing is surrounded by a fence. You can’t have visitors, and it feels like a prison. And it’s not safe,” he said.

In 2018, United Nations Special Rapporteur on Adequate Housing Leilani Farha visited Oakland. She told reporter Darwin BondGraham, “I find there to be a real cruelty in how people are being dealt with here.” In Manila, Jakarta and Mexico City, she observed, homelessness is basically tolerated, while in the U.S., a far wealthier country, being unhoused is criminalized.

Judge Orrick’s finding that there were shelter beds available was not a statement of a real fact, but a requirement for eviction given earlier legal precedents. In 2019, Judge Marsha Lee Berzon on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals held in Martin v. City of Boise that “criminal penalties for sitting, sleeping, or lying outside on public property for homeless individuals who cannot obtain shelter” were unconstitutional. The Eighth Amendment bars cities from punishing anyone “for lacking the means to live out the ‘universal and unavoidable consequences of being human.’”

The court’s decision was no real protection for Wood Street, as the eviction proved, but it did at least acknowledge that being unhoused with no money was a consequence of social conditions, not a crime or personal choice or deficiency.

The eviction pulled the bones of capitalism into plain sight. The right to property is enshrined in law, and the legal structure of the state will enforce it, even if it leaves people on the street with no place to sleep or live. Land is a commodity, to be bought and sold. If the right to live on it comes first, the property of any landowner is in danger. A clean empty space under a freeway, while people sleep in tents on sidewalks, is deemed a preferable alternative to land occupations.

In February the last of the camp residents were removed. As they left, a group of day laborers appeared, taking away belongings and discarding the trash left behind. They were some of Oakland’s lowest-paid workers — Mexican and Central American jornaleros who daily look for work on city sidewalks and parking lots. While they hauled out debris, the unhoused people who would soon be joining them on those sidewalks watched.

In this last twist, according to a foreman on the site, a city contractor had hired a labor broker, who in turn went out to day labor sites to find workers to clean out the camp for the lowest wages possible. To keep those labor costs low, the distasteful work of eviction had been contracted out — one more aspect of municipal neoliberalism, in this liberal city in this progressive state.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate