A young woman teaches a class on labor organizing at Highlander Folk School. Source: Wisconsin Historical Society.

If you’ve ever attended a Labor Notes Conference or Troublemakers School or picked up one of our books, you know that everything we do draws on the organizing know-how and creativity of rank-and-file workers.

This style of education is known around the world as “popular education.” In the U.S., it was pioneered at a school tucked away in the hazy Appalachian mountains of East Tennessee.

For decades the Highlander Center has been at the heart of some of our country’s most important social movements. In the 1930s it became the official training center for unions in the Congress of Industrial Organizations, the labor federation that organized millions of factory workers regardless or craft, skill, or race. Union members from across the South attended racially integrated workshops where they shared organizing experiences and honed their skills.

Highlander’s commitment to economic and racial justice also made it an early incubator for the civil rights movement, as when it offered citizenship schools—literacy and leadership workshops that eventually spread throughout the South and prepared tens of thousands of Black people to register to vote.

The Montgomery Bus Boycott and the founding of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee had their start at Highlander, too. It’s where “We Shall Overcome” became a civil rights anthem.

Highlander is still going strong, and in September it will celebrate its 85th anniversary. Chris Brooks interviewed Susan Williams, who has worked as an educator there for 28 years.

Labor Notes: What is popular education, and how does it relate to organizing?

Susan Williams: My experience has been that popular education and organizing are actually one process: people coming together, trying to figure out what to do about a problem, learning more, talking about it, taking action, and then reflecting and trying to figure out what to do again. Sometimes I think that we mystify what is a natural process for people.

Popular education involves passing on skills and content in a collective way; it’s based on the belief that people can do more than they think they can. Good organizing provides people with the ability to learn together and grow. So these processes are connected.

How is this different from the traditional model of education?

Traditional education is about banking: I am an expert, I have banked this information, and I am going to pour it in your head—and you are going to tell me back what I told you.

So when people face problems, their first thought is, “I need to go and find a lawyer!” They think they have to rely on others, who have the right kind of knowledge, to solve their problems. Now we head straight to the Internet and Google. We are not encouraged to think that we have the capacity to change things ourselves.

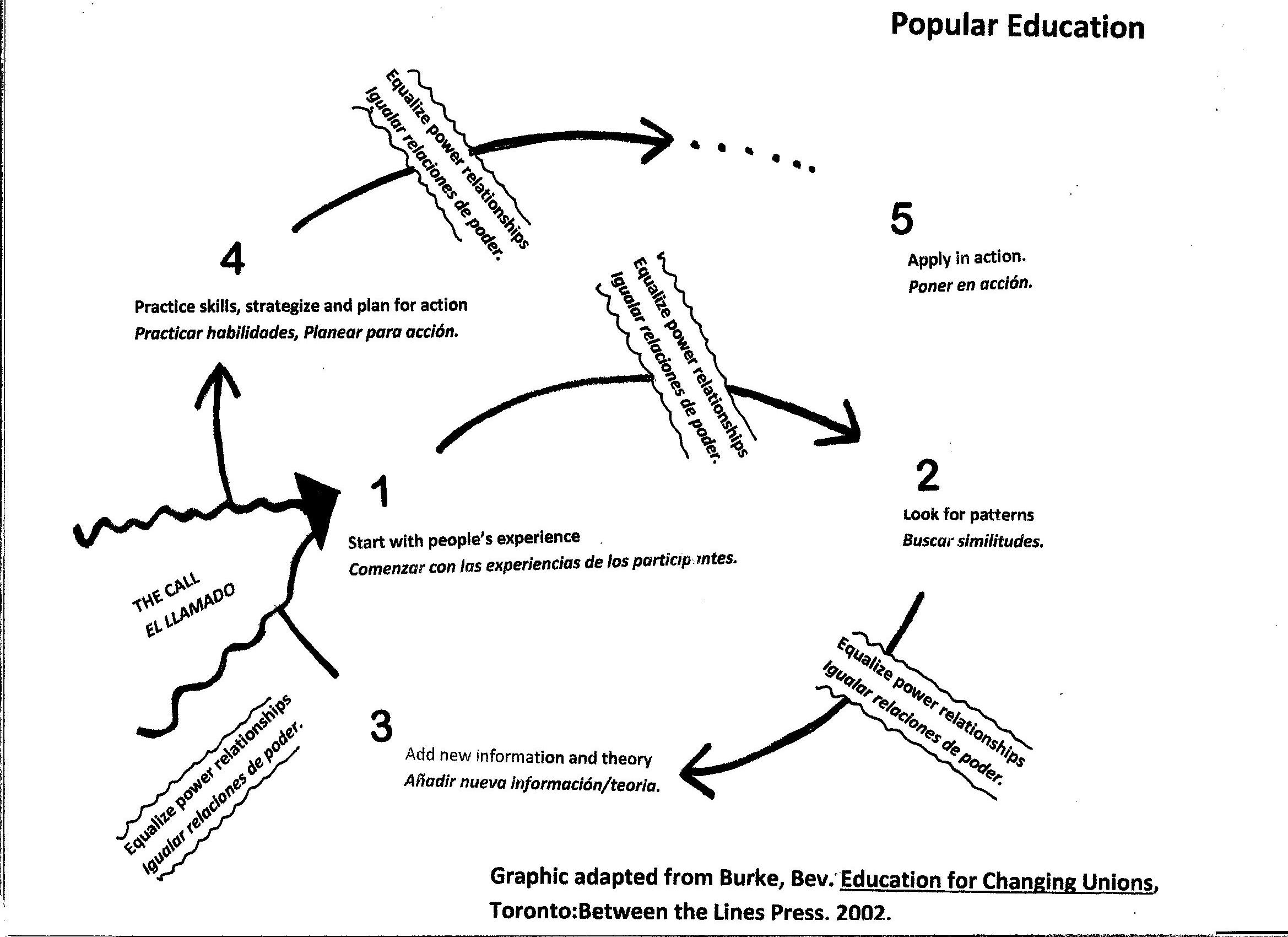

Can you tell me about the popular education spiral and the process it represents?

You are starting with people’s experience, building an analysis and strategy. You’re bringing in more information, which may be coming from within the group or from someone outside it. Then you are thinking about what to do, and you go and try and do it. Then the process starts over again.

Popular-education organizing builds critical thinking and strategy skills across a group of people, not just in one leader. Our idea of an organization is typically leaders and members. A better way of thinking is that we are a group of people with different skills and knowledge. How do we use all those together and make passing knowledge and skills on to others just a natural part of our job?

I think that organizing without thinking about education or our long-haul work is a mistake. And just thinking about education without the point of what we are trying to change is also not useful.

Can you give me an example of how this process plays out?

I came to work at Highlander in the late ’80s. At that time we were working with the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union (ACTWU) to organize a conference around the issue of plant closings. Large textile and apparel factories had been closing all over the South, often in small towns, having major effects on people and communities. So we decided to start a labor-community coalition called the Tennessee Industrial Renewal Network. It lasted from 1989 through 2005.

We started by setting up teams to respond to plant closings, helping people to organize and win back pay if they weren’t given enough legal notice, or to get access to federal training programs.

We soon learned that many of these factories were moving to Mexico, to the maquilas on the border, where they could assemble things cheaper. Then, like now, conservatives were playing up this xenophobic view of Mexicans taking our jobs. We thought it was important to build solidarity with Mexican workers, because we knew that none of these decisions were being made by workers.

So we took women who had worked for companies in Tennessee to meet with the workers in the factories that had been relocated to the Mexican border. While we were there, we started to hear about the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). We learned how this agreement was going to expand the conditions we saw on the border: lowering wages, worsening working conditions, and making more profits for companies.

I had never studied economics and knew nothing about it. None of us were planning to campaign against a trade agreement, but we learned about the issues and realized that there was this larger trend.

When we came back to Tennessee, we ended up creating a slideshow that showed what we had learned about the companies moving factories to exploit workers in both countries, and connected it to the trade agreement that was being negotiated.

The idea that everyone is a teacher and everyone is a learner was powerful, because the workers were seeing this happening. They saw the machines being packed up and sent to Juarez. When they went to the border, they saw the companies they had been working for. They knew what they had been told about who was stealing their jobs, but they saw that it was the companies who were doing this.

Information comes from a lot of places; people have a lot of knowledge. Giving people a chance to look at what they know and analyze it with each other is how we build an analysis of what is happening. We continued doing these cross-border exchanges because it helped people think about trade and the economy—and not just in a U.S.-centric way.

ACTWU did a lot of work in our district. They got their members involved, financed them to go on these trips, and had them provide presentations on their findings to other members. They really invested in their members to be leaders and to provide one another with educational experiences. We were learning all of this together.

The Trump administration is trying to use immigration to divide the working class. What suggestions do you have for having these kinds of hard conversations in our unions, especially if folks are scared to broach the topic?

These issues show up whether or we deal with them or not. That goes for big things like race and immigration and smaller stuff like conflicts between individuals. One way that these issues get dealt with is that organizations crash and burn, or people leave, or Trump gets elected.

I think that hearing the stories of others helps people to understand and connect to the situations that other people face. Like with immigration, one thing that is helpful is to have people think about their own migration histories and why their families moved. This includes migration that does not involve crossing a border, like the migration of families from the South to up North due to racism or because of their economic situation.

The simple act of sharing who we are and what we know is helpful. It lays a base that people can build on. But it is also important to examine the systems at play and the different institutions involved. The broader political debate around immigration in this country is completely unhelpful and doesn’t help people understand anything. If more people had the opportunity to hear the stories of people in Mexico explaining the impact of NAFTA and trade deals, then they could begin to understand.

We aren’t going to get this information from the current political debate. People are going to have to come together and learn from each other. And it can be scary. Race and immigration are very tricky, emotional subjects. That is why thinking about who is in the front of the room is important. People need to see representations of their own communities in our movement’s leadership.

How can union members start incorporating popular education into their own trainings and organizations?

One thing that is really important to think about is what happens before people come together. The spiral begins with something named “the call.” This is the outreach you do. Like in a workplace, you go out and talk to people, you do one-on-ones to find out what people care about and find out what is important to do when people come together. A lot happens ahead of time that can be invisible to many, but will determine the condition of your meeting. How do you make sure people have transportation? How do you deal with multiple languages?

Another important part is actually encouraging people to come, making people feel like their presence is important.

Then when they come, we need to acknowledge and welcome them. It’s important that people share something about who they are. That’s how you start with their experience and build relationships. I hear folks say, “Oh, but that takes so much time.” But if you don’t do it, then you will never build the trust that people need to move together in situations that are hard and scary. In the end, it’s relationships that hold organizations together over time.

Also, education and analysis can happen in a lot of ways. It can happen between small groups of people while they are eating a meal. It can be people writing a song together.

As you listen to stories, you think, “Oh, that is like me! “ or, “Oh, I have that problem too!” Stories help people develop an analysis about what is going on and what they might do.

Then you might bring in someone who might know something important. Like when we worked on plant closings, there was someone who had done a lot of work around the warning signs of plant closings. He came and shared what he knew, and what he knew validated what people had experienced who went through a plant closing, and helped to build on that experience.

A Highlander workshop often brings people from across a movement together, so they can learn not just about the overall situation, but about what people are doing in different places and what works. The point is that when you leave, you have improved your thinking about what you want to do.

Perfection is not really what we are after. Relationship-building, analysis, and action are what we are after.

And this is an ongoing process?

Right. One workshop is not going to solve our problems, any more than mobilizing to one action will. We have to continue the process of bringing people together, putting thoughts in the room, figuring out what to do, going out to do it, and analyzing it. If you have people coming together regularly, like at a union meeting, try to think about what can you do to help people learn something, think collectively about something, and figure out what to do.

It’s also important to think about how to facilitate more people building relationships with one another. If you have an hour-long meeting, can you have some people make and set up food? Can you have people doing all the different jobs? Can you have some time for people to talk with each other? Some people can lead a song.

We shouldn’t limit ourselves and our possibilities by thinking that popular education is a curriculum that you do with people that takes a long time and is only about process, while organizing is all about action and getting things done.

Why is history so important to the popular education work that Highlander does?

Because hope is very important. Why work on something if you think there’s nothing you can do? You don’t need to know for sure you can win, but you do need to know that there’s something you can do. One of the reasons that Highlander is important to people is that it is a reservoir of a history of struggle, in a region where that history is not apparent.

Back to my earlier story: there was a time that we brought a group of workers from Mexico to Tennessee to talk to members of a union in the same industry and to discuss NAFTA. The workers from Mexico were interested in learning how the Tennessee union got organized back in the ’50s, so the union found some of the leaders from that time and had them come and talk about what it took.

The current leaders in the union had not even heard these stories. They were amazing stories, because it was very risky and scary to organize a union in the ’50s in the South.

We need to share this history because it helps inspire us. We realize that we are standing on other people’s shoulders. If it feels like hard work we are doing, we can remember that we aren’t the only people to ever face difficult situations.

We also need to be honest and not romanticize history. Like in the civil rights movement, it’s important for people to remember that it wasn’t all the Beloved Community and it wasn’t all wonderful. There was conflict and friction and hardness and risk and death. Those stories are important, and we don’t share them very much. I think our movement needs to do a better job of sharing our history and helping people to feel connected to it.

1 Comment

“I had never studied economics and knew nothing about it.”

“Traditional education is about banking: I am an expert, I have banked this information, and I am going to pour it in your head—and you are going to tell me back what I told you.”

There is a great deal of value in the above conversation, but it also reflects a general sense of anti-intellectualism that seems especially prevalent in the United States.

To eliminate formal study from a revolutionary process is absurd. All things cannot be learned solely through direct experience.

And the above over-simplified definition of “traditional education” is incorrect, limited and insulting – especially to the millions of professional educators (ranging from those who work for literacy to environmental scientists – and everything in between).

Ask a carpenter about the need to study angles and the value of an apprenticeship, or a nurse about pharmacology. Ask a marine biologist who works with local communities about the need for formal study and training.

This whole notion of separating the mind/body/spirit is as fundamentally flawed whether comes from the right or the left. Human beings have incredible capabilities, both as individuals and collectivities – to diminish any is to diminish all.

All we have to do is to look at what our lives have become to understand that.