The plan was to stand outside the Houses of Parliament on Guy Fawkes Day with a large inflatable bomb. The protesters would then leaflet MPs as they arrived for Prime Minister’s Questions. But on the day, the far-right put a stop to that. Their larger and far more rowdy protest started earlier, and swamped the allocated space.

The large public square opposite was cordoned off to protect the grass, so the 50 mostly elderly climate protesters had to line a narrow strip of pavement across the road. They stood stoically with their cartoon-styled bomb, eschewing chants and placards to focus attention on their black t-shirts that said ‘Defuse the AMOC bomb’. A few meters away, 100 men wielding Union Jack flags screamed abuse about Kier Starmer into megaphones, let off bangers, and ended up surrounded by police.

The MPs, understandably, avoided this route into Parliament. And while the tourists chose to stream past the more orderly AMOC protest, and politely accepted their explanatory leaflets, all eyes were on the other protest across the road. Despite the bomb, the far right had stolen the limelight.

The scene encapsulated a terrible oversight happening in today’s Britain. The government and media are so set on placating the increasingly popular far-right, and regurgitating their narrative that immigration is the premier threat to this country, that a genuine existential threat – one that has the potential to make the UK largely uninhabitable within a generation – is being overlooked. The AMOC bomb is ticking.

London temperatures could reach -20°C

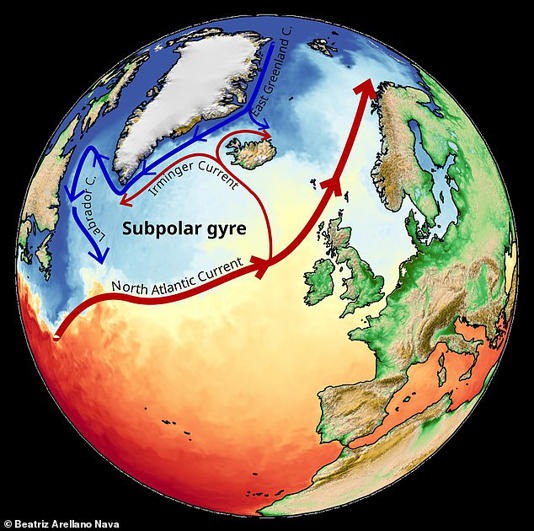

AMOC stands for Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation. It’s a vast cycle of ocean currents that draw heat from the tropics and release it in the North Atlantic. If you’ve ever wondered why Canada has polar bears at roughly the same latitude that England has parakeets, the AMOC is your answer. The problem is that climate change is slowing it down. The AMOC requires salty seawater to drive its heat exchange, but the Atlantic is being flooded by freshwater from Greenland’s melting ice sheets. As the salt content dilutes, the AMOC weakens, and at some point it could become so weak that it will irreversibly shut down.

Scientists have known for decades that the AMOC is slowing down. But it is only in the last few years that the chance of it grinding to a halt has gone from an unlikely event in the 22nd century, to something that might start happening in the next decade or two. The AMOC is extremely complex, and modelling it accurately has proven a huge challenge, meaning predictions by scientists in this field are broad and laden with caveats. But what is clear is that the AMOC problem has been badly underestimated by earlier climate models, including those used by the IPCC, whose reports define climate change risks for the political class.

While researching this article, I am told quite matter-of-factly by Professor Tim Lenton, one of the UK’s leading climate scientists, that the tipping point for AMOC shutdown might already have passed. The AMOC is so vast that it could take another decade for initial impacts to be felt, and half a century for it to finally stop. We could all be sitting in a plane that’s run out of fuel but, for now, glides through the sky untroubled.

If the AMOC does shut down, it will be a global event. Scientists predict an ocean swell that would flood the entire Eastern coast of the United States, and a disastrous disruption of tropical monsoons. But in Northern Europe, particularly for Nordic countries and the UK, the results would be cataclysmic. The region would be plagued by long freezing winters. In Oslo, Norway, temperatures could plummet to -48°C. In London, temperatures could reach -20°C. Our infrastructure and our nature are not built for such conditions. Crop growing would be effectively over in the UK, and face extreme stresses beyond it. Food prices would skyrocket. It’s hard to see how much of Britain could feed itself.

Complicating matters further is the fact that the AMOC is a network of currents that are unlikely to collapse in unison. The component expected to collapse first is the North Atlantic subpolar gyre (SPG), which arcs past Scotland, Iceland and Greenland. While less severe than a full AMOC shutdown, an SPG collapse could still cause major disruption to the UK, and accelerate the collapse of the rest of the AMOC. According to the latest modelling, the chances of this happening are scarily high. There is a 45% chance that an SPG collapse could happen as early as 2040.

Another important facet of the AMOC issue is that solutions are limited. For Northern Europe, adapting to such weather extremes is unrealistic. Geo-engineering the problem would involve dropping millions of kilograms of salt into the North Atlantic every second, which is not feasible. The only way to actively avoid disaster is to reduce carbon emissions as broadly and urgently as possible.

Over the last year and a half, climate scientists, researchers and activists have tried to make the UK and Nordic governments confront this terrifying new AMOC reality. Presentations have been given, letters have been passed, ministerial questions have been asked, and protests have been held. The results have been mixed. Iceland recently designated AMOC collapse both a national security concern and an existential threat, meaning its government is now on alert and assessing what further action is needed. The UK government has chosen a different path.

In October, UK intelligence chiefs were due to launch a report detailing how the country’s security, economy, and food supplies were under severe and imminent threat from the climate crisis. But it was reportedly blocked at the last minute by the Prime Minister’s office. This could optimistically be read as a sign that AMOC collapse is being taken seriously behind closed doors to avoid panic. But the government’s attitude towards reducing carbon emissions suggests otherwise. Last month, it relaxed restrictions on drilling new oil and gas in the North Sea, and selected its preferred plan for expanding Heathrow Airport. These decisions carry vast carbon footprints that will further tip the balance towards AMOC collapse.

With uncanny timing, last month also saw the publication of an inquiry into the then-UK government’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic. The damning report highlighted how the slow decision-making, incoherent messaging, and scientific ignorance of politicians resulted in a pandemic response that was too little, too late, and meant that tens of thousands of lives were needlessly lost. Could the UK government really be flying blind into yet another national crisis, one that utterly dwarfs the pandemic in potential severity?

Worst case scenarios are brushed aside

In 2023, the researcher Laurie Laybourn led a project to understand how people in the UK government understood the threat of climate change, and specifically climate tipping points like AMOC collapse. He and his team, which included Professor Lenton, spoke to people across the civil service, including members of the cabinet office, the environment and defence ministries, and the security services.

“Their understanding of climate change was actually quite limited,” remembered Laybourn. “They thought it would evolve smoothly, and its consequences would be largely things that we often see on the news, like storms and heat waves. But tipping points like AMOC collapse show us that climate change… could be very chaotic and evolve very quickly. And that the consequences are not just the immediate, but also the domino effects which come after some of these disasters happen.”

Laybourn was keen to clarify that this limited mindset was not universal. The parts of government working directly around climate science were well aware of the threat of tipping points. The misconceptions were found in “the community that has to make decisions on major security issues.” For Laybourn and Lenton, the problem largely stems from how tipping points are communicated to politicians – using a scientific framing that can downplay risks and allow worst case scenarios to be brushed aside.

A case in point – the last time the government was asked about AMOC collapse, in 2024, a minister said it had played no part in their economic planning and that a collapse this century was “unlikely.” He was parroting the language of the last IPCC report, but in that context, “unlikely” has a specific probability range attached to it – between 0% and 33%. The minister had unwittingly inferred that there was up to a one-in-three chance that the UK could starve this century, and the government was ignoring it. But neither he nor the Lords listening had realised it.

In comparison, prior to COVID-19, the government considered an influenza pandemic the most pressing civil emergency risk facing the UK. This had a likelihood of just 3% in any given year, but was lavished with risk assessments, early warning systems, governance strategies, and cross-government exercises.

Laybourn and his team wrote a report on their findings – The Security Blind Spot – which concluded that the government was consistently and significantly underestimating security threats resulting from climate change. The authors noted worrying similarities to the situation prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. They urged the government to make climate change a core part of national security planning, and undertake a rapid risk assessment to identify the most critical threats.

One year on from the report’s publication, Laybourn is still waiting to see changes in the government’s approach. He views the recent block by Number 10 of a climate security report as a sign that “short term political considerations are getting in the way,” and references the testimony of Chris Witty, the government’s Chief Medical Adviser, during the COVID-19 inquiry. “Whitty said that ‘non-hostile threats’ are not taken as seriously, culturally, and particularly politically, as the more hostile threats like Russia or China. And I think that culture still clearly prevails.”

Laybourn is particularly dismayed by the lack of studies on SPG collapse, which he believes could plausibly start in the next 10 years, and usher in British winters like the abnormally severe one in 1962/63. This caused 90,000 excess deaths, disrupted food and water supplies, and nearly wiped out certain bird populations. “We have some academic papers on what could happen to the climate system, but we don’t have a decision-useful risk assessment,” he said. “That’s the equivalent of… focusing purely on the epidemiology of how the pandemic could spread, and nothing about what it would mean for mortality or other things like that.”

Lenton notes that ARIA, the government’s new research funding agency, recently launched a program to develop an early warning system for climate tipping points, but is still frustrated by the lack of public money going into AMOC research. “You want to have some bright people work through scenarios of how [AMOC collapse] could interact and cascade across society,” he said. “Nobody’s been doing that, is the short version. Or we’re only just starting to, with minimal trust foundation kind of financial support – no public money, or nothing substantive, which is a bit odd.”

Having just attended the Climate Financial Risk Forum, a yearly event co-organised by the Bank of England, Lenton is more confident that the financial sector gets it. “They’re not stupid. They can see a serious reevaluation of assets downwards, and don’t want to be caught in that again after the crisis of 2007,” he said. “A lot of real estate assets in and around the UK would radically decline in value, and somebody holds that asset… often major pension funds.”

When I mention to Lenton that I’ve had problems sleeping while researching this article, he empathises, and later notes how a lot of climate scientists he knows are equally troubled. He paraphrases Greta Thunberg: instead of worrying about the future, try to change it. For Lenton, that means not waiting for the government to get its act together. “I don’t believe that the government is the most important or only actor,” he said. “They’re a very important one. But the transformative change that we need won’t come about just by waiting for the top-down to suddenly make it happen. That’s not the nature of social change. You need a groundswell, you need a bottom up movement. You need some kind of reinforcing feedback between the bottom-up movement and the top-down. And we’ve had that at times, but we could do with more of it at the moment, that’s for sure.”

The government appear to be frightened

The protest outside parliament was the fifth and final AMOC bomb themed protest organised by Jon Fuller, a veteran climate activist and retired civil servant. He remembered first reading about AMOC collapse a decade ago, in an ICC report which presented the threat as “very unlikely” to happen this century. “I didn’t pay too much attention to it,” he recalled. “But it always struck me as immoral, this idea that there was a catastrophe that could happen further down the line, but because it wasn’t going to impact people currently living on the planet, we could all ignore it.”

When climate scientists started going public late last year with concerns that a collapse could be much more imminent, Fuller wrote to the heads of MI5, MI6, the civil service, and the London Assembly, warning them that they might one day be held accountable in a court of law for their failure to act. Only MI5 responded, to say Fuller didn’t understand their mandate. He replied that they didn’t understand, and that AMOC collapse was an unprecedented national security threat that could kill millions of British citizens. “I didn’t get a reply to that second letter,” said Fuller.

Fuller believed the scale of the disaster now being posited could be a social tipping point for climate action, and pooled interested activists into a WhatsApp group to share ideas on how to amplify awareness of the AMOC threat. The collective decision was to draw in the mainstream media, which had barely covered the issue. This could generate the public pressure needed to make politicians act. The idea of a giant inflatable AMOC bomb (that needed defusing) was born.

But despite laying their bomb outside the Ministry of Defence, City Hall, BBC Broadcasting House, ITN (the home of ITV, Channel 4 and Channel 5) and the Houses of Parliament, media coverage of the protests and AMOC collapse itself has been almost non-existent. For now, the protesters have gone back to the drawing board, and are liaising with members of Scientist Rebellion on how to evolve their campaign.

Asked to explain the silence, Fuller points to the media executives and press barons, keen to stifle awareness about the climate crisis so they can retain their luxury lifestyles. But when it comes to the government’s silence, he puts it down to simple cowardice in the face of a resurgent far-right. “Across Europe, hard-right political parties are pretending climate change isn’t real, it’s not happening, and we don’t have to do anything about it,” he said. “The Labour government appears to be frightened of talking too much about climate change, for fear of playing into the hands of Nigel Farage and his hard-right wing party here in the UK.”

I approached three ministries and multiple members of the National Security Strategy Committee to clarify the UK government’s perspective on AMOC collapse. My interview requests and written questions were blanked or politely declined. The Cabinet Office got in touch to ask who I was writing for and linked me to a short report from 2021 on how the Ministry of Defence planned to be net-zero by 2050. It made no mention of the AMOC, its potential collapse, or any climate tipping points at all.

A spokesperson for the Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) referenced government support for research into climate risks by the Met Office and ARIA. Both the DSIT spokesperson and the Cabinet Office referenced the IPCC 6th Assessment Report from 2021 that said an abrupt collapse of the AMOC is unlikely during the 21st Century. At no point did the government address the change in scientific consensus since 2021, or explain how it will respond to the growing threat.

Meanwhile, the AMOC bomb keeps ticking…

Learn more about AMOC collapse and get involved with raising the alarm.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate

No Comments

The flaw in this otherwise excellent piece is that the ruling elites can somehow be convinced by scientific evidence. Upton Sinclair’s famous observation that “It Is Difficult to Get a Man to Understand Something When His Salary Depends Upon His Not Understanding It” applies to the entire political class in Britain, as does to the global elites across the capitalist world. Hence their retreat into varying iterations of climate denialism, from outright dismissal of the science to willful obfuscation. As Naomi Klein made clear in her book on the climate emergency, This Makes All the Difference, for the propertied elites, recognizing the climate emergency is tantamount to admitting that the intellectual framework withn which they understand social reality is outdated and flawed: that the market can’t be tweaked to solve the very problems that it is causing and that therefore fundamental change is the only solution. As the members of Science Rebellion have been forced to recognize, that fundaental change can only come from the grassroots. That’s why these same elites – well served by the Starmer’s so-called Labour government – are imposing increasingly draconian punishments – including long prison terms for even symbolic protests – on the climate and other citizen’s movements that challenge the the status quo.

Political trends are the most critical part of the climate feedback loop – I’ll explain: As the earth warms, causing violent weather events and desertification, more people from the global south become “climate refugees.” These refugees become scapegoats for growing fascist movements who strive to convince the masses that immigrants rather than capitalists cause their misery. Fascists, in most instances, benefit from oil industry profits which fund right wing think tanks and bankroll campaigns. This leads to more greenhouse gasses as regulations are abandoned. The increased warming creates more refugees, more far right propaganda and more deregulation. And on and on…..

Why does none of this article feel surprising. Governments are failing to deal with the key challenges for the future of species. We have no one in the political classes that has anywhere near the vision or the guts to make the big decisions.

Also, if there are shutdowns in SPG and/or AMOC, how does that affect current climate models, what is the impact on the rest of the globe, negative or positive? Will it mean a worsening, or will it offset some of the nearer term issues for the rest of the planet’s climate?

There is one political leader with the necessary vision and guts: Zack Polanski. He gets the problems: he’s been arrested at climate protests. He’s taking on Reform and the Red/Blue Uniparty. The Greens are polling higher and higher. We just need to get Greens elected!

What about Roger Hallam and his organization’s support for the newly formed new Left, Your Party? And given the dire circumstances that we all face – Canada where I reside experienced massive wildfires last spring, summer & fall from coast to coast to coast, releasing such high levels of GHGs that our so-called climate targets were made meaningless – isn’t it long past the time for the Left to form strategic alliances to stop the capital-driven megamachine that spells our collective doom?

What about Roger Hallam and his organization’s support for the newly formed new Left, Your Party? And given the dire circumstances that we all face – Canada where I reside experienced massive wildfires last spring, summer & fall from coast to coast to coast, releasing such high levels of GHGs that our so-called climate targets were made meaningless – isn’t it long past the time for the Left to form strategic alliances to stop the capital-driven megamachine that spells our collective doom?