In a letter to Richard Nixon dated January 16, 1970, his domestic advisor Daniel Patrick Moynihan wrote the following regarding the White House approach to the situation of Black people in the United States: “The time may have come when the issue of race could benefit from a period of “benign neglect.” The subject has been too much talked about. The forum has been too much taken over to hysterics, paranoids, and boodlers on all sides.” The letter continued, maintaining its patronizing and racist tone throughout, blaming the Black Panther Party and others (boodlers!) for the fact that white US residents even cared about African-Americans. This letter and the term “Benign Neglect” became a symbol of the short-lived attempts by liberals to address the racially based inequality in the United States.

As the years progressed, that benign neglect morphed into an intentionally malignant form of neglect, turning neighborhoods into food deserts and drug marketplaces, destroying job and education programs, and ultimately forcing African-American residents from their homes to make way for gentrification. Those neighborhoods that didn’t get gentrified often turned into shells of their former selves. In other words, no shops, rundown schools, neglected infrastructure and no health care facilities. Funding was denied and families were destroyed. The government’s rejection of responsibility—both historically and in real-time—continues to this day. Indeed, in the current phase of US history, where greed and white supremacy are celebrated and signed into law, that rejection has become both aggressive and expected.

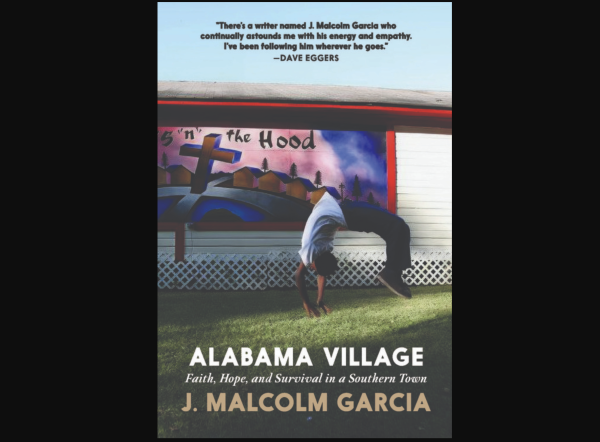

Into this reality steps author J. Malcom Garcia. Garcia’s books focus on those whose lives mean little to nothing among the rulers and their wealthy co-conspirators. Refugees, immigrants, those in foreign countries bearing the brunt of US imperial policies, the homeless; all those cast by the wayside in the march of US capital towards total domination and ultimately total destruction. Garcia tells the stories of these folks with compassion and honesty; his writing is textured and engrossing, emotional yet rational. The narratives of his subjects, his characters if you will, are presented with an honesty one will rarely find any more in a mainstream media source. That in itself is one fine reason to read his work.

Alabama Village: Faith, Hope, and Survival in a Southern Town is Garcia’s newest title. It is the story of Prichard, Alabama, a town north of Mobile, Alabama in that city’s outer suburbs. Although the town wasn’t officially settled until after the US Civil War, its story begins with the arrival of the Clotilda, an illegal slave ship. The ship docked in Mobile Bay in July 1860. On board were 110 Africans purchased in on behalf of Mobile shipbuilders and merchants. After unloading the humans onboard, the ship was burned and sunk to escape discovery. The Africans were taken upriver and distributed among the investors in the voyage. After the war, some of the Africans returned there, developing Africatown as their own community. By the beginning of World War One, Africatown was called Prichard and was becoming industrialized. After the war it became a major shipbuilding site, in essence a company town. By the early 1970s, after the end of legal apartheid, school desegregation and white flight, Prichard was still doing pretty well economically. However, when two major paper mills shut down in the 1980s, Prichard suffered dramatically. Its population dwindled and in 1999, the city declared bankruptcy.

Fast forward to 2020. J. Malcolm Garcia gets a call from a friend who tells him about a PBS program he saw about Prichard, Alabama. The focus of the program was the incessant street violence; violence that the program compared to Syria, which had been in the throes of a civil war for several years. Garcia investigated a bit further and decided to write Alabama Village.

The primary protagonists in the book are two ministers known as Mr. John and Miz Dolores. They call their church Light of the Village and their ministry is one that takes care of the people in the village without prejudice or conditions. It’s not that they don’t attempt to proselytize, it’s more that there are human needs that must be addressed first. Then there’s the concept that deeds speak louder than words, a concept not too popular among certain US churches that put their pastor’s wants before anything else, earthly and otherwise. The picture Garcia paints with his words is one that is emotionally complex and a damning indictment of how the United States treats its poorest and most disenfranchised residents. The only common occurrence in the lives of the people he portrays is gun violence. There’s a fellow whose given name is Corey but who goes by the moniker Big Man, a nickname a relative gave him when he was a kid big for his age. He’s a drug dealer who knows the church and its ministers; he participated in its activities as a youngster and keeps communications open with John and Delores. He even invites them to go out to dinner with him paying only to be shot and killed before the lunch can take place. A young woman known for her fighting abilities as a teenager turns a page and decides to go back to school and provide for her children. The ministers understand how broken the lives and the community they are working with are. They don’t condemn and they don’t place blame. The second truth makes them better people than me, for I place the blame directly on neglect—benign and otherwise—that is intentional and racist at its core.

Delores and John are not heroes, nor are the people they minister to villains. The fact of their Christian faith has little to do with their religious beliefs and much to do with their faith in humanity’s essential goodness. Unfortunately, their work cannot and will not effect any fundamental changes in the system they are a part of. Every individual success among the people they minister too is tempered by the ever-cascading failures of that system whose wounds they try to bind. The town he describes, like so many others in today’s USA, is a place where hope, no matter how audacious, is unlikely to find a permanent home. J. Malcolm Garcia’s writing is sympathetic, persuasive and graceful. His narrative places his protagonists’ humanity front and center, extracting the ultimate complexity of human life from the tale of each human portrayed.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate