Another climate summit has mercifully ended. As with past summits, nothing of substance happened. The United States did not participate, meaning that the Trump administration technically could not thwart any attempt to block meaningful decision-making, but that was no problem for the Trump gang as Saudi Arabia was there to pick up the ball.

Any thought as to whether to laugh or cry seems rather quaint, given that environmental concerns were largely absent as is usual practice with these gatherings. Laughing does seem inappropriate. Anger seems a much better option than crying, although the latter is understood.

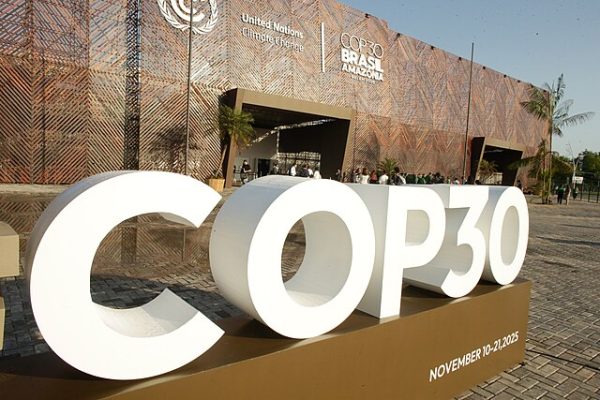

First, however, let us get the climate summit’s final statement out of the way before we work our way through the annual catalog of the vast distance between summit “actions” and what is necessary. Touchingly titling the statement issued at the end of the 30th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (as COP30 is formally known) as “Uniting humanity in a global mobilization against climate change,” the assembled governments “acknowledged” that “climate change is a common concern of humankind,” that everyone possess “the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment” and that the governments should be “emphasizing the importance of conserving, protecting and restoring nature and ecosystems towards achieving the Paris Agreement temperature goal, including through enhanced efforts towards halting and reversing deforestation and forest degradation by 2030 in accordance with Article 5 of the Paris Agreement.” We’ll pause here to note that, under Article 5, the world’s governments “are encouraged to take action to implement and support” agreements reached in 2015, which include holding global warming increases in temperature to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Encouraged, not required.

To return to the COP30 document, there are celebrations of past agreements, more acknowledgements, recalling of past pledges and commendations of previous agreements. The text, for example, “Recognizes the need for urgent action and support for achieving deep, rapid and sustained reductions of greenhouse gas emissions in line with 1.5 °C pathways.” But what actions were taken to implement these ideals? You will search in vain for that. The closest we get is where the text declares it “Decides to convene a high-level ministerial round table to reflect upon the implementation of the new collective quantified goal, including the quantitative and qualitative elements related to the provision of finance.” Well, that will shock governments and fossil fuel companies into action! And I can get you a nice discount on the Brooklyn and Manhattan bridges.

As per usual, lofty goals were set with no enforcement mechanism, with much back-patting for past agreements despite a lack of implementation. After the previous two climate summits were held in countries dependent on fossil fuel extraction, that the just-concluded COP30 was held in the Amazonian city of Belém, Brazil, was supposed to have been symbolic. Of what we might ask, as fossil fuel lobbyists and governments dependent on extracting every drop of their fossil fuels fought the same battles with results similar to past years. Indigenous activists were able to demonstrate at the summit, a change from the past two, but, again, no more than a symbol.

A brief recap of past summits: Last year’s COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, concluded with an agreement that more access to finance, including loans, would be nice and that they will gladly check on the world’s progress in 2030. COP28 in the United Arab Emirates ended with the world’s governments “encouraged” to “transition away” from fossil fuels while promoting finance capital as the savior. COP27 in Egypt ended with “requests” to “revisit and strengthen” 2030 climate targets. Oh please consider stopping your environmental destruction if it’s not too inconvenient. That was preceded by COP26 in Glasgow failing to enact any enforcement mechanisms; COP25 in Madrid concluding with an announcement of two more years of roundtables; COP24 in Katowice, Poland, promoting coal; and COP23 in Bonn ending with a promise that people will get together and talk some more.

Fossil fuel interests again flex their muscles

As last year there was considerable note of the large number of fossil fuel representatives from fossil fuel companies, the solution apparently was to disguise attendees. Transparency International reported that more than half of the “participants in national delegations either did not disclose the type of affiliation they have or selected a vague category such as ‘Guest’ or ‘Other’.” Not that being coy about representation is necessary to achieve the goals of fossil fuel extractors; regardless of the affiliation of individual delegates, Saudi Arabian representatives led a bloc of Arab states in thwarting any attempt to achieve a meaningful conclusion. The United Nations secretary-general, António Guterres, was widely reported to single out Saudi Arabia as the lead obstructor. The Financial Times reported that European officials “also said that Saudi Arabia had been more vehement in stating its positions this year than at previous climate summits.” Perhaps the Saudis felt the need to lobby harder since the Trump gang wouldn’t be there to do some of the dirty work.

Because consensus is necessary to reach decisions at the climate summits, oil-producing countries have an effective veto. A paper issued by the Climate Social Science Network states that Saudi Arabia “has had an outsized role in undermining progress at global climate negotiations, year after year.” The paper notes that “Undermining science is a core strategy employed by Saudi Arabian envoys who contest new climate science at [international gatherings]” and Saudi delegations are led by Riyadh’s Ministry of Energy, which is closely linked with the Saudi state oil company Aramco. Of course, we should have no illusions that the Saudis are lone wolves; they are merely the most energetic at disruption.

The environmental news site DeSmog, for example, reported that the New York public-relations firm Edelman lobbied the Brazilian hosts of COP30 “to choose one of its oil and gas clients to help power the conference, even as it was gearing up to serve as an adviser at the talks aimed at curbing the use of fossil fuels.” Edelman is reported to have a decades-long history of representing ExxonMobil, Shell and Chevron. The PR firm also represents the Brazilian state oil company, Petrobras. Edelman, DeSmog reports, had an $835,000 contract with COP30 organizers. ExxonMobil and Chevron, meanwhile, sent 13 executives to COP30 and ExxonMobil’s chief executive officer, Darren Woods, was a speaker at several side events; in an interview he said crude oil and hydrocarbons were “going to play a critical role in everybody’s life for a long time to come.”

Overall, more than 1,600 fossil fuel lobbyists participated in COP30, DeSmog reports.

They seem to have an effect. One negotiator from an unnamed Global South country, expressing the frustrations of talks going nowhere, said to a Guardian reporter, “Sometimes I feel that this process has lost its humanity. Sometimes it’s like we are arguing with robots. … Just because we do not have money, does not mean we should not be listened to.”

Among those not impressed at COP30’s passing the buck is Harjeet Singh, founding director of the Satat Sampada Climate Foundation in India, who termed the Belém conference as “the deadliest talk show ever.” The “theater of delay” was intended “solely to avoid the actions that matter—committing to a just transition away from fossil fuels and putting money on the table,” he said in an interview with Inside Climate News. Mr. Singh is an advisor to the Fossil Fuel Treaty Initiative, which is an attempt to secure binding agreements to take necessary measures to hold global warming to 1.5 degrees C, in part through banning new coal, oil and gas projects. Thousands of organizations have signed on, as have 18 national governments. Other than Colombia and Pakistan, all the government signatories are small island nations, who know first-hand what a threat global warming is. Unfortunately, no country that is a major contributor to global warming has signed on.

It is not as if there should be no urgency in tackling the problem of global warming and associated environmental issues. An analysis conducted by ProPublica and The Guardian forecast that there will be 1.3 million extra deaths from temperature extremes in the next 80 years if the Trump administration’s policies are continued, with the “vast majority” of these extra deaths outside the United States. The calculations, which are based on several peer-reviewed scientific papers, don’t include indirect deaths to be caused from global warming. The report said, “The estimate reflects deaths from heat-related causes, such as heatstroke and the exacerbation of existing illnesses, minus lives saved by reduced exposure to cold. It does not include the massive number of deaths expected from the broader effects of the climate crisis, such as droughts, floods, wars, vector-borne diseases, hurricanes, wildfires and reduced crop yields.”

The number of extra deaths that could result from all human-caused emissions in the next 80 years if current policies aren’t reversed is 83 million, the report concludes.

The Paris goal is almost out of reach

Future problems from Earth continuing to grow warmer are not limited to the basic matter of higher temperatures and the effects on people unaccustomed to more severe heat. Parts of the Earth’s surface could literally become uninhabitable. As the climate grows hotter, there are places in South Asia and the Middle East that could become so unbearable due to a combination of heat and humidity that the human body would be unable to cool itself off, with exposure to such conditions leading to death in about six hours. There already have been a few instances of such conditions arising, albeit for an hour or two, not long enough for lethality for someone healthy but likely fatal to many. But somewhat less extreme conditions, which will become possible in more areas of the world, could be lethal for all but the healthiest. The limit at which all would die within six hours from extreme heat and humidity could regularly occur in South Asia and the Middle East by the third quarter of the 21st century under present worst-case scenarios, according to three climate scientists who published a report on this possibility.

Although that scenario need not become reality (but would if current trends in greenhouse gases continue), there will be plenty of disasters awaiting. Climate Action Tracker, after each global climate summit, provides a snapshot of where the climate is going. Under the “optimistic” scenario of full implementation of all announced targets, the global temperature will rise 1.9 degrees C. above the pre-industrial average by 2100, and the rise could be as high as 2.4 degrees. In other words, a wide miss of the 1.5 degree Paris goal. Based on current policies, global temperatures will rise by a catastrophic 2.6 degrees, and possibly more than 3. To reiterate, those targets are promises with no mechanism of enforcement.

“Almost none of the 40 governments the [Climate Action Tracker] analyses have updated their 2030 target, which is critical to keep warming levels below 1.5°C, nor have they set out the kind of action in their new 2035 targets that would change the warming outlook,” Climate Action Tracker said in its report. The chief executive officer of Climate Analytics, Bill Hare, added, “The world is running out of time to avoid a dangerous overshoot of the 1.5°C limit. Delayed action has already led to higher cumulative emissions, and new evidence suggests the climate system may be more sensitive than previously thought. Without rapid, deep emissions cuts — over 50% by 2030 — overshooting 1.5°C becomes ever more likely, with severe consequences for people and ecosystems.”

To put some concrete numbers on how much further necessary reductions to greenhouse-gas emissions are needed, Climate Action Tracker reports that emissions are expected to reach 53 to 57 gigatons of emissions by 2030, whereas holding emissions to the level necessary to keep temperatures rising above 1.5 degrees requires a fall to 27 gigatons by 2030 with further cuts beyond that level. A gigaton is 1 million metric tons; a metric ton equals 2.2 times the “short” ton of the imperial weight system used in the United States. “Governments must urgently strengthen or overachieve 2030 targets, implement robust policies, and ensure transparency and accountability,” Climate Action Tracker wrote.

Despite the increasing urgency, carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuels and cement will set a record in 2025. And although the rate of increase of greenhouse-gas emissions is slowing, Earth’s ability to absorb those emissions is declining. Those “carbon sinks” are an estimated 15 percent weaker than they were a decade earlier. The amount of carbon dioxide and equivalents that the atmosphere can take before the 1.5 degree goal is breached is approaching, a Carbon Brief report states. “The remaining carbon budget to limit global warming to 1.5C is virtually exhausted and is equivalent to only four years of current emissions,” Carbon Brief wrote. “Carbon budgets to limit warming to 1.7C and 2C would similarly be used up in 12 and 25 years, respectively.”

The world groans as the wealthy play

That is nothing new. A 2016 report found that even if greenhouse gases had ceased to have been thrown into the atmosphere then, decades of further global warming were likely because the world’s oceans are reaching their capacity to be a carbon sink. This report, a compilation produced by dozens of climate scientists from around the world based on more than 500 peer-reviews papers, found that for the previous four decades, the world’s oceans had absorbed 93 percent of the enhanced heating. But the accumulated heat is not permanently stored; it can be released back into the atmosphere, potentially providing significant feedback that would accelerate global warming. The extra heat absorbed by the oceans raises ocean temperatures, with corresponding bad outcomes for aquatic life and more severe tropical cyclones. Ocean absorption of excess heat, the report said, “happens at the cost of profound alterations to the ocean’s physics and chemistry that lead especially to ocean warming and acidification, and consequently sea-level rise. … The problem is that we know ocean warming is driving change in the ocean — this is well documented — but the consequences of these changes decades down the line are far from clear.”

Let’s get down to specifics. The discussion of global warming has been abstract, as if humanity collectively indulges in suicidal behavior. But “humanity” is not the problem. We live in an economic system, capitalism, that requires continual growth, and that growth means more industrial activity. In turn, that economic system leads to drastically unequal wealth and power. Global South countries contribute little to greenhouse-gas buildups. Global North countries, and now China, contribute in huge amounts. Fossil fuel companies, and the banks that facilitate and invest in their production, contribute massively to greenhouse-gas emissions, and have the world’s governments in their pockets. In the United States, fossil fuel companies literally dictate (although no arm-twisting is necessary) U.S. energy policy under the Trump administration. And those possessing extreme wealth contribute vastly more than even middle-income people, much less the world’s abundant poor.

A recent report put out by Oxfam and the Stockholm Environment Institute found that the world’s wealthiest 0.1% burn carbon at 400 times the rate of the world’s poorest 10%. And that divide is getting bigger — the richest 0.1% increased their carbon footprint by 32 percent since 1990 while the poorest 50% of humanity actually decreased theirs by 3%. The report said:

“The super-rich are not just overconsuming carbon, but also actively investing in and profiting from the most polluting corporations. Oxfam’s research finds that the average billionaire produces 1.9 million tonnes of [carbon dioxide equivalent] a year through their investments. These billionaires would have to circumnavigate the world almost 10,000 times in their private jets to emit this much. Almost 60% of billionaire investments are classified as being in high climate impact sectors such as oil or mining, meaning their investments emit two and a half times more than an average investment in the S&P Global 1,200. The emissions of the investment portfolios of just 308 billionaires total more than the combined emissions of 118 countries.”

How does that translate into real-world effects? The report stated, “The emissions of the richest 1% are enough to cause an estimated 1.3 million heat-related deaths by the end of the century, as well as $44 trillion of economic damage to low- and lower-middle-income countries by 2050.”

Our descendants, living in a world of flooded coastal cities, agricultural disruptions, severe weather outbreaks, massive dislocations and environmental disasters, are not likely to find the ability of a minuscule elite living in the past grabbing massive profits to have been a good tradeoff for the world they will have inherited. Yet another reminder that an economy built for massive accumulation by a tiny elite in a world in which corporations can offload their costs onto the environment rather than an economy built for human need based on sustainability has massive costs.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate