Howard Zinn’s book on SNCC was written in 1964. Yet, here I am writing a review in 2025, a good 60 years later. It feels appropriate to do so. There is of course the usual wisdom about paying attention to history for its relevance today, especially the history of social movements. There is also the fact that the MAGA movement has as its primary goal undoing the victories of the civil rights movement. But most of all, there is the inspiration to be drawn. The segregation era was one of the darkest eras of American history, and if it could be defeated, then so can MAGA.

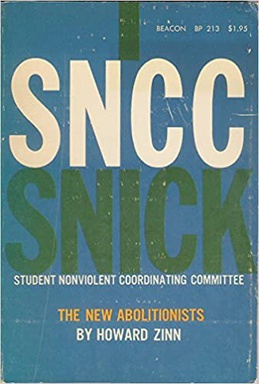

Zinn opens his book with these powerful words. “For the first time in our history a major social movement, shaking the nation to its bones, is being led by youngsters.” The pathway lit up by the Brown v Board of Education decision in 1954 and the Montgomery Bus Boycott “flared into a national excitement with the sit-ins by college students that started the decade of the 1960s. And since then, those same youngsters, hardened by countless jailings and beatings, now out of school and living in ramshackle headquarters all over the Deep South, have been striking the sparks, again and again, for that fire of change spreading through the South and searing the whole country. These young rebels call themselves the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee.” Zinn refers to these young rebels as the new abolitionists, referring to the original abolitionists fighting slavery. Although the civil rights movement was not as non-violent as is usually believed, it was surely more non-violent than the anti-slavery movement. Also unlike the original abolitionists, the new abolitionists were disproportionately young.

Tales of inspiration abound. For instance, consider the story of Bob Moses – a Harvard graduate, who could have chosen to pursue a successful career in mathematics, instead choosing jailings and beatings while registering people to vote in Mississippi. While it is easy to pay attention to the jailings and beatings, this writer was moved to tears by simple acts of courage as described by Zinn thus: “ As about a hundred Negro men, women, and youngsters, singing and praying, approached the Leflore County Courthouse, the police appeared, wearing yellow helmets, carrying riot sticks, leading police dogs. One of the dogs bit twenty-year-old Matthew Hugh, a demonstrator. Another, snarling and grunting, attacked Bob Moses, tearing a long gash in his trousers. Marian Wright, a young Negro woman studying law at Yale, was on the scene that day:

I had been with Bob Moses one evening and dogs kept following us down the street. Bob was saying how he wasn’t used to dogs, that he wasn’t brought up around dogs, and he was really afraid of them. Then came the march, and the dogs growling and the police pushing us back. And there was Bob, refusing to move back, walking, walking towards the dogs.”

There was active participation from white people too, e.g., people like Bob Zellner, Julian Bond, Diane Nash, James Zwerg, who made tremendous sacrifices for the cause of civil rights. When someone wrote to activist Ralph Allen that:

“White boy, only a fool

Would leave his heaven

On earth just to fight

For undeserving Negroes”

Ralph Allen replied thus: “I do not understand Gloria. It’s no heaven on earth I left. Depends on what you mean by heaven. If you mean a place where everyone has so much money they have no sensitivity – no love, no sympathy, and no hopes beyond their own narrow little worlds… But to me the conceited, loud, self-centered All-American free white and twenty-one college boy stinks. I know, I was one. But something happened to make me human….”

Besides stories of inspiration, the book is replete with lessons in movement building, which carry the extra credibility of being a first-hand account by a movement member. First is what it even means to be radical. Now, a large part of the movement was about voting rights, and the primary tactic used to fight for voting rights was to register Black voters (who at the time were registered in astonishingly low numbers.) Registering Black voters by itself is no radical act. But registering Black sharecroppers in Mississippi absolutely was. It required tremendous courage – a willingness to endure jailings and beatings, thought and persistence. It is a lesson to activists of today that radicalism doesn’t come from slogan chanting or posturing online; on the other hand, what seem like reforms in context are radical.

We also get insights into movement decision making. The initial focus of SNCC was on sit-ins and freedom rides, and it was decided later to also focus on voting rights. When the movement decided to spread its wings to Mississippi, the people on the ground (like Bob Moses) felt that sit-ins and freedom rides, while critical, wouldn’t succeed the same way in Mississippi as they did in other places. The reason was that it did not resonate as much with the older Black people in Mississippi, who instead preferred fighting for voting rights, and it was important to have a focus that increased the chances of mass mobilization. Although the decision looks obvious in hindsight, at the time, it generated a debate within SNCC, where significant parts of the leadership wanted to focus exclusively on sit-ins and freedom rides. As a corollary to this point, it is worth noting that although SNCC is seen as a young people’s movement, as a part of the mobilization among sharecroppers, SNCC mobilized older Black people. This is best illustrated by the rise of Fanie Lou Hamer who became a national leader when she was in her 40s. Zinn describes Hamer thus: “..she walks with a limp because she had polio as a child, and when she sings she is crying out to the heavens.” Hamer described her commitment to the movement in this way: “The thirty-first of August in ‘62, the day I went into the courthouse to register, well, after I’d gotten back home, this man that I had worked for as a timekeeper and sharecropper for eighteen years, he said that I would just have to leave….So I told him I wasn’t trying to register for him, I was trying to register for myself….I didn’t have no other choice because for one time I wanted things to be different.”

There is also the relationship of the movement overall with the Democratic party. Now, it was well-understood within the movement that the Democratic party were no allies. Yet, it was important that the federal government was Democratic. This is because the movement overall used legal action in conjunction with direct action. Partly, this was a direct mode of effecting change, but also in order to set guardrails around what state governments in the deep South could do. While the state governments in the deep South were able to inflict damage on the movement through jailings, beatings and outright murder, they were unable to shut the movement down. This was because the movement used the federal apparatus to, for instance, reduce the duration of jail sentences from months to weeks. These tactics had a greater chance of success because the federal government was Democratic. In 2025, we live in dark times with a fascist as President threatening to undo the tremendous victories of the civil rights era. It is crucial in these times to recollect, more than the specific lessons of the civil rights movement, its spirit of resistance. As Zinn puts it, we owe the civil rights movement a debt for “releasing the idealism locked so long inside a nation that has not recently tasted the drama of a social upheaval.” It is time now to release the same idealism against the stench of fascism. We shall overcome.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate