Imperialism has never limited itself solely to military occupations, economic plunder, or diplomatic bullying. Its true power lies in its ability to construct mental and political mechanisms that paralyze the historical will of peoples.

Since the last quarter of the twentieth century, modern capitalist hegemony has centralized a more refined, insidious, and “extralegal but in the name of law” method to overcome the costs and legitimacy crises of classical colonialism: the taking of leaders who represent the hope of freedom as hostages.

This hostage-taking is not merely a physical liquidation; on the contrary, it is a multi layered regime of captivity aimed at targeting collective memory, humiliating collective will, and breaking a people’s self-confidence. In this context, captivity is not a punishment for modern imperialism, but a technique of governance.

The Hegelian master-slave dialectic transcends its classical form here and is carried to a collective plane. The master no longer chains only the individual slave, but also the slave’s capacity to dream, their claim to historical continuity, and their vision for the future.

The captured leader ceases to be a mere body; they become the symbolic carrier of a people’s possible futures. Precisely for this reason, the imperialist mind does not judge these leaders, engage in polemics with them, or attempt to persuade them. It casts them outside the law, abducts them through piracy, criminalizes them, and thereby attempts to declare the political line they represent as illegitimate. Here, the discourse of law, human rights, and democracy turns into an ideological smokescreen covering imperialist violence.

While international law is operated as a set of norms that bind only the weak, lawlessness becomes a strategic privilege for imperialist centers. Abduction, illegal transfer, arbitrary detention, and character assassination are the practical tools of this privilege. Therefore, imperialism does not seek to defeat its rivals; it seeks to “pollute” them morally and politically.

Labels such as “terrorist,” “narco-terrorist,” or “dictator” function as ideological weapons rather than substantive criminal charges. The purpose of these labels is to push all social strata associated with the leader into an indefensible, silenced, and isolated position.

This strategy demonstrates that imperialism acts with a systematic, rather than accidental, logic. Hostage-taking is the most refined form of modern colonialism because it eliminates the need for occupation; it aims to produce surrender without awakening the reflex of resistance that tanks would trigger.

The capture of a leader is a message etched into the collective subconscious: “Look, the will you thought represented you is helpless.” In this respect, hostage operations are not just political but deep psychological warfare techniques.

Precisely at this point, the international conspiracy carried out against Kurdish Leader Abdullah Öcalan on February 15, 1999, should be read as the laboratory of modern imperialism.

This event was not an isolated violation of law, but an open confession of what means the hegemonic system deems legitimate to protect itself. This pirate coalition, led by the CIA and MOSSAD with the involvement of European intelligence services, aimed to take hostage not just an individual, but the Kurdish people’s claim to freedom.

The process stretching from Nairobi to Imrali is the permanentization of a “state of exception” in the sense described by Carl Schmitt. This state of exception reveals who the true sovereign is; the one who holds the power to suspend the law is the actual sovereign.

The February 15 conspiracy showed that the sovereignty of nation-states has long been eroded, and true sovereignty is now concentrated in global intelligence networks and imperialist centers. In this sense, Öcalan’s captivity holds a universal lesson for all oppressed peoples: Imperialism views every thought, every paradigm, and every collective will that produces an alternative to itself as a potential threat and knows no limits in neutralizing this threat.

However, dialectical thought refuses to read this picture as one-sided. Captivity does not always mean absolute defeat. On the contrary, with a correct historical and ideological positioning, it can transform into a new moment of liberation. This is where imperialism’s greatest miscalculation lies. The intellectual production developed by Öcalan under conditions of heavy isolation in Imrali transformed the place of captivity into an arena for a revolution of the mind.

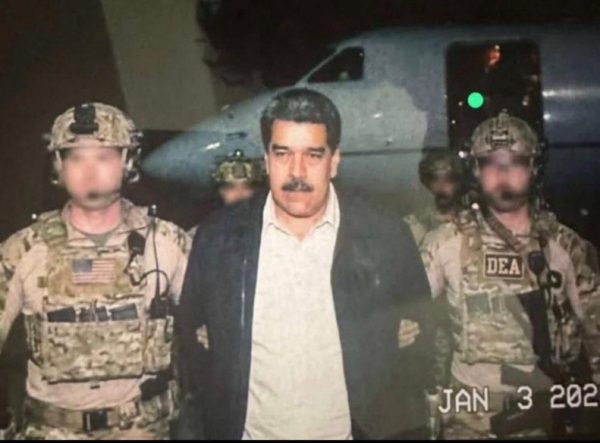

While imperialism chained the body, it failed to calculate the capacity of thought to become socialized. This situation demonstrated that the strategy of hostage-taking is not absolute; rather, it can be neutralized through a revolutionary line. Today, the operation targeting President Maduro and his spouse in Venezuela involving abduction and forced transfer to the USA is a contemporary manifestation of this historical continuity.

This is not an act of personal revenge; it is an attempt to symbolically liquidate a political line in Latin America that refuses to bow to imperialism. US economic sanctions, diplomatic siege, and character assassination have now moved to a more advanced stage: by piratically taking President Maduro hostage, the Bolivarian revolution has been left leaderless.

The similarities here are not coincidental. There is a methodological and ideological continuity between the isolation imposed on Öcalan and the threats directed at Maduro. In both cases, the target is a people’s will to self-determination. In both cases, imperialism attempts to legitimize its own piracy through the discourse of “law.” And in both cases, the fundamental question is: Does a revolution collapse when its leader is taken hostage, or does it enter a new historical phase?

The answer to this question compels us to rethink the relationship between the state, power, society, and freedom. Because the imperialist strategy of hostage-taking is not just an external attack; it is also a litmus test that reveals the internal weaknesses of revolutionary processes. Any revolutionary experiment that is state-centered, bureaucratized, and views the people’s self-organization as secondary becomes excessively dependent on the physical presence of the leader. This dependency makes imperialist conspiracies more effective.

Precisely for this reason, grasping the dialectic of captivity is possible not only by exposing imperialism but by the revolutionary subject reconstructing itself. The international pirate operation of February 15, 1999, should be treated as a threshold that reveals the means by which imperialism reproduces itself, beyond the unlawful detention of a leader.

This event was not just the neutralization of a political actor, but an attempt to suspend the claim of a people to be political subjects on a global scale. The multi national character of the operation was structural, not accidental.

This mechanism showed that nation-state law has been effectively suspended. A leader was captured in a “void” that fell under no country’s jurisdiction and was subsequently imprisoned on an island. This situation points to a plane that transcends Giorgio Agamben’s concept of “bare life.” What is targeted here is not just biological life, but the capacity to produce political meaning.

Imperialist logic preferred to silence and invisibilize Öcalan rather than eliminate his physical existence, hoping to neutralize his intellectual line over time. However, this preference worked contrary to the expected result. Captivity paradoxically laid the ground for thought to break away from material bonds and enter a broader social circulation.

The Imrali process must be evaluated as a phenomenon that transcends the logic of classical prisons. The isolation regime established there was built on the fragmentation of language, contact, and temporality. Yet, the intellectual production developed under these conditions evolved into an axis that redefines the relationship between state, power, and society.

The critique of state-centered liberation strategies, the exposure of the historical limits of the nation-state form, and the conception of social organization as an autonomous sphere are the theoretical outputs of this process. The fundamental error of imperialism lay in the assumption that by taking the leader hostage, the idea could also be taken hostage. Yet, in modern political struggles, an idea cannot be reduced to a body. This contradiction is embodied in the transformation of the Kurdish Freedom Movement.

The classical national liberation perspective centered on seizing the state gave way to an approach based on liberating society. This transformation is not just a tactical adaptation but an ontological break. In this sense, February 15 is not an end, but a beginning. The “decapitation” strategy of imperialism ironically contributed to a political model that is no longer leader-centric.

This situation contains an important lesson on how imperialism can be overcome with its own tools. The strategy of hostage-taking can only be effective if the line

represented by the leader has not been socialized. If an idea remains the property of a narrow cadre or a singular figure, it collapses with captivity. But if the idea has become part of the social fabric, captivity makes it more visible. This lesson’s universal dimension is even more evident in current developments in Latin America.

The siege of Venezuela is a political will-breaking operation. Targeting Maduro is targeting the Bolivarian process itself. However, a critical difference emerges: The paradigm developed by the Kurdish Freedom Movement after February 15 strengthened the social subject by moving the leader’s physical presence away from the center. In Venezuela, the revolutionary process still largely shapes itself around the state apparatus and central power, creating a ground that makes imperialist interventions more effective.

Therefore, the true significance of February 15 is not just a reckoning with the past, but a warning for the present and future. Imperialism changes its methods but not its goals. Freedom depends on the leader’s paradigm taking form in social relations.

The trajectory of aggression against Venezuela reveals that imperialism has never seen Latin America as anything more than a “backyard.” Hugo Chávez’s rise made Venezuela an intolerable deviation for the imperialist system. The pressure concentrated on Maduro is the targeting of the line he represents.

The media, as a strategic apparatus, presents the economic crisis as an internal failure, hiding the impact of sanctions. This discourse prepares the ideological ground for the abduction of a leader as “the establishment of justice.” The methods used are nearly identical to the February 15 conspiracy: intense international defamation, diplomatic isolation, and then a pirate operation in the name of the “international community.” This chain is the hallmark of imperialism.

However, dialectical analysis cannot merely expose external pressure. Imperialist interventions are effective when they connect with internal weaknesses. In Venezuela, the revolution’s reliance on oil revenues and a redistribution model failed to transform production relations in the long run.

The emergence of a new elite, the “Boliburgues a,” has eroded the moral legitimacy of the revolution. This is where the critique of state-centered socialism becomes inevitable. When the state becomes a sacred carrier of revolution, it risks reducing the idea of freedom to technical management.

The critique of state-centered socialism is not to devalue the Bolivarian process, but to move it to a more sustainable line of freedom. Democratic Confederalism, as a paradigm, seeks not to conquer the state, but to transcend it by strengthening local and horizontal relations. This perspective transforms the understanding of leadership; the leader becomes a catalyst for social will rather than an authority that monopolizes it.

The universal dimension of Öcalan’s paradigm is a general freedom strategy against modern power forms. In Venezuela, if the revolution remains a project of the state, it will always be shaken by external intervention.

But if the revolution takes root in neighborhoods, workplaces, and local councils, there is no longer a single center to target. Power becomes stronger as it is decentralized. The duty of revolutionaries is not just to defend Maduro, but to transform the resistance he represents into the daily practice of the people.

International solidarity must also transcend symbolic support. The line drawn between the Middle East and Latin America is a historical necessity. The Kurdish struggle and the Venezuelan resistance must be linked through a common paradigm of freedom. Internationalism is a vital need. Revolutionary action is about creating alternatives and organizing life itself. If this task is undertaken, no CIA-MOSSAD operation or pirate scenario from the USA can stop the march of peoples toward freedom.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate