Michael Parenti died today at 92, peacefully, surrounded by family.

His son Christian reflected: “Now he is in what he used to refer to as ‘the great lecture hall in the sky.’”

For millions of us who never set foot in his classroom, because by the time we found him, he’d been exiled from the classroom, this hits like the loss of a teacher we never got to thank. The one who explained what no one else would. The one who made it make sense, for me anyway.

The Blacklisting

The story of how Michael Parenti became Michael Parenti is the story of what happens when you refuse to play the game. A game many of us now know. Well, he was the beta tester.

In May 1970, Parenti was an associate professor at the University of Illinois. The National Guard had just killed four students at Kent State. The Vietnam War was grinding on. Parenti joined a campus protest. State troopers beat him severely with clubs and threw him in a cell for two days.

He was charged with aggravated battery of a state trooper, along with disorderly conduct and resisting arrest. Despite multiple witnesses offering exonerating testimony, the judge found him guilty on all counts. The conviction was a message.

That fall, he started a new job at the University of Vermont. His department voted unanimously to renew his contract. It didn’t matter. The board of trustees, under pressure from conservative state legislators, overruled the faculty and let his contract expire, citing “unprofessional conduct.”

He never held a permanent academic position again. He later learned from sympathetic contacts at the schools he applied to that he was being systematically rejected for his political views and activism. The academy had spoken: Michael Parenti was too dangerous to teach.

So he did something else. He took his classroom to the people.

The Work

What followed was one of the most remarkable intellectual careers of the twentieth century, conducted almost entirely outside the institutions that credential “serious” thought.

Over twenty books. Hundreds of lectures at universities, community centers, union halls, churches, anywhere that would have him. Translations into twenty languages. A body of work that reached further beyond the ivory tower than almost any political scientist of his generation, precisely because the tower had expelled him.

The titles alone form a curriculum in understanding power:

“Democracy for the Few” (1974) — His textbook on American politics, now in its ninth edition, which generations of students have encountered as the antidote to their sanitized civics classes. It asked a simple question: If this is a democracy, why do the same interests keep winning?

“Inventing Reality: The Politics of News Media” (1986) — Published two years before Chomsky and Herman’s “Manufacturing Consent,” it laid out how the press serves power while claiming to check it. Parenti understood that the bias wasn’t in what journalists believed but in what they were structurally permitted to say.

“Blackshirts and Reds: Rational Fascism and the Overthrow of Communism” (1997) — A book that infuriated nearly everyone. It examined fascism and communism not as equivalent totalitarianisms but as opposites—one the weapon of capital, the other its target. He asked uncomfortable questions about what was actually lost when the Soviet Union fell, and who benefited from its destruction.

“The Assassination of Julius Caesar: A People’s History of Ancient Rome” (2003) — Even when he wrote about antiquity, he was writing about now. His Caesar book examined how Roman historians, themselves aristocrats, framed the murder of a popular reformer as a noble act of tyrannicide. The same dynamics, he showed, shape how we tell stories about power today.

“Against Empire” (1995) and “The Face of Imperialism” (2011) — The bookends of his work on American foreign policy, documenting how the machinery of intervention operates: the economic interests it serves, the lies that lubricate it, the bodies it leaves behind.

And then there was the book that changed everything for me.

To Kill a Nation

I came to “To Kill a Nation: The Attack on Yugoslavia” not knowing what I would find.

I had absorbed, like most Westerners, the approved story of the Balkan wars: ancient ethnic hatreds, genocide, NATO as reluctant savior. Milošević as yet another new Hitler. The bombing as tragic but necessary. But unlike most Westerners, I was uncomfortable with the accepted narrative. There was something off, and I couldn’t quite put my finger on it.

Parenti dismantled this story with surgical precision.

What I found in those pages was a meticulous autopsy of how the West deliberately destroyed a multi-ethnic socialist federation. How Yugoslavia was targeted not because of Milošević’s “brutality”—the U.S. had coddled far worse—but because it represented an alternative. A country with public ownership, worker self-management, universal healthcare and education, relative ethnic harmony. An obstruction to the expansion of free-market capitalism into Eastern Europe.

He documented how Western financial institutions demanded privatization and austerity, how those policies generated the economic chaos that nationalists exploited, how Germany and the U.S. encouraged secessionist movements, how the media manufactured consent for intervention by repeating unverified atrocity claims while ignoring NATO’s own atrocities. The Račak massacre. The Markale marketplace bombings. Stories that fell apart under scrutiny but had already served their purpose.

He showed how “humanitarian intervention” became the velvet glove over the iron fist, a doctrine that would be deployed again in Iraq, in Libya, in Syria, wherever sovereign states obstructed Western capital or strategic interests.

That book cost Parenti his friendship with Bernie Sanders, who had supported the NATO bombing. He wrote it anyway.

That was the man. He didn’t soften his analysis to keep friends or stay respectable. He followed the evidence into uncomfortable places and reported what he found, knowing it would cost him.

And he was right. About Yugoslavia. About Iraq. About Libya. About the pattern. Once you saw it, you couldn’t unsee it. Every new war, you recognized the playbook: the atrocity propaganda, the demonized leader, the “reluctant” intervention, the ruined country left behind, the corporations moving in to pick over the bones.

“To Kill a Nation” armed me to see through the fog of the next war, and the next, and the next.

The Lecturer

If Parenti had only written books, he would be remembered as an important dissident scholar. But the books were only half of it.

His lectures became a phenomenon before “viral” was a word. Long before podcasts, before YouTube algorithms, grainy recordings of Parenti talks circulated like samizdat through the early internet, uploaded by anonymous devotees, shared on forums, burned onto CDs and passed hand to hand.

“Conspiracy and Class Power.” “Imperialism 101.” “The Darker Myths of Empire.” “Capitalism and the Yellow Parrot.” “The Sword and the Dollar.”

And if you know, you know: Yellow Parenti. The infamous upload where the color balance was so broken he looked jaundiced. It didn’t matter. People watched it anyway, thousands of times, maybe millions by now, because the man could be any color and you’d still hang on every word. In fact, I think it made it better.

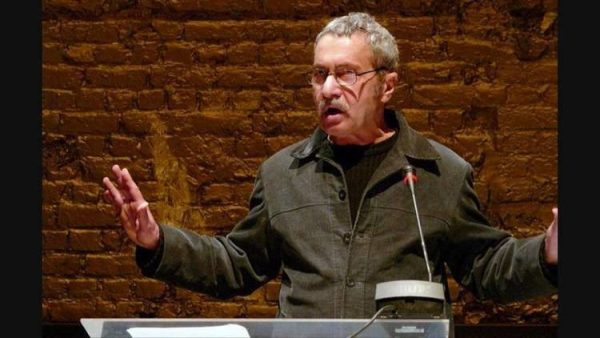

These weren’t dry academic presentations. Parenti was a performer. His waving Italian hands reminded me of my crazy uncles from the “old country.” He was funny, wickedly, disarmingly funny. He told stories. He did voices. He built to punchlines and then slid the knife in while you were still laughing. He had the timing of a stand-up comic and the rigor of a scholar, and he understood something most leftist intellectuals never grasp: you don’t win hearts with jargon. You win them with clarity, with evidence, with the courage to say plainly what others hedge.

A whole generation was radicalized by stumbling onto a Parenti lecture at 2 AM, searching for something they couldn’t name, and finding a man who named it for them.

“The worst thing you can do to ruling interests is to tell the truth about them.”

The Legacy

The establishment ignored him when it could and dismissed him when it couldn’t. He was never invited onto the Sunday shows. He wasn’t cited in the prestige journals. The respectable left kept him at arm’s length, embarrassed by his refusal to condemn the Official Enemies with sufficient enthusiasm, by his insistence on asking who benefits from the stories we’re told.

But his books kept selling. His lectures kept circulating. His ideas kept spreading through the cracks in the official story.

Today, as I write this, American warships are steaming toward the Persian Gulf. Bombs are falling on Lebanon. The patterns Parenti documented are playing out in real time, the same propaganda techniques, the same humanitarian alibis, the same imperial machinery grinding forward.

He would not be surprised. He spent his life teaching us to expect exactly this.

What he gave us was not hope in the sentimental sense. He gave us something more useful: clarity. The tools to see the system as it operates, not as it describes itself. The understanding that none of this is natural or inevitable, that it is built and maintained by specific interests for specific reasons, and that what is built can be dismantled.

He was a street kid from East Harlem who got a Yale PhD and then got exiled for refusing to shut up. He ran for Congress in Vermont as a third-party socialist and got seven percent of the vote. He served for twelve years as a judge for Project Censored. He wrote about ancient Rome and modern empire, about media manipulation and FBI repression, about fascism and the destruction of socialism. He never stopped. He never softened. He never apologized.

He was 92 years old. He died peacefully, surrounded by people who loved him.

The lecture hall was wherever he stood. Now it’s wherever we carry what he taught us.

Rest in power, Dr. Parenti. The contradictions sharpen. The empire stumbles. And your voice, that voice, tough and hilarious and relentless, it is still echoing through every basement bookshop, every late-night video spiral, every kid who just figured out the game is rigged and wants to know how deep it goes.

The great lecture hall in the sky just got its best professor.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate