How many people are out of work? What is the real unemployment rate? We don’t know. What we do know is that the true number is far higher than the unemployment rate at any given time.

There are some measures that purport to give a better answer than the standard unemployment rate, such as the U-6 in the United States and R8 in Canada, which, because they use more expansion definitions, tend to yield numbers around twice as high as the standard definition does. But even those numbers almost certainly underestimate the true extent of unemployment and underemployment.

One attempt at calculating a true figure, published by the Ludwig Institute for Shared Economic Prosperity, says that the true rate for the United States is 24.3 percent. This statistic, what the Institute calls the “True Rate of Unemployment,” measures “the functionally unemployed, defined as the jobless plus those seeking, but unable to find, full-time employment, and those in poverty-wage jobs.” That is calculated by using Bureau of Labor Statistics data and adds to the more expansive definition of unemployment (the U-6) those who earn US$25,000 or less annually before taxes, which the Ludwig Institute defines as below a living wage.

By contrast, the official U.S. unemployment rate for June 2025 is 4.1 percent and the U-6 unemployment rate is 7.7 percent, up three-tenths of a percentage point from a month earlier. The official unemployment rate, used by governments around the world, is the standard International Labour Organization definition: those collecting unemployment benefits and are actively searching for work (often the latter is necessary to qualify for the former). If your unemployment benefits have run out, congratulations — you are no longer unemployed! The U-6 number represents all who are counted as unemployed in the “official” rate, plus discouraged workers, the total of those employed part time but not able to secure full-time work and all persons marginally attached to the labor force (those who wish to work but have given up).

The Ludwig Institute says its goal is to establish a more accurate gauge “by preventing bad jobs and parttime jobs from looking better than they are on paper — something that the [Bureau of Labor Statistics] unemployment rate fails to do.” A better measurement is needed: “Although not technically false, the low rate reported by the BLS is deceiving, considering the proportion of people who are categorized as technically employed, but are employed on poverty-like wages (below $20,000 a year) and/or on a reduced workweek that they do not want. Neither of these factors [are] conducive to prospering, nor to providing for a family.”

Calculating its “True Rate of Unemployment” back to 1995, the Ludwig Institute finds that unemployment has never been lower than 22 percent and reached a peak of 34.8 percent in February 2010, when the world’s economy was still struggling in the wake of the 2008 economic collapse. The closest the official rate and the true rate were was in April 2020, when the Covid-19 pandemic caused an economic shutdown; that month, the official U.S. rate was 14.2 percent and the Ludwig true rate was 34.2 percent.

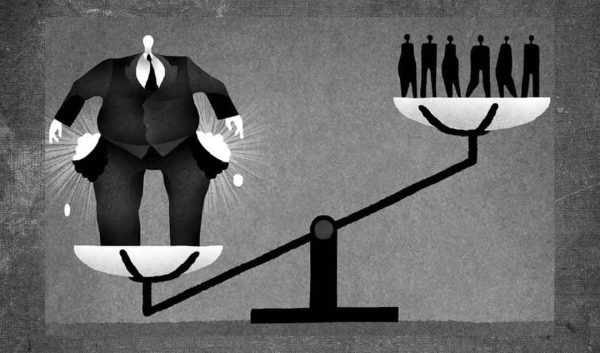

“The harsh reality is that far too many [in the United States] are still struggling to make ends meet, and absent an influx of dependable, good-paying jobs, the economic opportunity gap will widen,” Institute chair Gene Ludwig said. “Amid an already uncertain economic outlook, the rise in functional unemployment is a concerning development. This uncertainty comes at a price, and unfortunately, the low- and middle-income wage earners ultimately end up paying the bill.”

Undercounting the unemployed is the norm

Finding similar statistics for other countries is more difficult, but the past has shown that unemployment is similarly underreported in other countries. Canada’s official unemployment rate for June 2025 is 6.9 percent and its R8 unemployment rate for that month is 8.6 percent, a drop of a half a percentage point from May. The Canadian R8 counts people in part-time work, including those wanting full-time work, as “full-time equivalents,” thus underestimating the number of under-employed. How much does it undercount? A lot it would appear. Unifor, Canada’s largest private-sector union, issues its own monthly report. For May 2025, Unifor reported the Canadian underemployment rate was 15.9 percent. That number “adds to the unemployment rate all involuntary part-time workers and the marginally attached (i.e. those who wanted to work but who were not able to actively search for jobs due to extenuating circumstances).”

Unifor also reports that 21 percent of Canadians earn low wages, defined as hourly wage earners earning less than two-thirds of the median hourly wage. As there must be some low-wage workers who are already counted in the underemployment rate, it would take research to determine a Canadian underemployment number akin to the Ludwig “true rate” for the United States. But it would seem likely that any such Canadian rate would at least approach the U.S. rate.

We could repeat this exercise for other countries. The latest British official unemployment is 4.6 percent while the economic inactivity rate is 21.3 percent; the latter is defined as “people not in employment who have not been seeking work within the last 4 weeks and/or are unable to start work within the next 2 weeks.” For the European Union, the latest reported unemployment rate, for May 2025, is 5.9 percent, while the “labour market slack” was reported at 12 percent for 2023, the latest figure available. Here again, if it were possible to calculate a “true rate” for underemployment, such a rate would be considerably higher.

It is fair to conclude that employment in the capitalist world is more precarious and less available than we are led to believe. One additional measure of how capitalism continues to fail to provide sufficient work is the labor participation rate; a straightforward measure of how many people of working age are actually working. In the United States, this rate has consistently declined since 2001, when two-thirds were employed. That rate is now down to 62 percent. Finally, we can examine how much of gross domestic product goes to wages. That number is also declining. Having peaked at 62 percent in 1969, in 2024 only 42 percent of GDP went toward wages. Yes, you are earning less.

Even with declining wages, bloated corporate profits, greater inequality and ever more money shoveled into the gaping pockets of financiers through dividends and stock buybacks, what do representatives of capital tell us? Commentaries by orthodox economists, conservative think tanks and business publications such as Forbes say the problem is that wages are too high. The U.S. Federal Reserve, the world’s most important central bank, agrees that wages are too high. Yet there were untold trillions of dollars to give to financial titans. For example, the US$10 trillion handout to the financial industry through programs artificially propping up financial markets in just the first two years of the Covid-19 pandemic, on top of the further trillions handed out to business in those years while employees received crumbs and layoff notices. And all that followed the $16.3 trillion committed to the financial industry by the world’s four largest economies in the wake of the 2008 collapse despite the fact that the same industry was responsible for the collapse.

If you have regular work, you are among the fortunate

All these statistics reflect the state of working people in advanced capitalist countries. If we were to zoom out and examine trends in work for the world as a whole, conditions are considerably worse. The International Labour Organization, in its World Employment and Social Outlook for May 2025, reports that 2 billion people — representing 58 percent of all employed workers worldwide — have only informal work. People with informal work outnumber those with formal work, and the rise in informal work is faster than that of formal jobs. This trend is particularly strong in Africa, where the International Labour Organization (ILO) estimates that 85 percent of workers are informal. The ILO also reports that, globally, the share of labor income has been declining, and if the labor share had stayed constant since 2014, the world’s workers would have made a composite US$1 trillion more in 2024.

I’ve thrown all these numbers around to conclude what you have likely already concluded: We are getting more screwed. So we are. People of Color are even more under the gun than White people, and women are more under the gun than men. You are not alone if you are out of work.

Can this be reformed? The answer clearly must be no. Unfortunately, the usual weak-tea prescriptions are on offer from the International Labour Organization in its report. The ILO, in its conclusion, advocates “active labour market policies, social protection measures and robust public employment services” and suggests “dialogue between governments, employers, and workers.” Those would be nice if they could be achieved, but given that capitalism presses down ever harder, and has done so throughout its history in the absence of a strong, sustained, militant movement — and when the movement quiets, the reforms are taken back — if such activities were to work they would have already been done. History is quite clear here, and has been for a very long time. For centuries.

Speaking nicely to corporate executives and financiers and the political office holders who carry out the preferred policies of those executives and financiers, and expecting them to have an epiphany is, to put it mildly, quite unlikely. And those few executives who might be personally inclined to ease up and hand out some nice raises as a reward for hard work and high profits are constrained from doing so due to the unrelenting pressure of capitalist competition. Nobody controls the capitalist system; it has its own momentum to which all companies must bow to remain competitive and, ultimately, in business. The unceasing competition of capitalism, its relentless drive to enclose ever more human activity within its logic of profit at any cost, mandates the world we now live in.

Stagnation, declining wages and the ability of capitalists to shift production around the globe in a search for the lowest wages and lowest safety standards — completely ignored in the orthodox hunt for economic scapegoats — are the norm. Our need to sell our labor, the resulting reduction of human beings’ labor power to a commodity, and the endless competitive pressures on capitalists to boost profits underlie the world economic system. A race to the bottom is what global capitalism has to offer, and all it can offer.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate