Given the secrecy typically accorded to the military and the inclination of government officials to skew data to satisfy the preferences of those in power, intelligence failures are anything but unusual in this country’s security affairs. In 2003, for instance, President George W. Bush invaded Iraq based on claims — later found to be baseless — that its leader, Saddam Hussein, was developing or already possessed weapons of mass destruction. Similarly, the instant collapse of the Afghan government in August 2021, when the U.S. completed the withdrawal of its forces from that country, came as a shock only because of wildly optimistic intelligence estimates of that government’s strength. Now, the Department of Defense has delivered another massive intelligence failure, this time on China’s future threat to American security.

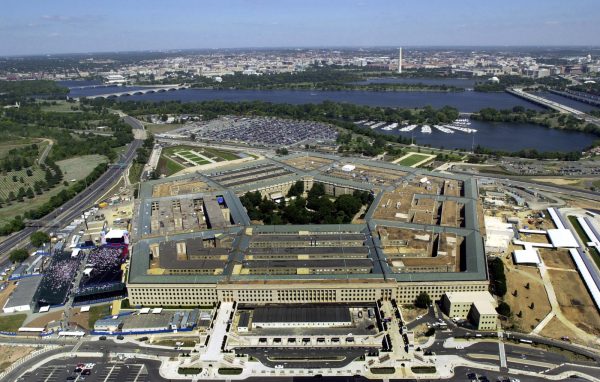

The Pentagon is required by law to provide Congress and the public with an annual report on “military and security developments involving the People’s Republic of China,” or PRC, over the next 20 years. The 2022 version, 196 pages of detailed information published last November 29th, focused on its current and future military threat to the United States. In two decades, so we’re assured, China’s military — the People’s Liberation Army, or PLA — will be superbly equipped to counter Washington should a conflict arise over Taiwan or navigation rights in the South China Sea. But here’s the shocking thing: in those nearly 200 pages of analysis, there wasn’t a single word — not one — devoted to China’s role in what will pose the most pressing threat to our security in the years to come: runaway climate change.

At a time when California has just been battered in a singular fashion by punishing winds and massive rainstorms delivered by a moisture-laden “atmospheric river” flowing over large parts of the state while much of the rest of the country has suffered from severe, often lethal floods, tornadoes, or snowstorms, it should be self-evident that climate change constitutes a vital threat to our security. But those storms, along with the rapacious wildfires and relentless heatwaves experienced in recent summers — not to speak of a 1,200-year record megadrought in the Southwest — represent a mere prelude to what we can expect in the decades to come. By 2042, the nightly news — already saturated with storm-related disasters — could be devoted almost exclusively to such events.

All true, you might say, but what does China have to do with any of this? Why should climate change be included in a Department of Defense report on security developments in relation to the People’s Republic?

There are three reasons why it should not only have been included but given extensive coverage. First, China is now and will remain the world’s leading emitter of climate-altering carbon emissions, with the United States — though historically the greatest emitter — staying in second place. So, any effort to slow the pace of global warming and truly enhance this country’s “security” must involve a strong drive by Beijing to reduce its emissions as well as cooperation in energy decarbonization between the two greatest emitters on this planet. Second, China itself will be subjected to extreme climate-change harm in the years to come, which will severely limit the PRC’s ability to carry out ambitious military plans of the sort described in the 2022 Pentagon report. Finally, by 2042, count on one thing: the American and Chinese armed forces will be devoting most of their resources and attention to disaster relief and recovery, diminishing both their motives and their capacity to go to war with one another.

China’s Outsized Role in the Climate-Change Equation

Global warming, scientists tell us, is caused by the accumulation of “anthropogenic” (human-produced) greenhouse gases (GHGs) in the atmosphere that trap the reflected light from the sun’s radiation. Most of those GHGs are carbon and methane emitted during the production and combustion of fossil fuels (oil, coal, and natural gas); additional GHGs are released through agricultural and industrial processes, especially steel and cement production. To prevent global warming from exceeding 1.5 degrees Celsius above the pre-industrial era — the largest increase scientists believe the planet can absorb without catastrophic outcomes — such emissions will have to be sharply reduced.

Historically speaking, the United States and the European Union (EU) countries have been the largest GHG emitters, responsible for 25% and 22% of cumulative CO2 emissions, respectively. But those countries, and other advanced industrial nations like Canada and Japan, have been taking significant steps to reduce their emissions, including phasing out the use of coal in electricity generation and providing incentives for the purchase of electric vehicles. As a result, their net CO2 emissions have diminished in recent years and are expected to decline further in the decades to come (though they will need to do yet more to keep us below that 1.5-degree warming limit).

China, a relative latecomer to the industrial era, is historically responsible for “only” 13% of cumulative global CO2 emissions. However, in its drive to accelerate its economic growth in recent decades, it has vastly increased its reliance on coal to generate electricity, resulting in ever-greater CO2 emissions. China now accounts for an astonishing 56% of total world coal consumption, which, in turn, largely explains its current dominance among the major carbon emitters. According to the 2022 edition of the International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook, the PRC was responsible for 33% of global CO2 emissions in 2021, compared with 15% for the U.S. and 11% for the EU.

Like most other countries, China has pledged to abide by the Paris Climate Agreement of 2015 and undertake the decarbonization of its economy as part of a worldwide drive to keep global warming within some bounds. As part of that agreement, however, China identified itself as a “developing” country with the option of increasing its fossil-fuel use for 15 years or so before achieving a peak in CO2 emissions in 2030. Barring some surprising set of developments then, the PRC will undoubtedly remain the world’s leading source of CO2 emissions for years to come, suffusing the atmosphere with colossal amounts of carbon dioxide and undergirding a continuing rise in global temperatures.

Yes, the United States, Japan, and the EU countries should indeed do more to reduce their emissions, but they’re already on a downward trajectory and an even more rapid decline will not be enough to offset China’s colossal CO2 output. Put differently, those Chinese emissions — estimated by the IEA at 12 billion metric tons annually — represent at least as great a threat to U.S. security as the multitude of tanks, planes, ships, and missiles enumerated in the Pentagon’s 2022 report on security developments in the PRC. That means they will require the close attention of American policymakers if we are to escape the most severe impacts of climate change.

China’s Vulnerability to Climate Change

Along with detailed information on China’s outsized contribution to the greenhouse effect, any thorough report on security developments involving the PRC should have included an assessment of that country’s vulnerability to climate change. It should have laid out just how global warming might, in the future, affect its ability to marshal resources for a demanding, high-cost military competition with the United States.

In the coming decades, like the U.S. and other continental-scale countries, China will suffer severely from the multiple impacts of rising world temperatures, including extreme storm damage, prolonged droughts and heatwaves, catastrophic flooding, and rising seas. Worse yet, the PRC has several distinctive features that will leave it especially vulnerable to global warming, including a heavily-populated eastern seaboard exposed to rising sea levels and increasingly powerful typhoons; a vast interior, parts of which, already significantly dry, will be prone to full-scale desertification; and a vital river system that relies on unpredictable rainfall and increasingly imperiled glacial runoff. As warming advances and China experiences an ever-increasing climate assault, its social, economic, and political institutions, including the ruling Chinese Communist Party (CCP), will be severely tested.

According to a recent study from the Center for Climate and Security, “China’s Climate Security Vulnerabilities,” the threats to its vital institutions will take two major forms: hits to its critical infrastructure like port facilities, military bases, transportation hubs, and low-lying urban centers along China’s heavily populated coastline; and the danger of growing internal instability arising from ever-increasing economic dislocation, food scarcity, and governmental incapacitation.

China’s coastline already suffers heavy flooding during severe storms and significant parts of it could be entirely underwater by the second half of this century, requiring the possible relocation of hundreds of millions of people and the reconstruction of billions of dollars’ worth of vital facilities. Such tasks will surely require the full attention of Chinese authorities as well as the extensive homebound commitment of military resources, leaving little capacity for foreign adventures. Why, you might wonder, is there not a single sentence about this in the Pentagon’s assessment of future Chinese capabilities?

Even more worrisome, from Beijing’s perspective, is the possible effect of climate change on the country’s internal stability. “Climate change impacts are likely to threaten China’s economic growth, its food and water security, and its efforts at poverty eradication,” the climate center’s study suggests (but the Pentagon report doesn’t mention). Such developments will, in turn, “likely increase the country’s vulnerability to political instability, as climate change undermines the government’s ability to meet its citizens’ demands.”

Of particular concern, the report suggests, is global warming’s dire threat to food security. China, it notes, must feed approximately 20% of the world’s population while occupying only 12% of its arable land, much of which is vulnerable to drought, flooding, extreme heat, and other disastrous climate impacts. As food and water supplies dwindle, Beijing could face popular unrest, even revolt, in food-scarce areas of the country, especially if the government fails to respond adequately. This, no doubt, will compel the CCP to deploy its armed forces nationwide to maintain order, leaving ever fewer of them available for other military purposes — another possibility absent from the Pentagon’s assessment.

Of course, in the years to come, the U.S., too, will feel the ever more severe impacts of climate change and may itself no longer be in a position to fight wars in distant lands — a consideration also completely absent from the Pentagon report.

The Prospects for Climate Cooperation

Along with gauging China’s military capabilities, that annual report is required by law to consider “United States-China engagement and cooperation on security matters… including through United States-China military-to-military contacts.” And indeed, the 2022 version does note that Washington interprets such “engagement” as involving joint efforts to avert accidental or inadvertent conflict by participating in high-level Pentagon-PLA crisis-management arrangements, including what’s known as the Crisis Communications Working Group. “Recurring exchanges [like these],” the report affirms, “serve as regularized mechanisms for dialogue to advance priorities related to crisis prevention and management.”

Any effort aimed at preventing conflict between the two countries is certainly a worthy endeavor. But the report also assumes that such military friction is now inevitable and the most that can be hoped for is to prevent World War III from being ignited. However, given all we’ve already learned about the climate threat to both China and the United States, isn’t it time to move beyond mere conflict avoidance to more collaborative efforts, military and otherwise, aimed at reducing our mutual climate vulnerabilities?

At the moment, sadly enough, such relations sound far-fetched indeed. But it shouldn’t be so. After all, the Department of Defense has already designated climate change a vital threat to national security and has indeed called for cooperative efforts between American forces and those of other countries in overcoming climate-related dangers. “We will elevate climate as a national security priority,” Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin declared in March 2021, “integrating climate considerations into the Department’s policies, strategies, and partner engagements.”

The Pentagon provided further information on such “partner engagements” in a 2021 report on the military’s vulnerabilities to climate change. “There are many ways for the Department to integrate climate considerations into international partner engagements,” that report affirmed, “including supporting interagency diplomacy and development initiatives in partner nations [and] sharing best practices.” One such effort, it noted, is the Pacific Environmental Security Partnership, a network of climate specialists from that region who meet annually at the Pentagon-sponsored Pacific Environmental Security Forum.

At present, China is not among the nations involved in that or other Pentagon-sponsored climate initiatives. Yet, as both countries experience increasingly severe impacts from rising global temperatures and their militaries are forced to devote ever more time and resources to disaster relief, information-sharing on climate-response “best practices” will make so much more sense than girding for war over Taiwan or small uninhabited islands in the East and South China Seas (some of which will be completely underwater by century’s end). Indeed, the Pentagon and the PLA are more alike in facing the climate challenge than most of the world’s military forces and so it should be in both countries’ mutual interests to promote cooperation in the ultimate critical area for any country in this era of ours.

Consider it a form of twenty-first-century madness, then, that a Pentagon report on the U.S. and China can’t even conceive of such a possibility. Given China’s increasingly significant role in world affairs, Congress should require an annual Pentagon report on all relevant military and security developments involving the PRC. Count on one thing: in the future, one devoted exclusively to analyzing what still passes for “military” developments and lacking any discussion of climate change will seem like an all-too-grim joke. The world deserves better going forward if we are to survive the coming climate onslaught.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate