It was a hot day in June 2018. We marched past fruit trees and reached the meeting point, where he sat under a large walnut tree with three other guerrillas. We later learned that he had chosen this spot because the shade of the tree provided both coolness and safety. His choice was not without reason; he was a target of the Turkish state, which has declared all Kurdish freedom fighters to be outlaws.

We were in the Qandil Mountains—part of the Zagros Mountain range—on the arbitrarily-drawn border between Iraq and Iran. About 100km further north they border Turkey; and to the west lies the border with Syria. Challenging these arbitrary borders, however, is Kurdistan.

Rıza Altun wore gray-green clothing—the uniform of the Kurdish guerrillas—which covered his slender body. He greeted us with a smile on his small, narrow face. His hair had grayed since we had met in Paris, about ten years ago. However, his politeness and warmth towards his guests remained unchanged. Contrary to his stern image, he welcomed us with modest, loving warmth. Smiling, he said to me: “You’re not getting any older either.”

Hospitality in the Mountains

When expressing love and sincere affection, he was often humorous. First, he offered us cool water. “Look, this is organic water, which you rarely find in Europe and pay a lot for,” he said with a smile, adding that they don’t get it from bottles, but directly from the spring. “You’re lucky, there are no drones flying over the Qandil area today. That’s why we can make a fire and offer you our tea.” The “guerrilla tea” was made from black tea, boiled in a kettle over a wood fire. Since the smoke from the fire indicated that guerrillas might be there, these fire pits quickly became targets. While we drank tea, he asked questions to get to know the group. He emphasized how important the group was, having come from Europe to the mountains of Kurdistan to research and report on the revolution here; generally, interest in the topic is restricted due to the international criminalization of the Kurdish freedom movement.

We—a group from the German TATORT Kurdistan campaign—had been thrilled to have the chance to meet with an important pioneer of the Kurdish revolution. We had wanted to meet with a member of the Executive Council of the Community of Societies of Kurdistan (Koma Civakên Kurdistanê, KCK), the umbrella organization of the revolution in Kurdistan and, when we learned that Rıza Altun would be participating, we were overjoyed. Since 2012, he had played a key role in the establishment of the KCK’s Foreign Relations Committee. In addition to diplomatic activities, his responsibilities included explaining and representing the ideological and political position of the Kurdistan freedom movement to the outside world. In his interviews, he offered detailed analyses of political developments in Kurdistan and the Middle East, as well as philosophical perspectives for resistance fighters and socialists worldwide. With great admiration and interest, we listened to Heval Rıza for over five hours and were very reluctant to leave.

During a break, a delicious meal was prepared for us in the midst of the mountains. Only after we had eaten our fill did he tell the group that he had helped prepare the meal himself. This came as a surprise to the group, but for me it was a confirmation: I was familiar with his selfless nature from our past time together, from Paris between 2002–2007 to various other meetings that followed.

Kurdistan: Revolution amid great difficulties

Our intense discussions were published (in German) as a brochure entitled “Our strategic allies are the anti-systemic forces of this world.” It describes in detail the structural crisis of capitalism, the political situation worldwide, and the challenges of internationalism from the perspective of the Kurdistan freedom movement. “No revolution is as difficult as ours in Kurdistan. Yet no one has stated that our efforts towards a revolution are particularly great or outstanding. For we are struggling with the greatest difficulties in the world and trying to pave the way for revolution through the most interesting approaches,” he said, referring to developments in Eastern Kurdistan. There, in the predominantly Kurdish areas of northern and eastern Syria, a self-governing administration (the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria or DAANES, known colloquially as “Rojava”) was organized in the wake of the Arab Spring and the subsequent uprising against the Assad regime in Syria in 2011.

The Rojava Revolution is a crowning achievement of the liberatory struggle. The political model of society established there is based on the combined strength of the Kurds, Arabs, Assyrians, Armenians, Yazidis, and the many other ethnic groups in the region, even amidst the ongoing conflict in Syria. The concept of democratic confederalism, which promotes the self-organization of society at all levels and the freedom of women, is at its heart.

Previously, it was very difficult for the Kurdish freedom movement to reach international comrades with its message. While the Turkish government fought the uprising (using every illegitimate means at its disposal), it demanded the international criminalisation of the PKK in return for geostrategic, economic and political concessions as a ‘legitimate’ state partner. As a result, in mainstream politics and the mainstream media, victims became perpetrators and perpetrators became victims. But the resistance fighters are not dismayed by these measures. With shining eyes, Altun expressed his conviction: “The struggle is marked by difficulties, but the most exciting thing about all these difficulties is the search for freedom itself. This search is breathtaking.”

For the anti-systemic forces and especially for the socialists of this world, Rıza Altun was and is a bearer of hope and a source of inspiration who, through his life, set an extraordinary example of how to steadfastly resist oppression and fight for liberation. The history of the Kurdistan freedom struggle, led by Abdullah Öcalan, is also his history.

History within history

The Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), founded in 1978, forms the core of the entire Kurdistan freedom movement. On May 12, 2025, the PPK announced that its co-founders Rıza Altun and Ali Haydar Kaytan had fallen, alongside news of its own dissolution and the end of the armed struggle, as part of a renewed peace process with the Turkish state. At this moment, the movement redefined the form and institutionalization of its struggle. Through half a century of struggle, the PKK has asserted the existence of the Kurdish people and been at the forefront of fighting for social and political change to secure their rights and dignity. The leadership role of Abdullah Öcalan—abducted on February 15, 1999, as a result of an international conspiracy and imprisoned on the island of İmrali ever since—has been decisive in this process.

In a manifesto addressed to the 12th Congress of the PKK, Öcalan said the following: “The PKK is a movement that makes the reality of Kurdistan visible and its existence indestructible. The next step is to achieve freedom. The free society will take shape on the basis of communality and along moral-political lines. The realization of this step does not seem possible with the PKK.“ Though it still requires legal and official recognition, Öcalan acknowledged that ”the existence of the Kurds has been recognized, thus the main goal has been achieved.”

Öcalan’s goals are the movement’s: an existence beyond denial, oppression, and assimilation; a free, democratic, ecological future for Kurdish society; all based on women’s freedom throughout the states in which they live. This was confirmed at the 12th (and final) congress of the PKK.

Inspiring pioneers: Altun and Kaytan

Öcalan also shared a message of condolence for his two fallen companions: “Their place in our struggle for national existence and democratic communality is permanent. Even in the new paradigm and its institutionalization, they will forever fulfill their role as pioneers with fundamental inspiring values. As permanent guides, they will live on and be kept alive in our struggle.”

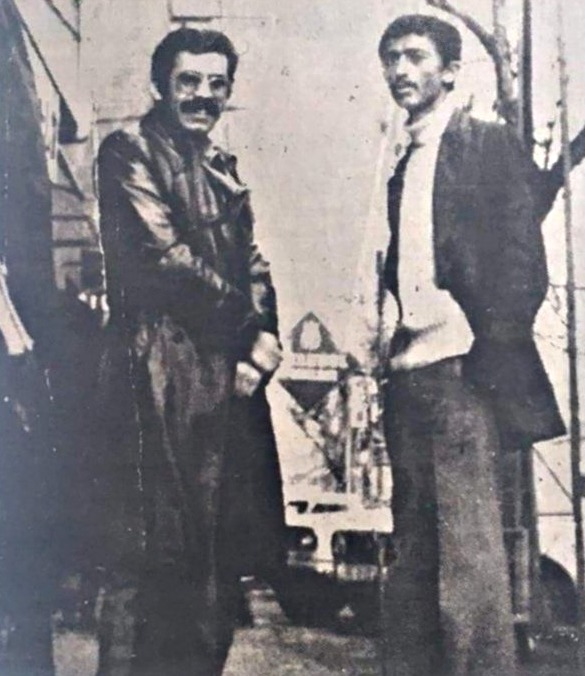

Öcalan and Ali Haydar Kaytan—killed on July 3, 2018—met in Ankara in 1972 while studying. His role in the Kurdish freedom movement, which we will discuss in more detail in another article, is just as important, diverse, and instructive as that of Altun. In the years that followed, they attracted other companions from the student body, including Haki Karer, Kemal Pir, and Duran Kalkan (all of Turkish origin) as well as the Kurds Mazlum Doğan, Mehmet Hayri Durmuş, Cemil Bayık, Mustafa Karasu, and Rıza Altun. They lived in Tuzluçayır. Tuzluçayır, a poor neighborhood in Ankara known at the time as “Little Moscow” because many leftists and Kurdish–Alevi families like the Altuns had settled there. It was their third relocation within a country in which they were “homeless.” Due to economic hardship and conflicts with nationalist Turks from neighboring villages, Rıza Altun had to move away from the village of Küçüksöbeçimen in Sarız with his family at the age of six. Like the other villagers, his family—as Alevi Kurds from the Dersim and Sivas regions—were forcibly resettled because they had resisted the Turkish state’s policies of exclusion and discrimination. So even then, he was familiar with a tradition of resistance. He learned at an early age to reject assimilation and oppression.

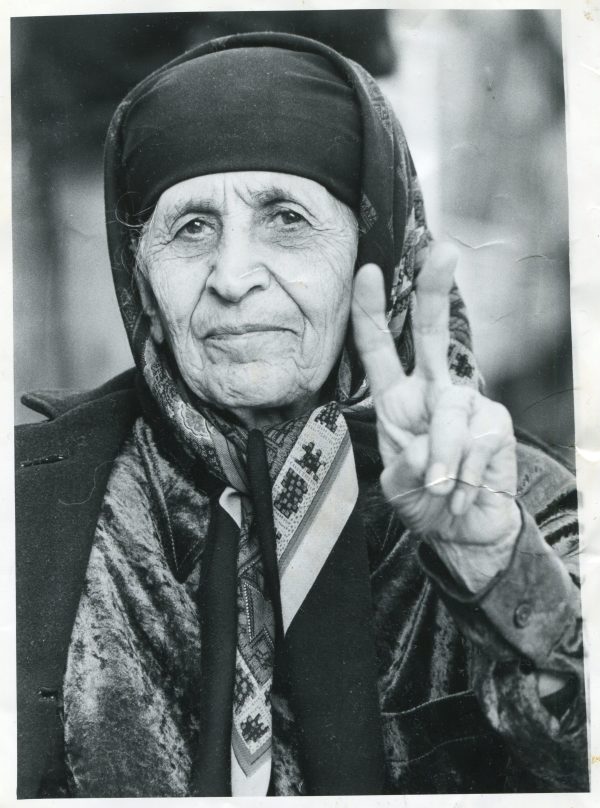

Always defend yourself against evil

When he was still a child, his mother Hatice showed him the path of rebellion, thus preparing him for his later life: “Don’t come to me crying. You must always fight against evil; that is the only way you can stay on your feet.“ This background no doubt helped Rıza Altun to integrate quickly into the group of ”friends” he met in Tuzluçayır. In his neighborhood, Rıza Altun was the leader of an anti-fascist defense group. His leadership qualities had also impressed Kemal Pir. The then–still small group around Öcalan, to which Kemal Pir belonged, was ideologically and politically strong, but Rıza Altun’s group was much larger. Kemal Pir, who was strong in theory and ideology, tried to convince Altun to join the movement. On the other hand, Altun was initially skeptical about Pir. Altun was Turkish and was looking for contacts and new friends in the left-wing neighborhood. To dispel his doubts and test Pir, he invited him to take part in actions against the fascists in the neighboring district. “My skepticism quickly vanished after Kemal had fought harder against the fascists than many in my group. He was like a preacher and at the same time an unyielding activist. That inspired me. Over time, I began to admire him, because wherever he was, there were actions and debates.”

It was also Kemal Pir who introduced Rıza Altun to Öcalan. He was quickly accepted into the group. During this time in Tuzluçayır, Rıza Altun’s house and his family regularly hosted the group.; Hatice often cooked and cared for Rıza’s friends with love and affection.

The core of the freedom movement forms in Ankara

They held many meetings and sought new comrades-in-arms. However, they were not yet thinking of founding a party or waging an armed struggle. Rather, in the mid-1970s, they were a group of about 25 left-wing students and young people in Ankara who were searching for something new: based on socialism, but in Kurdistan. As in other parts of the world at that time, the left was causing a stir in Turkish politics. In the spring of 1972, the ideological pioneers of the Turkish left—including Deniz Gezmiş and two of his companions—were executed by the Turkish state and Mahir Çayan and his friends were killed in a military ambush while protesting the death sentences. This milieu influenced Öcalan, who was arrested during another protest and spent seven months in prison.

Nevertheless, the successors of this revolutionary left were also influenced by the state’s denial of the Kurds, which manifested in various ways. The attitude of the Turkish left was a dilemma for Öcalan, who from the beginning was the natural leader of the Apocular (Apoists) group or Kürdistan Devrimcileri (Kurdistan Revolutionaries). The group’s offensive approach to this dilemma gave it momentum in the following years and helped it quickly gain widespread support in Kurdistan, which Öcalan described as a “colony” due to state policy.

Solidarity, love, and indispensability as character traits

The group had an idea, but they lacked sufficient financial and material resources to implement it. The ideological and philosophical idea of the Kurdistan freedom movement, which is supported by millions of people today, was developed by this core group back in 1973–1978. Only a few members of this group are still alive today.

Remembering these difficult early times, Rıza Altun stressed the vital nature of friendship: “In the group, everyone had to constantly give their all to create something whole. We were able to develop by giving our all and sacrificing ourselves. This created a very special feeling and atmosphere among us. The most important characteristics of our group were solidarity, love, and indispensability among friends. These qualities later shaped the character and spirit of our liberation movement.“

In May 1977, Haki Karer, who had brought the idea of the Apocular to the Kurdish cities, was assassinated in Antep as a result of a conspiracy by a group that has ties to the Turkish state. In Ankara, the group was unarmed and had difficulty obtaining a few pistols for self-defense. As luck would have it, Altun was able to procure them. Karer was the first fallen comrade of the Apocular and remains a key source of inspiration for the movement even today. Öcalan referred to him with great respect as his “hidden soul.”

Altun’s Group in Antep

After Haki Karer’s death, Öcalan came to the conclusion that only the founding of a party could do justice to his memory. He then drafted the program for the PKK, which was founded on November 27 near the city of Diyarbakır. But there was a more pressing task to attend to first: vengeance. Rıza Altun, who was recovering from a serious accident in Diyarbakır, was the perfect man for the job. Öcalan dispatched Altun to Antep, where hostile fascists and rival Turkish leftists had intensified their attacks against the Apocular.

Altun had been active in Antep before, but his second visit had something special about it, which he described as follows: “Due to the fierce attacks, our friends in Antep could not go outside and move freely. The pressure was enormous. After the murder of our friend Haki, there was a gloomy atmosphere created by the state. Our leader Öcalan said, “We can no longer accept this situation. Form a group and fight against it.” He then formed a group of five trusted friends, saying, “It was a completely independent and autonomous group, distinct from the political and organizational groups. We had to wage a real defensive battle, but we needed heavy weapons such as Kalashnikovs. In order to repel the attacks, we had to launch an even more terrifying attack. At that time, our group had only one Kalashnikov, which we used wherever it was needed. We took it to Antep. When we supplemented our existing weapons with it, we became practically invincible. Within three months, everything that needed to be done was done. The situation in Antep returned to normal. In mid-1978, our leader ordered us to cease our activities.””

In the crosshairs of the Turkish state

Even then, the group had no intention of waging an armed struggle. Rather, it was about asserting itself politically. With this in mind, they made preparations to found a political, socialist party that would campaign for the rights of the Kurds.

With the founding of the PKK, the group came under the scrutiny of the Turkish state. At the same time, the military was rampaging across the country, leading to a military coup on September 12 of the following year (1980). Dozens of leading cadres had already been imprisoned in various operations, including Mazlum Doğan, Kemal Pir, Mehmet Hayri Durmuş, Mustafa Karasu, and Rıza Altun in the summer of 1979.

The military coup led to a violent wave of repression against left-wing, opposition, and progressive forces. There were over 600,000 arrests, thousands of victims of torture, and over 170 deaths. Tens of thousands of people fled abroad. The government was deposed, all parties were banned, and a fascist military junta under Kenan Evren was established. The consequences of the coup continue to shape politics in Turkey to this day and have permanently eroded the foundations of democratic order in the country.

Resistance in Prison

In 1980 and the following years, numerous PKK cadres and sympathizers were imprisoned in 5 Nolu Cezaevi (Prison No. 5) in Diyarbakır, which the Times ranks among the “ten most notorious prisons in the world.” It is not without reason that this place is known as “The Hell of Diyarbakır” (Turkish: Diyarbakır cehennemi). Sadistic military personnel attempted to break the political prisoners with brutal methods of torture. Altun said, “They were human-like, but not human. They tortured us in ways that the human mind cannot bear.” But he and his companions did not allow themselves to be broken. Mazlum Doğan—another pioneer of the movement in Ankara—was famed for his resistance in Diyarbakır prison until, on March 21, 1982, he sacrificed his life to make a political statement.

In protest against the inhumane conditions in Diyarbakir prison, the pioneers Kemal Pir, Hayri Durmuş, Akif Yılmaz, and Ali Çiçek began a hunger strike on July 14, 1982. They demanded an “end to torture, enforced military discipline, and uniform clothing.” This action was not only intended to draw attention to the situation in prisons; It was also intended to send a signal to the people outside the prison to rekindle the struggle against the fascist military junta. In the course of this action, Kemal Pir, Mehmet Hayri Durmuş, Ali Çiçek, and Akif Yılmaz lost their lives. This resistance in Diyarbakır Prison No. 5 strengthened popular support and established the culture of the “July 14 Resistance,” which still guides the movement today.

‘Stand Tall!’

The resistance actions of his companions—including Kemal Pir and Mazlum Doğan in prison, as well as the organization outside it—brought Altun new responsibilities. He took over the leadership of the prisoners and participated in many subsequent hunger strikes. He was transferred to at least eight different prisons in Turkey, and his mother often struggled to find him to visit. She was like a guardian angel, always by his side when he faced difficulties. Wherever he was moved, he continued to resist the military dictatorship and thus became a symbolic figure of prison resistance. With courage, wit, and unbroken determination, he fought to preserve the dignity, hope, and mental balance of his fellow prisoners. Altun explained the following example: “They tried to break us with torture and insults. One day they wanted to impose uniform clothing on us. I was one of those responsible. First they took me away and tortured me. Then they gathered all the other prisoners in the courtyard. They threw me to the ground in front of everyone else. The prison director threw the clothes at my feet and said, ‘Rıza, from now on you will wear these clothes, and we will start with you.’ Blood was running from my mouth. I could hardly open my eyes and said to the other prisoners, ‘I will not wear them. And I will deal with those who do wear them.’ His comrades joined his protest—not out of fear, but so as not to feel ashamed before him. Altun’s unbroken will lead to success “In fact, I prevented the switch to standard clothing, but I was tortured for so long that I was unconscious for days.”

Throughout his time in prison, H. Rıza refused to give an inch to the state. He found the courage to continue where others had lost hope. For him, there was always a way to try to achieve his goal, and he taught his fellow prisoners the same. That was his uniqueness and strength. Abdullah Kanat, who spent eight years in the same prison as Rıza Altun, said: “Altun was a friend who took a leading role and made no compromises.” Another cellmate, Mahmut Manas, said: “His resilience and attitude always encouraged us. He always told us: ‘Stand tall!’”

1984: The Start of Armed Struggle

The prison resistance affected the Kurdish freedom movement outside of the prison walls, too. However, Öcalan had left Northern Kurdistan in 1979 for Lebanon (traveling via Kobanê in Northern Syria). The movement, weakened by numerous arrests, attempted to organize itself politically. At that time, the progressive Palestinian movement was a gathering place for many international movements, where ideas and experiences were exchanged. The PKK took advantage of this and, starting in 1982, organized itself militarily in the Syrian-controlled Bekaa Valley in Lebanon, where it set up a training camp. On August 15, 1984, the PKK launched an armed struggle against the Turkish army, which it sustained throughout the 1980s. This guerrilla war broke through the Turkish state’s policy of denial. It made headlines and sparked debates about the Kurdish question and the conflict both at home and abroad. The Kurds who had fled organized themselves, particularly in Europe, and brought the issue to the international stage with large demonstrations. The Kurdish population’s support for the PKK and, conversely, international state support for the Turkish state grew day by day.

NATO fully supported its member state, which also included criminalizing the PKK’s liberation struggle. Due to the PKK’s intensifying military actions, a state of emergency was declared in Turkey’s Kurdish provinces in 1987 under the reign of Kenan Evren. In an attempt to deprive the PKK of social support, more than 4,000 Kurdish villages were destroyed by the Turkish military during these years. Thousands of “unsolved” (Turkish: faili meçhul) murders were committed, thousands of people disappeared, and millions of Kurds were driven to Europe and the cities of Turkey through systematic ethnic cleansing. Documentation of countless massacres, rapes, tortures, and arrests can be found in the documents of human rights organizations.

Rıza Altun is Released

Until 1989, Turgut Özal was formally the prime minister under Kenan Evren’s fascist military junta. On October 31, 1989, he was elected civilian president by parliament. In order to defuse the Kurdish question, he emphasized that his grandmother had been Kurdish and at the same time attempted to negotiate a ceasefire with the PKK through various channels and means. During his first term in office, he released several political prisoners, including Rıza Altun and Mustafa Karasu, in 1992. However, this was an attempt to send a political message. Altun often made his friends in prison laugh with jokes and humor so, when he first heard his death sentence had been commuted and he would be released, he thought it was a joke. He. When the prison officials read out the decision and his fellow prisoners burst into tears, he realized the seriousness of the situation.

After his surprise release in 1992, Altun quickly left Turkey and went to the recently opened party academy in Damascus, which was headed by Abdullah Öcalan. As a political and historical rival of Turkey, the Syrian government provided space for the party academy for ten years, until it was closed due to pressure from Turkey and the US.

Altun describes this period in the following words: “At that time, our leader Apo (Öcalan) was living in a high-rise building in Aleppo. When we arrived there with Mustafa Karasu, he came down to the entrance and welcomed us with great joy and hugs. He said, ‘It is meaningful to have achieved this.’ After a while, we went together to Damascus to the academy, where we stayed together, discussed, and worked. Karasu later went to Europe as the person in charge, but I stayed there for a long time. I was involved in many activities there, especially diplomatic work, until I went to Iran as the person in charge.” Altun became part of the inner circle—as he had been in the early days in Ankara—and accompanied diplomatic talks on behalf of the movement, including the preparation of the first ceasefire in 1993. He also took part in the Beirut press conference with Öcalan on March 20, in which the PKK (through various intermediaries) sought a political solution with Turkish President Turgut Özal. Özal, who was also striving for a solution, died under mysterious circumstances on April 17, 1993—the very day he was planning to respond to the ceasefire.

A Return to Armed Conflict

This clearly sabotaged efforts to achieve a ceasefire and a political, peaceful solution. In the subsequent power vacuum, Turkey’s political leaders reignited the armed conflict. Turkey and its military were able to gain the upper hand in the conflict with further international NATO support. In exchange for many political, economic, and geostrategic concessions, the PKK’s resistance struggle was criminalized in many countries and demonized as a terrorist organization (first in the US and then in the EU from 2002). The international community viewed the PKK solely through the lens of Turkish nationalism and state doctrine. The truth was distorted beyond recognition by systematic smear campaigns and political propaganda.

Nevertheless, Öcalan and the PKK persisted in their search for contacts in Turkish politics. Öcalan tried with great perseverance to solve the problem by political and peaceful means. When this failed, he even attempted to bring the matter to the international stage. Before he was abducted to Turkey in 1999, he spent months in Europe seeking international support for a political solution.

During this time, Altun could be found wherever the movement needed him: sometimes as a diplomat and representative of the movement in Lebanon, Iran, and Iraq; sometimes as a politician with social responsibility, such as in the establishment of the Makhmour (Kurdish: Mexmûr) refugee camp in Iraq and in European exile; and at other times as an ideological instructor and guerrilla commander in the mountains of Kurdistan.

Inspiring Europe

From 2001 onwards, Altun worked to communicate the ideas of the movement within the Kurdish organizations of Europe. He served as a link between the youth and women’s movements and the organizational structures in exile, giving them ideological and political direction. I attended a seminar in Paris in 2004 and was one of many participants inspired by his lecture. He emphasized how important it is to engage politically against the evil raging everywhere and how crucial it is to set personal impulses. He gave examples from his own life: “Intensive self-education is necessary to develop self-confidence in thinking and acting. Revolutionary individuals who act with self-confidence and are willing to take responsibility can influence processes, no matter how difficult the situation they find themselves in.” He spoke a lot about the resistance in prison, as it had been a turning point in the struggle. Whenever he spoke about Kemal Pir, his admiration was palpable. His eyes sparkled and he described him as a school that had greatly influenced him. As a young journalist, I was fortunate enough to meet Altun several times and ask him many questions. He spoke at length about the history of the movement and its international aspects, which unfortunately received too little attention due to criminalization. I last met him in Europe in 2007, before he returned to the mountains of Kurdistan.

Resistance Everywhere, Against Everything that Wants to Destroy You

For years, I peppered him with questions. In 2015, he described to me how the resistance in Kobanê (against IS/Daesh) embodied the spirit of the movement: “Resistance everywhere, against everything that wants to destroy you, until the very last second and opportunity.” I have met few people who were as socially, politically, and theoretically convincing as he was. That makes him a very special revolutionary and source of hope for me and many others.

He shared this persuasiveness with his closest family. All three of his sisters and four brothers were or are politically active themselves and have also convinced their children to follow suit. His younger brother Haydar (Kara Ömer) was killed in Heftanin in 1991 as a guerrilla commander while Rıza Altun was still in prison. Three of his nephews took part in the liberation struggle as guerrillas, two of whom were killed: Salih Doğan Yıldırım (Cumaali) fell in 2005 in a battle with the Turkish army; and Sinan Altun (Doğan) in 2006 by Iranian artillery.

In response to systematic criminalization by the Turkish state and its allies, the KCK’s Foreign Relations Committee—founded and led by Rıza Altun from 2012—continuously informed the international public and politicians about the movement in Kurdistan. This inevitably prompted a reaction from the Turkish state, which targeted him. Within a year, he was injured in three separate drone strikes before ultimately losing his life to a fourth. He fell in the Qandil Mountains on September 25, 2019.

There is a clear contradiction: on the one hand, international states repeatedly emphasize that they want to uphold human rights. On the other hand, the drones used by the Turkish state were produced with international support. In the first two attacks and others that followed, at least six close associates of Rıza Altun who were actively involved in the committee were killed.

Cemil Bayık is a founding member of the PKK and co-chair of the KCK Executive Council. He was one of Altun’s first associates from Ankara, with whom he collaborated in many areas of the liberation struggle. Bayık emphasized afterwards that the Turkish state believed it would not be good for its murderous policies if Altun and the committee continued their work. That is why he was specifically targeted, because he was trying to raise international awareness of developments in Kurdistan and the movement’s perspective through public relations work. “H. Rıza was a great revolutionary, a great socialist, and a passionate comrade who never let obstacles deter him. (…) He maintained his comradeship with leader Apo (Öcalan) until the day he died a martyr’s death. On this basis, he also maintained an exemplary comradeship with me and, above all, with the friends in the movement. (…) He was my companion, and we fought together. He influenced me. I have taken much from him as a role model and will continue to do so.”

In a similar vein, Duran Kalkan—a member of the KCK Executive Council who had been a companion since the early days in Ankara—described Altun as follows: “In the most difficult circumstances, in places that were considered impossible, he made a great contribution to shaping the course of our struggle with great courage and self-sacrifice, as well as creativity and initiative, and prevailed against all possible opponents.”

The Hevals and Heval Rıza

With his humor and wit, H. Rıza was a revolutionary who knew the depths and difficulties of life, but never lost his zeal for it. , as he tried to protect the beauty of life represented in interpersonal relationships, even when circumstances were difficult. How difficult life as a revolutionary can be needs no further explanation. Rıza Altun said, “You have to stand up to them, and humor is a good way to do that.” He did not make politics strict and unpleasant, but rather joyful, convincing, and creative.

No matter where he was, he was the charismatic and popular Heval Rıza. In Kurdish, ‘Heval’ means “friend” in Kurdish, but it encompasses more than that. In the course of the liberation struggle, the term became synonymous with the tens of thousands of PKK cadres who dedicated their lives to the revolution. Socialists opposed to nationalism, racism, patriarchal forms of society, and especially capitalism, these militants have no interest in material things, carry no money, and own nothing, but their lives are made rich with ideals, ideas, and the motivation to implement them. It is therefore a great credit and tribute when the people who follow them express it this way: “It is not only what they say, but also how they live that convinces us.” Altun’s mother Hatice once said, “When the hevals came to our house, we thought the angels were visiting us.”

The hevals were always there when people living in misery and oppression saw no way out. Tens of thousands lost their lives in order to change conditions and create space for freedom and dignity. During the years of the liberation struggle, the hevals developed their own culture of resistance: an ethical understanding of a free, dignified, and equal life. They try to live this culture and these principles in their everyday lives. H. Rıza was and is an uncompromising pioneer of this new culture of resistance in Kurdistan.

In an interview, H. Rıza explained that he himself was just as surprised as the Turkish state and the world about the success of their struggle: “Back then in Ankara, we couldn’t have imagined today’s developments. Our key concept is resistance. We decided to resist everywhere and against everything that is wrong. This resonated in Kurdistan, where millions of people supported us with all their resources. We carried out a revolution in Kurdistan that included many other revolutionary processes, such as those of women, peoples, and democratic confederalism.”

45 Years of Struggle

At the age of 65, H. Altun fell fighting, the culmination of 45 years of uninterrupted revolutionary struggle and resistance. But this was not a life chosen from mere belligerence or love of violence, nor were his revolutionary acts tied to a specific place. Rather, he fought for and lived a life that transcended the physical world: a flowing life full of love, resistance, and dignity.

If one wants to delve deeper into the history of the hevals and their struggle for liberation in Kurdistan, the life and struggle of H. Rıza is a fascinating starting point. He was a resistance fighter who gave hope to the discouraged people of his era in Kurdistan. He was a wandering guerrilla and resisted when all seemed lost.

He stood up to his opponents wherever he fought. His life, which began with uprooting, ended where it meant the most to him: in the mountains of Kurdistan. And the mountains were not just a symbol for him, but a necessity; they became the place of his highest self-realization: “The mountains give us the opportunity to be truly free. They are not just a place of retreat, they are a prerequisite for our struggle for freedom. For many of us, they have become an indispensable habitat—a way of life.” What he left behind in words, deeds, encounters, and ideas remains. In our hearts, in our consciousness, in our resistance.

He involved his entire family and everyone he came into contact with in the struggle for liberation. He is a great example for people who want to live a “vibrant” life: to love humanity and liberate the oppressed, you need a character like H. Rıza. Wise people are right to say that one cannot take material possessions with them after death; in the end, what is truly valuable is the kind of life a person has lived and what they have left behind in the minds and hearts of others. From this perspective, H. Rıza never cared about material goods. He owned neither a house nor a car nor financial assets, but with his life and work he created an entire culture of resistance in Kurdistan. In this text, I have tried to give readers a little insight into Rıza Altun, whom I had the privilege of knowing and who played an important role in my life. In his eventful life, he continued the tradition of Che Guevara, Ho Chi Minh, Bobby Sands, Rosa Luxemburg, Thomas Sankara, Thomas Müntzer, Sakine Cansiz, Antonio Gramsci, and many, many more.

Revolutionary, Socialist, and Universally Educated Intellectual

Almost 100 years ago, from inside a fascist prison, Antonio Gramsci recorded one of his most important thoughts: “We must create sober, patient people who do not despair in the face of the worst horrors and do not get excited about every stupidity. Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.” According to Gramsci, all people have intellectual abilities, but not all take on the social role of an intellectual. H. Rıza was inspiring and motivating in his life and struggle. With his profound persuasiveness and knowledge, he exerted a great influence on everyone. As a revolutionary, socialist, and universally educated intellectual, H. Rıza performed a tireless social function in the struggle for liberation.

In a detailed interview with the ANF agency in November 2017, he described the international context, its ideology, and its political implementation. In particular, he addressed the socialist perspective, which was crucial to his struggle: “If capitalism can survive today with imperialist policies, it is because the forces of freedom, the socialist forces, are unable to articulate themselves well enough and fail to organize themselves and turn their ideas into a struggle. Just as the capitalist world economic system is controlled from a central point, the forces of freedom must also come together on a democratic basis to form an internationalist unity. Without this, it is unlikely that they will be able to eliminate capitalism and imperialism.“ In his statement, he resolutely emphasized the need for socialist internationalism, describing “a new international” as “urgently needed”.

Life does not allow everyone to live like H. Rıza. Even if one could, not everyone would choose to follow this path. But it is clear from the outset that one who has chosen to live like this shall not die old, sick, and in pain in bed. A life marked by so much movement, emotion, and passion will invariably make one many enemies, and H. Rıza was no different. His enemies persecuted him, constantly monitored him, and repeatedly tried to end his life. His departure came too soon, but a martyr never truly dies. H. Rıza will be a shining example for all those who wish to continue living with dignity and resilience.

Devriş Çimen is a Kurdish journalist and politician.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate