You enter through the dark—down a ramp into the underground galleries of the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

There, beneath the bright mall of Washington, sits a small wooden house: the Point of Pines cabin, carried from Edisto Island, South Carolina, and rebuilt plank by plank. The whitewashed boards and low hearth make history unavoidably physical. People once slept here, worked here, prayed here—inside a system designed to erase their humanity. This is what the museum’s “Slavery & Freedom” exhibition does so relentlessly well: it forces truth to stand in front of you.

That truth is exactly what the President says he wants less of.

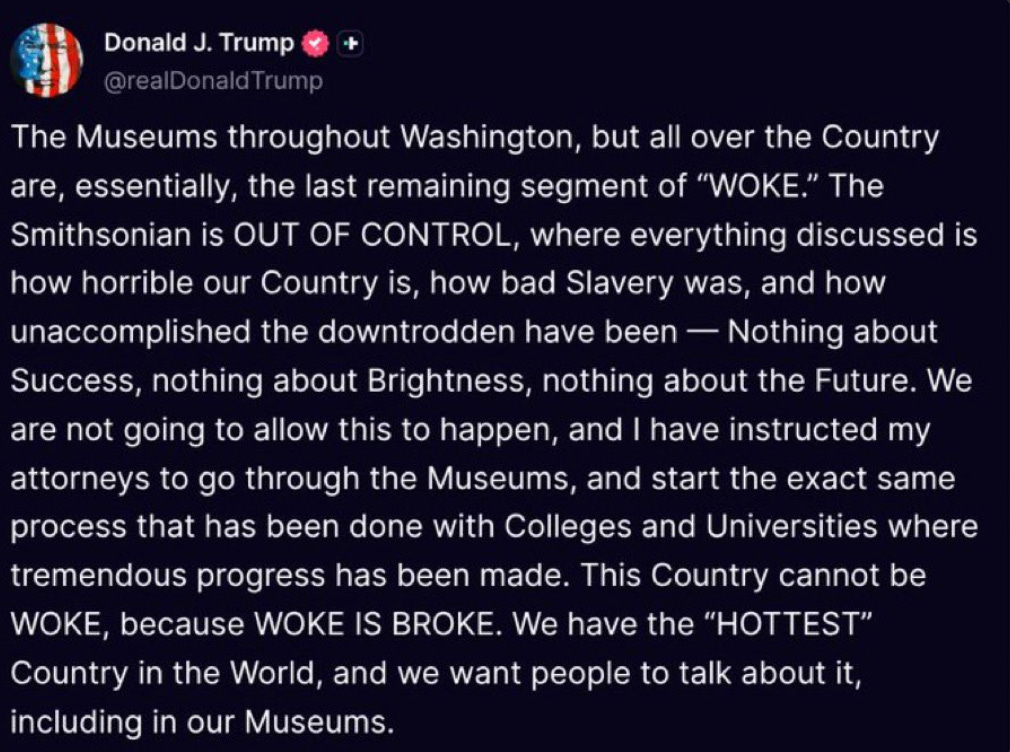

In recent days, he has attacked the Smithsonian Institution as “out of control,” insisting its museums focus too much on “how bad slavery was.” His administration has ordered a 120-day review of eight Smithsonian museums and hinted that funding could be used as leverage to “get the woke out.” The message lands with the subtlety of a hammer: make the story brighter—or else.

This is not a debate about one label or a curatorial tone. It’s an attempt to police memory.

What the Smithsonian actually is

The Smithsonian is not one museum, and it isn’t a partisan project. It’s the world’s largest museum, education, and research complex: 21 museums, the National Zoo, and a network of research centers. Created by Congress in 1846, it receives federal support but is governed independently, with a public mission to collect, conserve, and explain the American story in all its complexity. That mission is supposed to be firewalled from political messaging.

Telling the truth about Black history is not an add-on to that mission—it’s central to it. The galleries at the African American museum trace the forced migration of millions of Africans through the Atlantic slave trade, the violence of bondage, the strategies of resistance, the legal machinery of Jim Crow, the triumphs and setbacks of Reconstruction and the civil-rights movement, and the unfinished struggle for equality today. None of this diminishes the United States. It completes it.

Unless you’re Trump, it demeans it, and he wants to wash that from America’s memory.

The new pressure campaign

This year, the White House issued an order to “restore” American history in federal spaces, casting the Smithsonian as captive to “ideologically driven” narratives. On August 12, a formal letter instructed a 120-day internal review of eight museums—including the African American museum, the American History Museum, the National Portrait Gallery, the American Indian museum, and others—with an eye to “corrections.” Days later, the President escalated his public attacks, claiming the institutions talk too much about national failings, especially slavery.

Even if no curator ever receives a direct edit from a political appointee, that drumbeat creates a chilling effect. Museum professionals across the country hear it clearly: steer away from hard truths, or risk becoming the next target.

The impeachment label became a warning flare

At the National Museum of American History, a wall label referencing President Trump’s two impeachments was removed during a summer refresh of the long-running “American Presidency” gallery. The museum said the label was a temporary 2021 insert and that an updated impeachment section would return as part of broader maintenance on a gallery that first opened in 2008. That explanation may be entirely true.

But timing matters. When a President is publicly threatening your institution while demanding “brighter” narratives, even routine curatorial changes look like capitulations. That’s how chilling effects work: they make scholars second-guess facts that should be straightforward.

Why honest history is non-negotiable

Author and Equal Justice Initiative founder Bryan Stevenson has long argued that a country cannot heal what it refuses to name. Museums aren’t neutral warehouses; they are classrooms for a nation still learning how to live with its past. If we sand down the brutality of slavery—or minimize democratic guardrails like impeachment—we don’t create unity. We create amnesia. And amnesia is fertile ground for abuse of power.

Smithsonian Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch III has said the job of a historian is to help people remember what they need to remember. That includes the difficult parts: the Middle Passage, plantation economies, racial terror, redlining and voter suppression, and the long arc of resistance—because those realities shaped law, wealth, neighborhoods, and opportunity. They’re not “negative”; they’re causal.

Leaders in the Congressional Black Caucus have been blunt: Black history is American history. Efforts to whitewash it are not about patriotism; they’re about control.

What changed—and when

- March: The President signs an order directing federal cultural institutions to emphasize “uplifting” narratives and rails against “race-centered” history.

- Late July: The American History Museum removes the impeachment label during a gallery refresh and says an updated section covering all impeachments is forthcoming.

- August 12: The White House sends a letter launching a 120-day review of eight Smithsonian museums, signaling possible changes to exhibit language and approach.

- August 19–20: The President intensifies public attacks on the Smithsonian and its slavery exhibits, and hints that federal funding may be used as leverage.

This is a sequence, not a series of isolated events. It’s a strategy. The Evilness behind this isn’t a bug. It’s a feature and the purpose. To whitewash hundreds of years of racist violence against black people while Trump’s ICE goons threaten them in their homes, minus any fundamental human rights.

Trump’s “Golden Age” for America comes with turning back the clock and denying hundreds of years of black history because Trump’s “Golden Age” means the white man gets to decide what your past, present and future looks like.

The stakes—for classrooms, communities, and democracy

- For students: Field trips to the Smithsonian aren’t just photo ops. They’re where young people learn to map cause to effect—to see how policy, power, and people collide. Diluting the record blurs that map.

- For communities: Museums are among the few civic spaces where we encounter evidence together. When political actors dictate the labels on the walls, they don’t just edit text. They shrink the public’s window into proof.

- For democracy: A nation that can’t describe its past accurately cannot recognize when it is repeating it. That’s why authoritarians attack archives, historians, and journalists first: control the narrative, and you control the future.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate