Racial capitalism is in crisis! Again, you say? Of course there are cyclical crises, but something different is going on. In January, the elite World Economic Forum declared the global economy is facing a major potential “polycrisis” as dangerous risks converge, including natural resource shortages. In April, the venerable capitalist economic strategist Albert Edwards warned “we may be looking at the end of capitalism” as he connected inflation to the unchecked quest for greater and greater profit. Just to put this in context, Edwards works for one of France’s largest banks, the 159-year old Société Générale, with assets worth 1.5 trillion euros.

These comments invite loose comparisons to the period before the U.S. Civil War, when Southern strategists were scrambling to give slavery a moral facelift and limit some of its “excesses” before it was too late, as if that were possible.

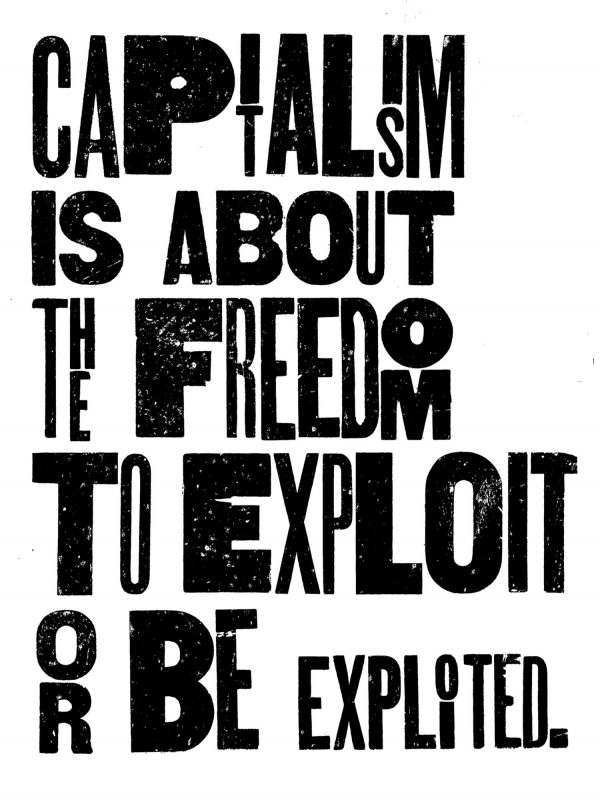

Capitalism is a political and economic system based on the private accumulation of profit derived largely from the exploitation of labor. It is also a racial system because, since it began, it’s used the fabricated notion of “race” and the very real ideology of white supremacy to naturalize hierarchies of power, divide the oppressed, and super-exploit and dispossess large swaths of the world’s population.

Racial capitalism has always been a dynamic shapeshifter, adaptable and malleable to changing times. But at least two points of capitalist vulnerability in the 21st century may prove insurmountable: the existential environmental crisis, and the spiraling growth of a behemoth financial industry that rests on mind-blowing levels of individual, national and world debt.

Banks and hedge funds and big finance have overtaken many manufacturing sectors in profit, snaring 25-30% of all corporate profits while employing only 4% of the workforce.

The climate catastrophe needs little explanation. Forests are ablaze, floods are wreaking havoc, extreme weather is undermining agricultural production, air quality is plummeting, and millions of humans are fleeing unsafe and unlivable homes. Capitalist corporations are the main culprits. The bottom line is that capitalism feeds off of an infinite growth economic strategy — “make more, buy more, waste more” — while the material reality is that we live on a finite planet and are exhausting both its resources and its ability to absorb our excesses. That is a hard crisis to buy your way out of.

Then there is financialization. Thanks to the deregulation of banking, the 1971 change in global monetary policy and the emergence of new financial instruments and formulas for moving money around, a large number of capitalists are making tons of cash not by the traditional means of exploiting workers, but by gambling on the future of certain markets. Banks and hedge funds and big finance have overtaken many manufacturing sectors in profit, snaring 25-30% of all corporate profits while employing only 4% of the workforce. It is like a giant Ponzi scheme or a house of cards, or what British economist Susan Strange labeled “casino capitalism” back in 1986.

The precarity of this system is evident in the 2008 financial collapse that led to so many home foreclosures and bank bailouts, coupled with the more recent smaller bank shutdowns. Who knows what collapse is on the horizon or what the cost of the next bailout will be? The response to the polycrisis, from liberal economists, is to designate this period as some abnormal form of capitalism, some “crony capitalism” or “hyper-capitalism.” But it is just plain old racial capitalism, which has always been a bad deal for poor and working-class people and is now even worse. We see progressive intellectuals (like the economist Thomas Piketty, who titled a recent book Time for Socialism) moving leftward as they confront the reality that capitalism, as we know it, cannot be saved.

As capitalist reformers search for a way to patch up a dilapidated (but still lucrative) economic structure, socialists have the opportunity to organize around a real alternative.

A world to dream. A world to build.

These notes are not to make the deterministic argument that capitalism will soon collapse under the weight of its own contradictions, but to invite us to consider that capitalism is not nearly as fixed and timeless as some suggest. What comes next is uncertain. We see a frightening and formidable authoritarian movement in the United States and worldwide, in many cases propped up by racist narratives. But we also see the growth of cooperatives and solidarity economies, and we see insurgent movements against wealth inequality, capitalist extractivism, heteropatriarchal-infused violence and racist neo-Nazi fanaticism.

As capitalist reformers search for a way to patch up a dilapidated (but still lucrative) economic structure, socialists have the opportunity to organize around a real alternative. In order to be effective, however, we have to ask hard questions and confront tough realities. We have to take mass organizing seriously, and not pretend we have consensus when we don’t. We have to admit past mistakes of movements that, at one time, represented enormous hope. We have to create more democratic structures within our movements, and engage in more rigorous (but respectful) debates about where to go from here; about what type of organizations, strategies and leadership are most important; and about the ideological foundation upon which we build.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate