As a dangerous factionalism metastasizes throughout the United States, fracturing society and poisoning the atmosphere, our government is becoming increasingly hamstrung and ineffectual – a predicament each political party blames its rival for, while stray fingers point at a host of other putative causes. But no one is pointing at the quietly hulking elephant in the room: the fact that, due to the seismic technological advances that have taken place since the Constitution was written, the process by which we choose our leaders is breaking down before our eyes.

Consider that, by removing nearly all gatekeepers from the equation, the Internet has created a situation in which one of the public’s main information sources – which, in the past, were limited for the most part to rigorously overseen books, periodicals and broadcasts – is at times an anything-goes free-for-all where lies, misinformation and even unhinged ravings share equal billing with well-founded facts and guidance. This not only amplifies fringe beliefs; it also makes it easier to manipulate people and harder to distinguish true from false. And it’s been especially disruptive in the field of politics, where it compounds effects that were set in motion decades earlier by the rise of television, whose own collateral damage includes reinforcing a taste for appearance at the expense of substance, and fueling a celebrity-oriented culture in which candidates who are already stars have a decided advantage. The net result of all of this is a form of government that might as well be called “manipulocracy.”

How did we get into such a fix? The answer may lie in our biological heritage. According to experts, the human brain evolved to cope with the sudden, dramatic dangers – as signaled by the roar of a predator, the smell of smoke from a wildfire, the quick motion of an enemy ambush – that constituted the main survival threats in prehistoric times. The result is that we’re neurologically prewired to register the kinds of “loud” stimuli that seldom indicate a major threat today, and to ignore those of a subtler kind, such as harmful but gradual changes in our surroundings – or a hallowed institution’s slow-motion slide toward obsolescence.

If the past 247 years were compressed into a 30-second time-lapse video, it would highlight how much our country has changed during that span, underscoring why our electoral process might need updating to keep pace. When the Thirteen Colonies declared their independence from Britain in 1776, their combined population was less than three million – mostly White Christians of English stock. Much of the North American continent was wilderness, travel by land was a plodding adventure, and communication was mainly in person or on paper. Today, the U.S. population exceeds 330 million and includes virtually every race and creed. Our frontiers have shifted to outer space and cyberspace, and technology has drastically altered life and landscape.

Yet, while the American ship of state has evolved from a wind-powered schooner into a high-tech ocean liner, its steering mechanism remains the equivalent of a simple wooden rudder in one key respect – and the result is clearly not what the country’s founders had in mind. Although today’s technology has improved our lives in countless ways, it plays havoc with the electoral process – and not just by making it easier to spread misinformation and stacking the odds in favor of candidates who are already stars. The medium of television practically canonizes anyone who happens to be telegenic, and it also creates an illusion of intimacy that predisposes us toward candidates who project an amiable image – both attributes being completely irrelevant to a candidate’s fitness for office. In addition, the combined forces of TV, radio and social media have reduced many political messages to short sound bites (which oversimplifies complex issues and narrows voters’ perspectives), while supercharging such divisive tools as attack ads (which amps up the level of manipulation and has helped create a political climate so adversarial that it obscures common goals and hampers the ability to govern).

On top of all this, election campaigns have become so expensive that a candidate’s actual qualifications can be overshadowed by his or her access to money, thus tipping the scales in favor of the well-to-do and the well-connected. In addition, relatively short terms of office engender an overriding concern for re-election on the part of the officials, which colors their decisions and, by encouraging short-term thinking, works against solving long-term problems that our Founding Fathers never imagined but that include the most-serious ones we face today. What’s more, finding real solutions to those problems is so difficult and urgent a task as to leave little time for image-polishing and campaigning for re-election.

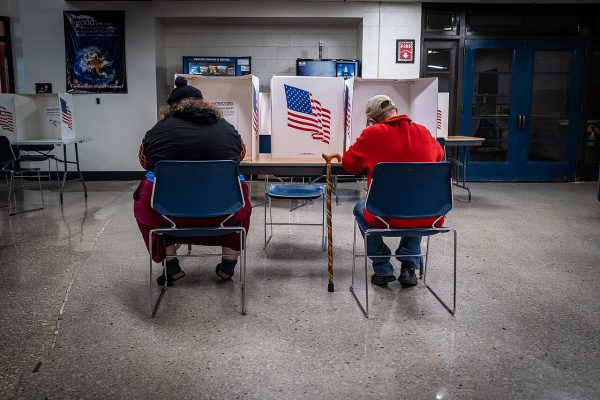

Then there’s the matter of the voters. Our country’s founders were very clear in cautioning that the electoral process would be effective only if the voters were well-informed. Yet surveys show the American public falling decidedly short of that when it comes to local, national and world affairs – understandably, since those affairs are far more complicated than they were when the country was founded, and require considerable effort just to keep up with. What’s more, to fulfill all voting obligations in a diligent manner, a U.S. citizen might need to study the background and past performance of dozens of candidates at the national, state and local levels – to say nothing of all of the pertinent issues. Because not everyone has the time, inclination and wherewithal to do this, the situation ends up overwhelming many voters, resulting in lower turnout at the polls (which makes for a less-representative government), and in votes that are based on ignorance and misconception (which is not exactly what our country’s founders had in mind). The voting process is muddied even further by the fact that, with the help of electronic media, politics has become a major source of entertainment, which at times seems to eclipse its intended function.

What this all adds up to is a situation that would have appalled the Founding Fathers, who came up with the electoral process as a practical solution suited to the conditions of their day, and not as a holy totem. So sacrosanct has it become, however, that the thought of altering it is likely to strike many people as heretical. But history shows that whatever fails to adapt eventually dies out; and since modern technology has distorted the electoral process into something that’s no longer in keeping with its intended function, the question becomes: How, then, should we choose our leaders?

One way could be by random selection. At first glance, that might seem radical and even a bit crazy – not to mention, well … random. But random selection is precisely the way many officials were chosen in ancient Greece, democracy’s birthplace. Randomly selecting a nation’s leaders from among its citizenry comes closer to the literal definition of democracy – which is “rule by the people” – than does any other method of choosing them. Not only does it avoid the above-mentioned factors that have blunted the effectiveness of today’s electoral process; it also prevents the power-hungry and the self-seeking – as well as those who use charm and deceit to mask dangerous shortcomings – from pursuing office. And although the institution of voting has acquired an aura of sanctity befitting a sacred religious rite, our country’s founders weren’t exactly “pious” in that regard, with not all of them keen on allowing the people to elect government leaders. For example, Roger Sherman, Connecticut’s delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1787, vigorously protested against the idea, commenting that the citizens “lack information and are constantly liable to be misled.”

While random selection would be a radical departure from how we’re accustomed to choosing our leaders, it would ensure that, over the long run, they were as demographically and politically representative of the country as reasonably possible – and it would also do away with the controversial Electoral College and put longstanding campaign-finance concerns to rest. Random selection could be carried out easily enough by random-number generators or any other suitable method that was audited to prevent tampering. Leaders could be randomly selected from among all interested citizens who were between the ages of, say, 25 and 70, and who passed a confidential screening test to ensure basic mental health, sufficient cognitive ability and a level of general knowledge at least equivalent to that of the average college graduate. Among those selected, background checks and psychological evaluations – monitored to prevent their misuse – could eliminate anyone who showed indications of unsuitability.

An aside about the presidency: Although we reflexively conceive of the president as being an individual, the tradition of entrusting only one person with our nation’s highest leadership has less to do with the requirements of the position than with sentimentality and force of habit. And in fact, it turns out that our country’s founders were far from unanimous about creating a single-person presidency and debated it hotly, with some of them – including Ben Franklin – proposing an executive council instead. In today’s highly polarized environment, an executive council would be especially fitting, because it would act as a moderating influence, reducing the likelihood of extreme positions and guarding against the possibility of the country getting a “rogue” president – and the likelihood that the constant onslaught of media-magnified attention from millions of people, all focused on one single president, would affect his or her judgment and performance. Such a council could consist of, say, five people – a size small enough to take quick action in urgent situations but large enough to minimize the likelihood of aberrant decisions. To ensure that its members had relevant experience, they could be selected at random from among the randomly selected members of the Senate and House of Representatives, with the vice president selected by the same process – and with all of them serving single terms of office lasting, say, eight years. A similar schema could be used by state and local governments.

Although the mere thought of changing how we choose our leaders is enough to raise hackles from coast to coast, the updates suggested here – “random” though some of them might seem – would do much to smooth out the age wrinkles that nowadays line Uncle Sam’s face, and might even get him to smile. Government would be put, quite literally, back into the hands of the people and would be protected against being dominated by factions of any kind. Our nation’s leadership would no longer be determined by a process that was susceptible to manipulation, misinformation and the cult of personality. Leaders could make the best possible decisions on our behalf, without being influenced by re-election concerns. Removing the party system from the selection process would help depolarize the country and encourage a spirit of unity and cooperation. And the enormous sums of money currently spent on election campaigns would be freed up for better use. The result would be a government that was not only more in keeping with the intentions of our country’s founders, but also more effective and more democratic than what we have now – closer to being truly “of the people, by the people, for the people.”

Wishful thinking, of course. But unless the present system is somehow brought up-to-date with the realities of the 21st century, our government’s effectiveness will continue to erode, and we as a nation will have far less control over our destiny in the years to come than we had once upon a hopeful, giddy and revolutionary time.

Dan Sperling is the author of three books as well as numerous articles and reviews that have appeared in such publications as the Washington Post, Forbes, USA Today and Rolling Stone.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate