So what is Free Student Press and why is it relevant to people interested in homseschooling and unschooling?

Homeschooling and unschooling have a lot of appeal to parents who believe children and adolescents deserve more freedom to pursue their own curiosities and creative impulses than conventional schools allow. Free Student Press is based on the same conviction. But instead of seeking to create totally separate alternatives to our public schools, or trying to reform national school policy from the top-down, Free Student Press takes unschooling to school.

What exactly do you mean by that?

FSP starts from the assumption that teenagers don’t need anyone else telling them what to do. What they need are more meaningful opportunities to express themselves, to make sense of their world, and to have an impact on that world. So FSP offers teenagers some very practical tools. The first tool is the knowledge schools typically hide from students about their First Amendment rights to distribute independent student publications at school.

More commonly known as underground newspapers or zines, these publications are produced by students, outside of school, and without using school resources. But then students can bring these publications to school and pass them out to their classmates on school grounds, during school hours. School officials can’t control the content, they can’t punish students for writing things school officials don’t like, and in the overwhelming majority of cases school officials cannot legally prevent students from distributing independent student publications at school.

Within one of these publications, students can create for themselves a unique forum for public dialogue among their peers that is anchored to their experiences as students within their schools, and as young people within their communities. From my experience with these publications, I’ve learned that whatever disagreements students may have with one another, they tend to all want a place to discuss what they care about. So students learn how to manage this forum, because they’re committed to keeping it. They learn how to communicate themselves better, because that’s necessary to change minds and have an impact. They learn about their peers and others’ perspectives, and the situation forces them to contend with others’ arguments. Finally, if school officials attempt to illegally censor a publication – as they often do – students get to learn how to defeat corrupt people in positions of power and authority through grassroots organizing.

Along the way, FSP is there as a resource for the students. We’re not there to tell students what to do, but to respond to their questions and sometimes ask some of our own and offer advice. But it’s up to students whether they want to take that advice. Empowering the students to act for themselves is always the goal.

The entire experience teaches some big lessons that stick with students long after graduation. And the best part of FSP’s approach is that we don’t have to wait until we’ve changed our schools, or until we’ve built better large scale alternatives. Instead, we can turn precisely what’s wrong with our schools into what educators like to call a “teachable moment” – or, more precisely, a whole series of such “moments” that turn disempowering schools into an opportunity for seriously empowering education – the kind of empowering education that not only improves young peoples’ lives, but which also dramatically increases Americans’ capacity to create a freer, more just society.

Let’s back up a bit and talk about students’ legal rights to do this. Are student press rights just a matter of the First Amendment, or of court decisions and/or other legislation?

The First Amendment was a concession early American elites granted in order to get the Constitution ratified. It really didn’t mean anything in practice until mass movements of ordinary people made it mean something – and that’s true for student press rights, too.

Back in the mid 1960s, a group of families in Des Moines, Iowa decided to express their opposition to the Vietnam War by wearing black armbands. Some of their kids wore these armbands to school, for which the children were threatened with violence by school officials and then promptly kicked out of school. The families and allied individuals and organizations fought back, and eventually this resulted in the 1969 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District. The Tinker decision did several things, but most important for FSP it established the right of public high school students to distribute independent student publications at school.

Are there any legal limits placed on what students can do with these publications?

Independent student publishers and journalists are still bound by the same laws as professional journalists, publishers and everybody else when it comes to stuff like libel, invasion of privacy, obscenity, copyright infringement, and so on. But there is only one additional legal restriction that applies to independent student publishers at public schools.

School officials may only attempt to prevent distribution of a student publication if they can show there is a very high probability that the either the contents of the publication or the manner of its distribution would cause a severe disruption of official school proceedings or invade the rights of others. What 46 years of case law following Tinker has made clear is that it is extremely difficult for school officials to meet this standard.

If students have had this right since 1969, why am I just hearing about it now?

It’s not just you. Practically everyone is unaware of this.

For nearly a half century since Tinker, illegal censorship has continued to run rampant in our schools, as documented by groups including the Commission of Inquiry into High School Journalism, the American Civil Liberties Union, and the Student Press Law Center. But the many reported cases of illegal censorship are just the tip of the iceberg. They don’t tell us about all the kids who were lied to about their rights at school, or simply not informed, or students who never reported illegal censorship because they didn’t know it was illegal.

I first got involved in this work during our senior year of high school when three sophomores created a little zine they called Hide and Go Speak. As soon as the students passed out their first issue, they were called down to the principal’s office and told they could not hand out a student publication at school unless they first allowed the principal to edit its contents. Since they had not done so, they were all punished with several after school detentions, and that was the end of Hide and Go Speak.

Now, rights or no rights, I liked what those kids were trying to do. So I went ahead and organized another student publication called Free Head, and it had a tremendously positive and transformative impact on my life. But it wasn’t until a couple years after high school that I learned our principal had simply lied to the creators of Hide and Go Speak and had illegally violated their rights by punishing these kids and banning their zine.

Why did your own high school experience of producing an independent student publication have such a big impact on you?

It taught me that people can work together very productively without any need for a central authority to dictate their course. It also taught me that a forum for public dialogue can cause a community to emerge where none had existed before. Suddenly, students outside of my own social circle, who for years had just been scenery in the hallways to me, were real people with their own thoughts and ideas. And as you might imagine, the intrinsic motivation to communicate myself made me a better writer than years of writing papers on random topics assigned by my teachers.

But Free Head wasn’t just about commentary or indie news reporting, it was about students expressing themselves any way they could on paper. We published poetry and other creative writing, along with visual art – all of which gave budding young artists an opportunity to share their work with a larger audience, often for the first time.

Two aspects of Free Head’s internal structure greatly amplified all of these effects, and also helped protect us from censorship. First, Free Head was public access. We pretty much published whatever students submitted. Second, we governed Free Head through a process of direct democracy. Decisions that affected the magazine as a whole were made democratically at meetings open to any interested student. And with so many students from different cliques having such a voice in the publication, our broad base of support made it harder for administrators to try to shut us down.

Free Student Press supports independent student publishers regardless of whether they choose to adopt a public access format and democratic management, but we do discuss the benefits of these things with students.

And how did Free Head lead to Free Student Press?

After learning about student press rights a couple years after I graduated high school, I partnered with Lisa O’Keefe, a former classmate of ours who also worked on Free Head. And as 19-year-olds, Lisa and I created Free Student Press and launched it in Athens County, Ohio at the invitation of a group of progressive educators at the Institute for Democracy in Education.

What happened when you first put the idea of Free Student Press into practice?

Within three weeks of our first outreach event, the very first group of high school students Lisa and I worked with produced a publication called Lockdown. On page one of their first issue, Lockdown’s creators accurately explained their First Amendment press rights and the Tinker decision. The students even included a supportive quote issued to them from Mike Hiestand, an attorney with the Student Press Law Center, a national student press advocacy group.

And how did the school respond to Lockdown?

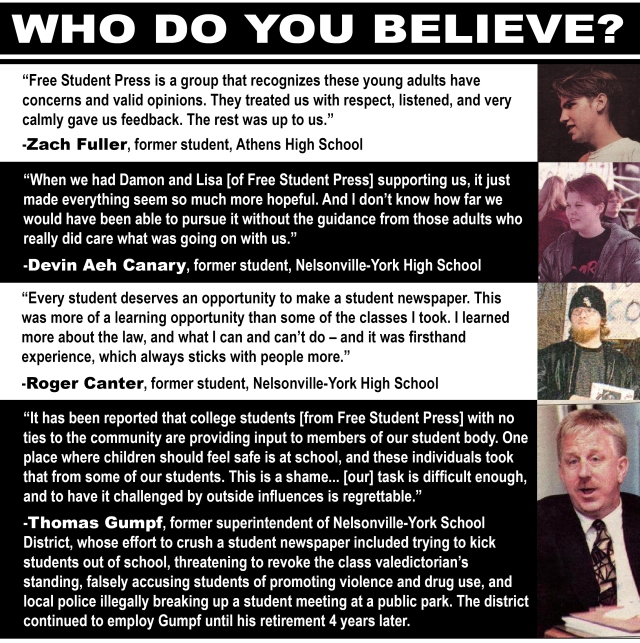

The principal threatened to suspend all of the students involved if “anything like this ever turns up again.” Then he informed the family of Lockdown’s lead publisher, Devin Aeh Canary, that a suspension would likely prevent her from becoming class valedictorian. Later, school authorities falsely accused the students of promoting drugs and violence through their publication, and local police were called upon to illegally break up a meeting about the paper the students were trying to hold at a public park. The superintendent, meanwhile, issued a press release declaring members of FSP irresponsible outside agitators who had made children feel unsafe at school, and he pressured officials at Ohio University (where I was an undergraduate education major) to encourage me to stop FSP’s work.

The conflict was pretty intense, and it lasted for nearly four months. But with FSP’s support the students mobilized so much community support that they completely defeated both their school administration and local police. The students kept publishing Lockdown, and the school’s principal resigned. FSP went on to work with more high school students and independent publications in the years that followed. However, officials at all of the five districts we worked with remained opposed to teaching students their press rights, publicly refusing to include accurate information in their student handbooks after FSP audited the handbooks a few years after the Lockdown controversy.

Why do you think censorship and deception about First Amendment rights are so common in public schools?

It’s a problem of institutional design. Public schools are supposed to be how we teach Americans constitutional rights essential to American democracy, but our schools rarely carry out that mission for the same reason the U.S. isn’t all that democratic. Just as calling a shopping cart an airplane won’t make it fly, the design of our public schools is at odds with the schools’ official mission.

Opposition to student press rights is an inevitable consequence of schools being designed to carry out what Paulo Freire called the banking concept of education. Within the banking concept, students are considered empty containers for a teacher to fill up with deposits of whatever information authorities have deemed valuable.

The first problem with the banking concept is that from the time we’re born, we human beings have our own curiosities and creative impulses. We want to figure out and consciously shape both ourselves and our world. Anyone who has observed young children knows this is what animates them – at least before children are subjected to school. Unfortunately, in the banking concept, these aspects of human nature are the enemy. They’ve got to be beaten down and suppressed so that students can be filled up with whatever is on any given day’s lesson plan.

Within the banking concept, Freire wrote, “the scope of action allowed to the student extends only as far as receiving, filing and storing the deposits… but in the last analysis, it is the people themselves who are filed away…” Similarly, the American philosopher John Dewey asked, “What avail is it to win prescribed amounts of information about geography and history, to win the ability to read and write, if in the process the individual loses his own soul…?”

Now, consider the second problem of the banking concept – it doesn’t work. With reference to a vessel-of-water metaphor for education (essentially the same as Freire’s banking concept), Noam Chomsky likes to point out that we human beings are pretty leaky vessels when it comes to things we don’t care about. Everybody has had the experience of memorizing information for a test, acing the test, and then immediately forgetting what it was we memorized.

So if the banking concept denies the humanity of students and doesn’t succeed in getting students to retain much information, why is it the guiding principle of our schools?

The banking concept isn’t any good when it comes to storing deposits, but it does a great job of filing the people away. At school, particular subject matter comes and goes, but for a dozen years some lessons remain constant: What is important is what the people in charge say is important. You are rewarded to the extent that you please the people in charge. Thus you learn to accept alienated labor as your fate in life. This is extremely beneficial to economic and political elites whose wealth and power is derived from a workforce and citizenry that is apathetic, compliant, atomized and demoralized. And in the U.S., it’s those elites who create public policy and shape our society’s defining institutions.

In Tinker, the Supreme Court declared that authoritarian schools are not compatible with American civil liberties and democratic ideals. As the Court put it, “In our system, state-operated schools may not be enclaves of totalitarianism.” But the reason most school officials have failed to heed the Court’s ruling is that our schools are indeed enclaves of totalitarianism. The banking concept is nothing if not totalitarian. It’s all about controlling thought and behavior from above under the totally false pretext of getting students to retain useful information. And you maintain that system by silencing students’ voices and keeping them powerless. Denying students their legal press rights is just one predictable result – but one that’s obvious and illegal.

What about teachers? Why would they go along with what you’ve claimed about our schools?

A lot of teachers do their best to not go along with it. I could tell you plenty of stories about that, and so could the students I’ve worked with. Teachers have always been among FSP’s biggest supporters and many are backing the current FSP campaign.

But regardless of a public school teacher’s own educational philosophy, it is nearly impossible for a teacher to do anything but the banking concept when the student to teacher ratio is 30 or 40 to 1 and schooling is all about getting kids to memorize what they need to pass high stakes proficiency tests. No Child Left Behind and Race to the Top are some of the most extreme versions of the banking concept ever forced on teachers. Combined with other approaches to de-funding and destroying public education – which, predominantly in communities of color, also include replacing school boards elected by local communities with boards appointed by the city mayor – these reforms are part of the largely bi-partisan, neoliberal agenda to reduce the function of everything in life to a source of corporate profit.

Don’t the American Civil Liberties Union and the Student Press Law Center already do the work of Free Student Press?

No. I love the ACLU and SPLC. FSP always puts students in touch with these groups, and we use some of their educational materials, too. Our work compliments theirs, and their work compliments ours. But neither the ACLU nor the SPLC focuses on independent student publishing as a means of doing ongoing empowering education with students – something I think is absolutely necessary if constitutional press rights are really going to mean something for more than a miniscule fraction of American students. Also, while the ACLU and SPLC primarily fight censorship in the courts and state legislatures, FSP empowers students to fight censorship more directly for themselves through grassroots community organizing. Not only does this impart valuable and lasting skills to students, it often defeats censorship faster – as was the case with Lockdown. That’s important because the courts move slowly, and high school doesn’t last forever.

The internet and social media seem to be such important and revolutionary tools in journalism and the exchange of ideas. What advantage over digital means do you see independent student print media having?

The internet and social media have a hugely positive effect on FSP’s work, but when it comes to independent student publications print is still a necessary starting point.

Facebook is good for staying in touch with pre-existing friends, Twitter is good for sharing pithy remarks with people you may or may not know, and the internet gives you free access to lots of different communication from all over the world – including communication that isn’t controlled by big corporate media conglomerates. But if all these digital media allow teenagers to think more globally, then an independent print medium is still what allows teenagers to act locally.

That’s because independent student print media are anchored to a very specific, and very significant, social context – one that’s not as small as students’ own circle of friends, and one that’s not as big, atomized and impersonal as the world at large. And it’s a context that is physical in nature, not virtual. Most social life, and most social change, still happens in the physical world. And it takes a tangible, physical medium to get into the tangible, physically located social context of teenagers’ shared lives as students at school.

Just the simple act of one student handing a tangible print publication to another student in the real world begins to provide a basis for real-world organizing. Not the kind of “organizing” that simply gets a bunch of people to show up at the same time and place for a big demonstration – as the internet and social media are great for facilitating, but the kind that brings people together in the physical world and enables them to share experiences and ideas, to reflect with one another, and to discuss, debate, decide upon and implement strategic collective actions.

But you said the digital age has its advantages too, right?

Absolutely. With tangible print publications anchored to the physically located social context of a school, the digital age then presents wonderful opportunities to strengthen and expand FSP’s work. First, there’s some evidence that the more young people use social media, the more supportive they are of the First Amendment. Second, the internet and social media can really amplify this work.

Not only can print publications have online versions that can be updated more frequently, be more intertextual via hyperlinks, and allow for even more dialogue via reader comment sections, but the internet can allow creators of student publications at different schools to more easily interact with one another. Just as one publication allows students to interact and support one another across the boundaries of social cliques that separate students within a single school, the internet can enable a network of such publications at different schools that transcends the more substantial barriers of racism and economic inequality that have so greatly segregated American communities.

Do you foresee any difficulty in persuading high school students, who are so entrenched in screen culture, about the virtues of paper publications?

If it’s an obstacle, there have always been bigger ones. Never mind paper being old school – the entire experience FSP offers is so foreign to most American students that most don’t get the abstract concepts at first. Typically, a handful of kids get it immediately, and once they create a publication – particularly a public access one – then the rest of their peers get it and the whole experience blossoms. But it’s finding that initial group of more receptive students that has always been a challenge.

You worked through FSP from 1999 through 2006 with students in Southeast Ohio. Now you’re trying to launch FSP in four Southern states over the next two years, and then take FSP nationwide. Tell me more about that plan.

If the Kickstarter campaign reaches its goal of $25,000 by August 24, then I’ll begin traveling to several college towns in Georgia, Tennessee, North Carolina and South Carolina. In each town, I’ll recruit a team of college student activist-volunteers to assist me with outreach and working with the high school students in their area, just as Lisa and I did when we were undergraduate students. And just as Jalen Hutchinson at the Institute for Democracy in Education mentored Lisa and I in democratic and critical pedagogy, I’ll do the same for FSP’s college student teams, and also teach them about grassroots organizing and participatory democratic organizational models.

From there, I’ll travel from town to town, holding two separate weekly meetings in each town – one with the local FSP team, and one with the local FSP team and the local high school students. In the beginning, I’ll be leading FSP’s work with each group of high school students. But as the skills of the local team members become more advanced, they’ll gradually take over from me, freeing me up to launch FSP in additional towns.

In the meantime, I’ll try to facilitate online networking between the different student publications, and I’ll help the students access the additional resources that the ACLU and SPLC can provide.

Finally, I’ll be chronicling FSP’s work in a book. After this new two-year phase is completed, I’ll get the book published, and use it to try to convince major funders and national organizations to expand FSP all across the country.

What about students at private schools? Does private funding nullify the First Amendment rights of the students.

Yes, it does. Just as we can picket on the sidewalk along Main Street but not at the mall, the First Amendment is all about limiting the power of the government over its citizens, not limiting the power of private corporations over us.

The only quasi-exception I know of is California’s Leonard Law, a state law that provides students at California’s private high schools, colleges and universities with press rights equivalent to the First Amendment rights of public school students.

Of course, progressive private school administrators anywhere can choose to give independent student journalists the same leeway the First Amendment gives students at public schools, but this is totally at the discretion of administrators. Rights, on the other hand, are supposed to mean something whether the people in charge like it or not. That’s part of the reason school privatization threatens student expression and empowerment.

But while private school students don’t have the right to distribute independent publications at their schools, they can contribute to publications produced by public school students and distributed in public schools, and they can attend FSP meetings to learn about all of this and interact with independent student journalists from public schools.

Finally, private school students could try to distribute independent publications simply through the power of their own grassroots organizing and community support, without any legal rights to support them, but this would be extremely difficult – in part because it’s easier for private schools to expel students.

I can see this being something that homeschooled teenagers would enjoy and benefit from being a part of. And I would certainly encourage my son to someday become involved in such projects if he were interested. Do you foresee FSP collaborating with and reaching out to kids who are not educated at school, but who want to learn about their rights and how to organize and engage in a more meaningful dialogue within their communities?

If homeschoolers are looking for a way to engage and learn with their public school peers and to participate in something that gives homeschoolers a stronger voice in their communities, then this is one great way to do it. Homeschooled teenagers can participate in the same way I described private school students participating. But if homeschoolers already have had freer and more empowering experiences outside of conventional schools, then I’d expect public school students would be especially interested to know these homeschoolers, and such relationships would be mutually beneficial.

Ultimately, this is stuff that matters to all of us. Whether we’re teenagers or senior citizens, whether or not we have kids – whether, if we do have kids, we send them to public school, private school, or homeschool them – it’s still our society. What happens at public schools has a huge impact on our society, and therefore affects all of our lives.

How can people support this work?

The Kickstarter campaign needs to reach its goal by August 24, so I encourage everyone who supports this work to donate immediately and to tell all their colleagues, friends and family to do the same. This only works if a lot of us pitch in. But if this campaign succeeds, its impact will be tremendous.

____________________________

Alex Walker is a stay-at-home mother to a three-year-old son. Formerly a figurative artist and portrait painter, Alex is fascinated by sustainable architecture, homeschooling, gardening, and anything involving creative design. She is following her intention of learning more about human rights and progressive values and movements, as well as becoming a practitioner of ecological living. She lives with her son and husband in Littleton, Colorado and is thoroughly enjoying what the state has to offer.

Damon Krane is co-founder and director of Free Student Press. He has worked as a news reporter, opinion columnist, magazine editor, communications director, non-profit director, grassroots organizer and activist, journalism educator, and business manager. Much of his writing is archived at http://damonkrane.com. He is also a visual artist, specializing in black and white pencil portraits of people and pets at http://fineartpetsketches.com He lives with his wife in Atlanta, Georgia.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate

1 Comment

If you care about these issues, you should enjoy the feature length video Free Student Press released earlier this year.

Along with promoting the current Kickstarter campaign, the video discusses FSP’s philosophy with regard to critical pedagogy and social movement scholars Sara Evans and Harry Boyte’s analysis of “free spaces” for empowering education within social movements, such as the consciousness raising groups of Women’s Liberation and the freedom schools of the Civil Rights Movement.

Also, as a case study of FSP’s implementation, the video documents the struggle over the student publication Lockdown, with archival footage shot by the publication’s creators way back when and recent interviews with the former students reflecting on the lasting impact the experience had on their lives.

Here is the link:

https://vimeo.com/user40701466/review/129864695/103ecddb0b