The devastating armed conflict in Sudan is the latest iteration, and brutal culmination, of a long history of violence as a mode of governance. Since the coup of the al-Bashir regime in June 1989, if not before, developments in Sudan have been marked by serious human rights and humanitarian law violations in the context of multiple wars, particularly in Darfur, and authoritarian rule. The current war has brought a new country-wide dimension and large-scale victimisation. Available evidence demonstrates that both warring parties have engaged, and continue to engage, in conduct amounting to war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Engagement with transitional justice and the persistence of impunity in Sudan

Sudanese civil society actors have over the last four decades documented and opposed violations and demanded justice. Regional and international engagement on the human rights situation in Sudan dates back to the 1990s. However, it was the report of the United Nations International Commission of Inquiry on Darfur and the referral of the Darfur situation to the prosecutor of the International Criminal Court in 2005 which provided a distinctive impetus for subsequent initiatives on accountability and justice. This included, notably, the report of the 2009 African Union High-Level Panel on Darfur, which set out options for justice based on a series of in-country consultations. These developments stimulated debates and activities on ‘transitional justice’ in Sudan. This applies particularly to the recognition, albeit without effective implementation, of democratic transformation and justice in several peace agreements, from the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement, to the 2006 Abuja agreement and the 2011 Doha Document for Peace in Darfur, and the 2020 Juba Peace Agreement. It also meant that transitional justice became a key element of the transitional period following the 2018–19 revolution. Efforts to dismantle the previous regime and to hold the perpetrators of the June 2019 massacre in Khartoum to account threatened the military-security complex which struck back by staging the October 2021 coup.

The coup ensured that impunity remains the default response to serious violations in Sudan. Its outcome was stark. It frustrated the revolutionary calls for ‘freedom, peace, justice’. It perpetuated power asymmetries and reinstated rule by ‘practitioners of violence’. And it ultimately resulted in a war that is both counter-revolutionary and characterised by in-fighting over the spoils of the country, with significant, frequently problematic external interests and involvement.

The question of justice and accountability in the ongoing war

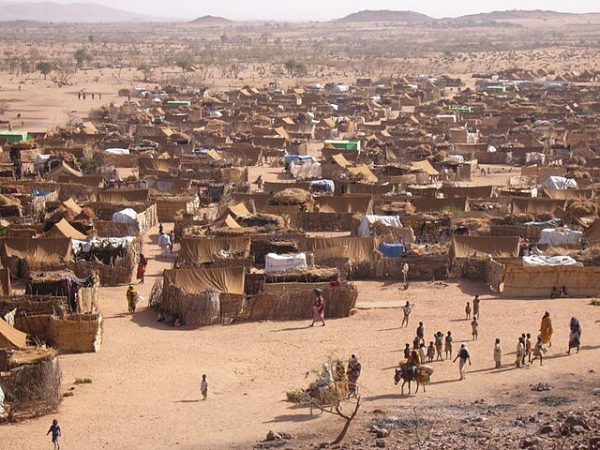

In the current circumstances, the main policy objective is to stop the violence and address the dire humanitarian situation, including of those forcibly displaced within Sudan and across the borders. Yet, the question of justice and accountability looms large. Numerous consultations and deliberations by Sudanese civil society actors have emphasised the importance of establishing accountability as a prerequisite for a more peaceful Sudan and of recognising and prioritising victims. Regional and international human rights bodies, especially the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission for the Sudan, have been documenting violations and calling on Sudanese and international actors to take measures with a view to ensuring justice and accountability.

Urgent assistance and reparation for violations committed during the war, if not prior to it since 1989, is a right of victims whose recognition is pivotal in any forthcoming transition. Their material scope is enormous, from reparation for violations such as sexual violence, arbitrary detention and torture, extrajudicial killings, the destruction of livelihoods, the plundering of property, to the forced displacement of and genocidal attacks on communities. Reparation also entails establishing what happened to missing, often forcibly disappeared persons, including a large number of women and girls. Compensation, rehabilitation, acknowledgment and apologies are important victim-focused components. In addition, accountability measures and a series of legislative, institutional and governance reforms are critical to prevent the recurrence of violations. This applies particularly to security sector reform in Sudan.

Likely scenarios ending the war and the challenges for transitional justice

Discussing these questions is neither academic nor premature. A key lesson from the brief window available for transitional justice measures in Sudan from 2019 to 2021 is the need for civil society actors, including politicians, to be prepared. Their task is to avoid, or at least better navigate, the pitfalls of seeking to advance accountability and justice in politically fragile environments. In the present context, this challenge calls for a politically astute analysis of scenarios for a transition from war to ‘peace’ and their implications for the prospect of justice in Sudan.

Notwithstanding several lacklustre and ineffective efforts to date, a peace process remains one pathway for ending the war. Yet, its suitability as a vehicle for transitional justice is questionable. Previous peace agreements have paid lip-service to questions of justice while focusing on sharing power and wealth. Instead of ushering in a positive peace, they have rewarded violent actors and frequently ignited further violence. Any mediators working on peace in Sudan should therefore focus on a ceasefire agreement first. The warring parties have no legitimacy and should not be rewarded by being given a role in determining substantive questions, especially those that allow them to influence or even partake in Sudan’s future politics. The Joint Statement on Restoring Peace and Security in Sudan adopts, in principle, the right approach by focusing on securing a ceasefire, followed by ‘an inclusive and transparent transition process … towards smoothly establishing an independent, civilian-led government with broad based legitimacy and accountability’. However, the lack of reference to justice and democracy, and emphasis on stability, displays a rather problematic, security-driven agenda pursued by the authors of the statement (the Quad: Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States of America).

Another scenario is the risk of an enduring de facto partition of Sudan. Both parties reportedly continue to be responsible for serious human rights violations. It is therefore highly likely that any ‘transitional justice’ efforts by them within their respective sphere of power will resemble the ‘shadow’ versions of politically manipulated processes the al-Bashir regime had become known for. In addition, current efforts to hold perpetrators of crimes to account, such as by the Sudanese Armed Forces, are reportedly such, in terms of arbitrary detentions, lack of due process, torture and other violations, that they add to the problem rather than help address it.

Transitional justice presupposes a willingness to address past violations, and ideally, by being ‘transformative’ of their political, social, economic and environmental causes. There is ample evidence of such willingness amongst Sudanese civil society actors. What is needed, therefore, is to have processes that are democratic, participatory and led by civilians. Such processes can provide the right political and institutional framework and conditions. However, the difficulty of implementing them with the military-security complex still in place, internal wrangling, problematic mechanisms and numerous other factors seriously hampered efforts towards justice during the 2019–21 transition. Even if there were to be a pathway towards democratic, civilian rule in Sudan, the challenges for political actors to address the multiple dimensions of truth, reparation, accountability and guarantees of non-repetition will be enormous. Facing them requires a concerted political effort and the implementation of carefully designed democratically legitimated processes and mechanisms.

The role of Sudanese actors and their experience in engaging on issues of peace, justice and wider reforms is pivotal in charting the path towards these processes. International actors have had a mixed record on Sudan. The international community so-called has largely failed to take meaningful action to prevent the current war, bring it to a halt, alleviate the humanitarian suffering, or significantly advance the prospect of justice. This must not be the case. A good starting point would be for the African Union to make Sudan a priority for the implementation of its recently adopted Transitional Justice Policy, so that the country can become part of an ‘integrated, prosperous and peaceful Africa’.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate