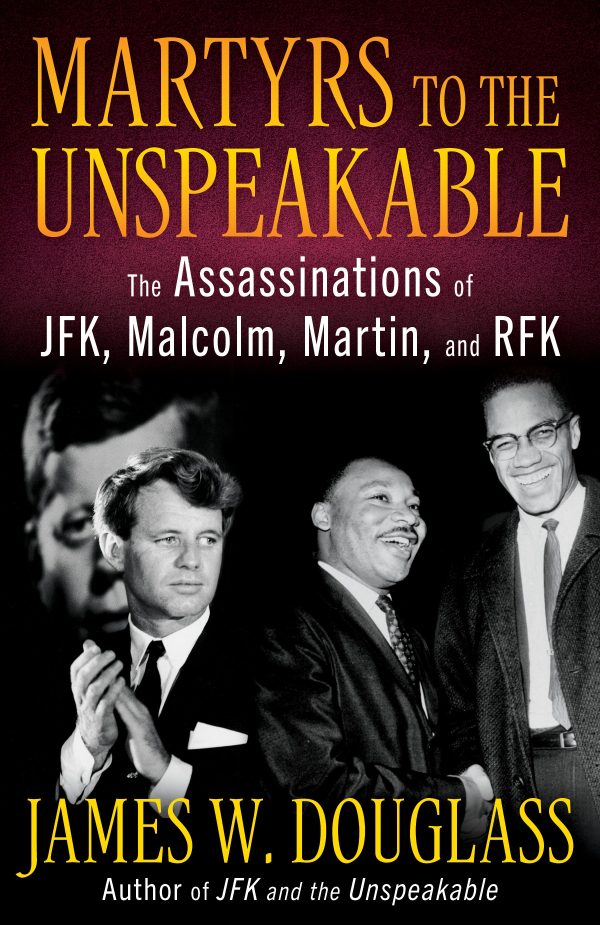

James Douglass, longtime antinuclear activist and author of the bestselling JFK and the Unspeakable, has written his life’s work. Martyrs to the Unspeakable builds on the work of its predecessor, which detailed Kennedy’s turn toward peace during the Cold War and his resulting death at the hands of his own government. Martyrs broadens and deepens the story. It follows four American seekers for peace and justice during the 1960s, John F Kennedy, Malcolm X, Martin Luther King, Jr, and Robert F Kennedy, showing how and why they were killed. The book is a wealth of detail, each page lined with footnotes that are not to be missed. Douglass colors in the remaining spaces in these complex tales with research conducted over decades, interviewing long-forgotten witnesses, drawing from neglected interviews and rewatching old footage.

Despite the dizzying number of references, the reader finds as she settles in not an enumeration of facts but a tangle of rich and human stories taken from the lives of not only the four big players – Malcolm, Martin, JFK, and RFK – but of innumerable characters and witnesses involved in the efforts for peace and resulting assassinations, from famed CIA agent James Jesus Angleton down to the nearly unknown bystanders. It is these last that are most moving. Douglass’ interview with Glenda Grabow, a humble woman from a difficult background who grew up around several of the thugs and gunrunners used by the CIA in the murders of Martin and JFK, shows a dignity and bravery comparable to any of the four men. Grabow, who nearly perished in a car accident after the lug nuts on one tire were loosened, risked her life to give testimony at the King Assassination Conspiracy Trial attended by the author in 1999.

As evidence of US intelligence agencies’ hands in the murders builds, it is these individual stories that made the greatest impression for this reader. Douglass is quietly making his point that history is made from the actions and decisions of individual men and women, great and small – and that their stories inevitably intertwine.

The book is not arranged chronologically, or even by subject. The stories of the murders are woven around the politics of the time – the Bay of Pigs, the Harlem riots, Kennedy’s dialogue with Khrushchev, Israel’s construction of a nuclear weapon at Dimona – dipping us in and out of decades, countries, continents, and characters. Malcolm meets with Martin, Martin initiates the Poor People’s Campaign thanks to a remark by RFK, RFK makes JFK’s dialogue with Khrushchev possible by meeting with the intermediary Georgi Bolshakov. And beyond – Malcolm is sought after by the Hibakusha (survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki), JFK is moved to action by the death, and probable assassination, of Dag Hammarskjöld, Secretary-General at the United Nations and fellow advocate for African independence.

Assembling the book in this way, Douglass’ point makes itself: the tale is one of conversion and dialogue, of growth and change. These four men did not start out knowing what they should do. It was only after making a pilgrimage to Mecca that Malcolm turned from disparaging ‘white devils’ to preaching universal brotherhood. Martin did not speak out against the Vietnam War until he saw pictures of the bodies of burning children. All four have their conversions. It was only after their conversions, and their inability to remain silent about what they had seen, that they were identified as threats.

Douglass shows that it is these four men’s relentless pursuit of the truth that makes such conversions possible. This pursuit is shown by their willingness to listen and to notice. We see RFK walking through tunnels under the ocean to talk to South American miners, Malcolm letting an unknown young man correct him on the meaning of a verse of the Quran, JFK listening to the enemy Khrushchev. It is a willingness to notice those who usually go unnoticed and to talk with people assumed to be enemies – the people we are not supposed to talk to or learn from, whom we are told not to talk to, until in a rise of mutual mistrust we create a knot that is too tight to be untied, as Khrushchev says to JFK at the height of the missile crisis, and can only be cut. In the context of nuclear weapons, the cutting of such a knot can mean the extinction of life on this planet.

There is another thread running through this book: the inevitably opposing thread, the counterforce to the lives of these four men. Through every story and every chapter wind the efforts of US covert intelligence agencies to stamp down on this pursuit of the truth through dialogue. Their tactics are many. As Coretta Scott King said to her son during the King Assassination Conspiracy Trial (which only took place thanks to her filing of a wrongful death lawsuit), “You have to understand that when you take a stand against the establishment, first you will be attacked. There is an attempt to discredit. Second, to try and character assassinate. And third, ultimately physical termination of assassination, in that order.”

All four subjects are relentlessly wiretapped. Witnesses and experts such as the coroner Thomas Noguchi, who found in his autopsy of RFK that the gun must have been fired at no more than three inches from behind the senator’s right ear, contrary to Sirhan Sirhan’s location three feet in front of him, are badgered to change their testimony. We see Sirhan subjected to mind control, Jack Ruby being driven crazy struggling to escape what Douglass calls the “wilderness of mirrors” constructed around him. When none of this works, as Coretta Scott King says, murder is used. Douglass shows throughout the book that all four of his subjects were well aware of their probable violent death.

What efforts to constrain the truth! The Unspeakable in the title has a twist. We are shown what we are not supposed to say – that US agencies can remove their own citizens, even presidents, and that we can in fact negotiate with those labeled enemies. But it is nothing less than speech that bursts through the cracks, takes root, and blossoms. The truth bubbles up from so many of the characters in this book, from the rank and file policeman Baird, who reveals his invitation to join an early attempt to assassinate Martin, to RFK always getting in trouble for saying “the things that were just basically right and decent,” according to his speechwriter, Adam Walinsky. What is Unspeakable is only Unspeakable because it has been presented to us as such, by those who have an interest in doing so. What is Unspeakable is not only the chilling tales of assassinations, coercion, and silent manipulation, but our belief in a better world – ‘the moral arc of the universe’ that ‘bends toward justice,’ in Martin’s words – a world where the poor demand their due, where countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America can be free from depredation. These are the things these men fought for.

The CIA, and at times the FBI, comes down with deadly force in this book. It is indeed frightening. But Douglass shows this is only because they know the power of the opposing force. All four men were populists in the triple sense that they worked for the people, listened to the people, and were loved by the people. RFK never had qualms about going to the center of the action: when he walked into a riot zone in a Washington DC neighborhood in 1968, in one of the book’s many moving anecdotes, “A Black woman came up to Kennedy and did a double take. “Is that you?” she said. He nodded. Taking his hand, she said, “I knew you’d be the first to come here, darling.” Malcolm is shown dispersing a crowd of 2,600 people gathered around a police station in Harlem after the brutal beating of a Black Muslim, “with a simple wave of his hand.” The Kennedys’ picture hangs on the walls of the poor across the US, and even in Latin American slums. As Douglass says, “A peace president needs a people’s movement.” The power of these four men was the power of the people.

Douglass’ last chapter is a masterful account of the dialogue between JFK and Khrushchev during the missile crisis. It is an extended, faithful retelling of a breathtakingly difficult series of negotiations. It is a test case for Douglass’ theme. Douglass shows us, warts and all, what dialogue, in this case dialogue with one labeled the enemy, can mean. It would be easy to condemn JFK as a fool for working with Khrushchev, who deceived him, and Khrushchev as a fool for working with JFK, who he knew was being subverted by his own intelligence agencies. Neither man could afford to be less than as wise as a serpent, but Douglass shows us why such a dialogue was necessary. The generals behind JFK are thirsty for war, with Curtis LeMay, who made no bones about wanting to take out the enemy despite any contingencies, at the head. A similar parade of bloodthirsty generals stands behind Khrushchev. We are reminded that violence is easier than negotiating. Nothing would have been easier than dropping bombs: but at what cost? As LeMay’s protègè General Thomas Power said when briefed about a strategy that would keep the air force he commanded from striking Soviet cities: “Restraint! Why are you so concerned with saving their lives? The whole idea is to kill the bastards! At the end of the war, if there are two Americans and one Russian, we win!”

Martyrs to the Unspeakable neither begins nor ends in the US, but in Israel. Douglass touches only occasionally on nuclear weapons, but they ground the book. What does violence mean, with nuclear weapons? What is the value of negotiation now that we have nuclear weapons? Chapter One shows us Kennedy’s efforts to keep Israel from building its own nuclear weapon system, a system which both countries even today refuse to acknowledge, using the serpentine phrase, “We can neither confirm nor deny…” For Kennedy this was a necessary step in persuading the rest of the world, including the US, to reduce theirs. With yet another, perhaps the greatest, Unspeakable in our midst – weapons that can eliminate all life on earth in the hands of countries trying to acquire absolute power – any efforts by peacemakers to speak against this mighty wave must be crushed. “I believe a key to this untold history,” Douglass says, “is the fact that our government was the first to develop and use nuclear weapons.”

We may be familiar with Kennedy’s efforts to prevent Israel’s acquiring of a nuclear bomb, but most of us have not heard of Count Folke Bernadotte, the United Nations Mediator in Palestine, who was under way to place Jerusalem under the protection of the United Nations when he was assassinated. His story is told in the Epilogue. The protection would have made it possible for the UN to recommend a border between an Arab and a Jewish state. Bernadotte was killed by Yehoshua Cohen, who, as Douglass tells us, “would become David Ben-Gurion’s security guard and closest friend.” The American diplomat Ralph Bunche, Bernadotte’s assistant, narrowly missed being killed when he was delayed on the way to join Bernadotte.

In pointing to Israel, and to a possible peace that was on the brink of being achieved when Bernadotte was killed, Douglass is not so much pointing to Israel as to, in Martin’s words, the fierce urgency of now. This book is not about the past, it is about the present. This book is about all of us. What, Douglass asks, will we do?

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate

1 Comment

Fine literary citizenship. Engaging and grounding. A bulwark of meaning, an icebreaker….