As I write, French technocrats are demanding

€44bn in tax rises and spending cuts for 2026 that include scrapping two days of national holiday, freezing rises to pensions and social welfare benefits for a year, and requiring a “solidarity contribution”, as yet undefined, from the wealthy.

They claim no doubt that policies are ’neutral’ and unrelated to questions of political power. French political parties are being told to put up with austerity – and to shut up. If the policies fail, or the government collapses then elected politicians will be blamed for not having forced the policy through.

The only beneficiaries of these economic policies – whether they are implemented or not, whether the present government falls or not – are likely to be France’s authoritarians, led by Marine Le Pen and the far-right National Rally Party.

This is a sorry economic state of affairs repeated everywhere authoritarianism is on the rise.

Peep into the austere corridors of any central bank, economics department or finance treasury anywhere in the world, and you will find the real powers behind any throne: technocrats that favour private markets over public markets; that prefer private spending to public spending and austerity over full employment and prosperity.

They proliferate throughout Africa, Latin America and Asia, courtesy of the IMF and World Bank. But they can also be found in all OECD central banks and finance ministries.

Democracy as overrated

Many technocrats are trained by orthodox economists at the Chicago School of Economics, or influenced by the Chicago School.

Like the most prominent monetarist of all – Milton Friedman – most regard democracy as overrated and a potential threat to the efficient functioning of the market order. In fact they owe their power over the global economy to Hayekian and Friedmanite ideology: namely that democracy distorts the capitalist economy; that markets are better at decision-making than democracy; that international trade should be ‘free; that public spending crowds out private spending, and must be slashed to restore stability to the market economy. That monetary institutions should stand aloof from fiscal institutions; that fiscal contraction must be amplified by monetary tightening. Finally that inflation is a dragon that must be slain with deflationary policies, and the way to do that is to ratchet up interest rates – and tighten credit conditions – regardless of the state of the economy and levels of private and public debt.

Back in 2007, in its edition for 4-10 August, the Economist’s editorial team shared that perspective.

They were optimistic and upbeat:

Economic fundamentals are all sound; it’s a good time for tighter credit conditions…

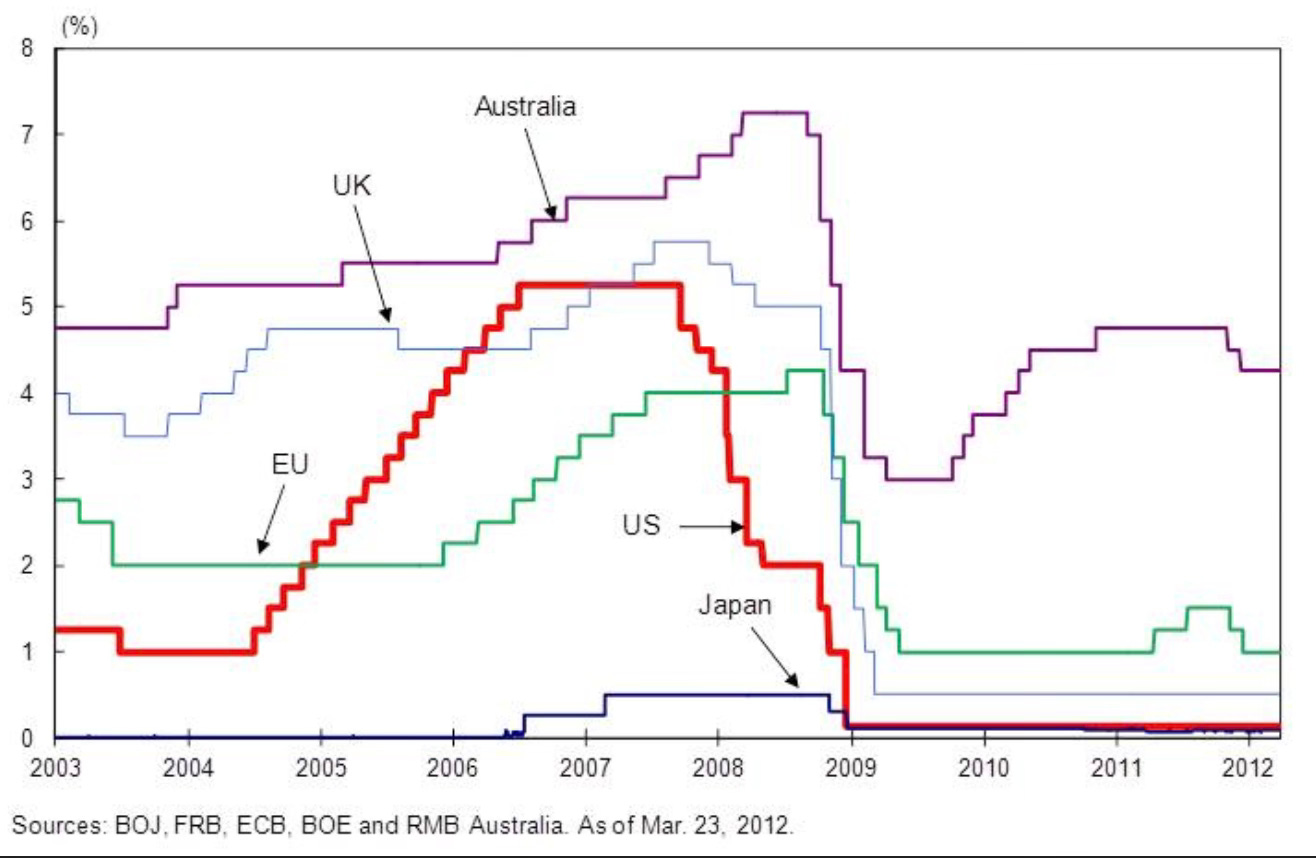

They were not alone. Alan Greenspan and the governors of the Federal Reserve were also tightening credit conditions. Richard Koo, Chief Economist, Nomura Research Institute presented the chart below to an INET conference in April 2012. The red line shows the systematic way in which ‘Maestro’ Alan Greenspan and the Federal Reserve’s Open Market Committee systematically raised interest rates against a vast bubble of US private, sub-prime debt – itself the consequence of ‘loose monetary policy’.

Those hikes were poised – like a dagger – at a debt mountain that was soon to implode and cause catastrophic global economic failure.

On 9th August, 2007 as the Economist magazine with its jolly cover of a technocrat in a corset hit newsagent shelves – inter-bank lending froze and gradually destruction was wrought across the global economy.

Economic fundamentals, it turned out, were not sound.

The power of the technocracy

Economic policies espoused by technocrats at the Economist, Harvard, the LSE and other universities as well as at central banks, had once again blown up the global economy. [In the next post I will share a list of financial crises dating back to 1866 triggered by central bank technocrats that chose to ratchet up interest rates at inappropriate times.]

Tighter monetary policies helped trigger the 2007-9 Global Financial Crisis. In Europe the European Central Bank made a ‘Big Mistake’ as the Global Financial Crisis broke, as James Surowiecki noted in the New Yorker

In July, 2008, on the eve of the biggest financial crisis in memory, the European Central Bank did something both predictable and stupid: it raised interest rates. The move was predictable because the E.C.B.’s president, Jean-Claude Trichet, was an inflation hawk; he worried about rising oil and food prices and saw a rate hike as a way of tamping them down. But the move was also remarkably ill timed. The crisis was already under way, European economic growth had slowed to a crawl, and within a couple of months the global economy had collapsed, inflation had disappeared, and the E.C.B. was forced to slash interest rates, in an attempt to avert economic disaster. That July rate hike was like kicking the economy when it was down.

To prevent further catastrophic failure, central bankers were forced to deploy public monetary and fiscal resources to bail out the entire private, shadow banking and globalised financial system.

Millions of the world’s people lost their homes, their jobs and their small businesses. Many thousands suffered marital breakdowns, depression, anguish and suicide. Wall Street, by contrast, was showered with financial rewards for failure. There was only a feeble attempt at re-regulating the system. Instead the globalised financial system was consolidated – with business-better-than-usual on Wall St.

Whereas before the crisis Wall St banks could be bankrupted – today they are too-big-to-fail and their bosses too-big-to-jail. In May, 2020 Jerome Powell in a CBS interview was asked by Scott Pelley: Has the Fed done all it can do?

Powell replied:

Well, there’s a lot more we can do. We’ve done what we can as we go. But I will say that we’re not out of ammunition by a long shot. No, there’s really no limit to what we can do with these lending programs that we have.

Wall Street took note.

The Global Financial Crisis and the role of Alan Greenspan’s Federal Reserve, both in fueling the crisis through deregulation and the expansion of shadow banking, and then precipitating the crisis with high rates on unsustainable levels of private debt, revealed that central bankers are not detached, objective technocrats, but powerful political actors, whose decisions favour the powerful, and hurt the weak.

Central Bank Independence

The effect of President Trump’s racist and crude attacks on both the governor of the Federal Reserve, and the only black member of the Board, Ms Lisa Cook, has been to galvanise defenders of central bank technocracy, who have rushed to to lionise the governor.

The Economist promptly obliged with an article on of “the insidious threats to central bank independence” by “meddling politicians”. Andy Haldane – ex-chief economist of the Bank of England, took aim at ‘fiscal populism’ – by which is meant I assume, public political pressure. Haldane raised the scary bogey of ‘fiscal dominance’ which, he argued in the FT

poses an existential threat to central banks’ independence and inflation control. When monetary policy is set to meet fiscal ends, central banks become piggy banks.

Piggy banks for governments in place of piggy banks for the City of London and Wall Street?

Fiscal dominance’ Haldane wrote “is one in which governments’ budgetary needs begin to dictate monetary policy outcomes, either through direct financing of fiscal deficits or artificially low interest rates.” (My emphasis)

Interest rates are not “natural” and cannot therefore be “artificial”. Setting the central bank rate of interest is a political act in that the decision has distributive impacts. Creditors gain from high rates. Debtors – and there are millions of debtors – lose from high rates.

Haldane then declares that “we are in an era of fiscal laxity” – a polite way of attacking democratically elected finance ministers as profligate spendthrifts.

The automatic rise in public debt since both the GFC, and the COVID19 pandemic is a consequence of economic weakness and private sector failure. It is not caused by fiscal profligacy.

High levels of public debt, as Haldane well knows, are a response to private financial weakness and failure, leading to falls in private and public investment, falls in tax revenues, and a rise in public spending to compensate for losses brought on by the ‘polycrises’ of this era. Britain’s risk-averse private sector shows no real sign of investing and expanding economic activity. Nor is the private sector willing to rise to the huge challenges facing governments, including demographic change, climate breakdown and high levels of public and private debt.

If and when the private sector recovers (and it may take more public investment to spur on that recovery) incomes, tax revenues and economic activity will rise and public debt will fall. As night follows day.

Central bank ‘independence’

Trump’s vile attacks will invariably scare financial markets, weaken the US dollar and trigger dangerous volatility. He will then be forced to ‘chicken out’ and withdraw, allowing technocrats at the Fed to tighten control over the public monetary system.

Technocrats govern economies in almost every country of the world. Of the many ways in which this control is consolidated one is through the ideology of ‘central bank independence’ and another, the mantra: “there is no money” for the public sector.

The central bank is a public institution (in Britain it is a nationalised institution) whose staff are on the government’s payroll, and whose leaders are appointed by the government.

It is an institution that gains its power and authority from the economic activities of its citizens and from millions of taxpayers that by law are obliged to pour their taxes into the government’s treasury, stretching way into the future, and providing the Bank of England with extraordinary levels of ‘collateral’ .

That is why central banks cannot be divided from other public institutions, no matter how powerful the ideology of ‘independence’. For while the management of monetary policy is a challenging and difficult skill, requiring specialist economic and statistical expertise, nevertheless monetary and fiscal institutions must work in tandem to support the economy as a whole. When fiscal policy is contractionary, expansionary monetary policy can help make up the difference.

Today the Bank of England operates to undermine the UK treasury, as Professor Daniela Gabor explains:

The Bank is supposed to stay out of fiscal affairs. Yet its invisible hand is now depleting the Treasury coffers to boost commercial bank profits. This is the consequence of the institutional arrangement for quantitative easing, through the Asset Purchase Facility (APF) run by the Bank of England. Unique in the world, the APF has cost the UK Treasury around £38bn in 2023 and a projected £40bn in 2024. The Bank of England has projected that under the “optimistic” scenario, the Treasury will pay the APF around 110bn throughout a 2025-2030 government, and net costs could reach £230bn by 2033, beyond Labour’s wildest green spending dreams.

Technocrats and authoritarianism

The actions of central bank technocrats have always had consequences. The rise of authoritarianism is linked to the contraction of economies and the doubling down by officials of austerity policies. The GFC, the Eurozone debt crisis; the humiliation and disciplining of the PIIGs (Portugal,Spain and Greece) by technocrats at the ECB; the COVID19 pandemic, followed by another run on the shadow banking system and a massive central bank bailout of Wall St., and the City of London. Finally, the application of “tighter credit conditions” as the cost-of-living-crisis bit deep into the world’s economies.

Throughout these crises technocratic central bankers have stood aloof: deaf to growing public anger and despair. Blind to the rise of authoritarianism.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate