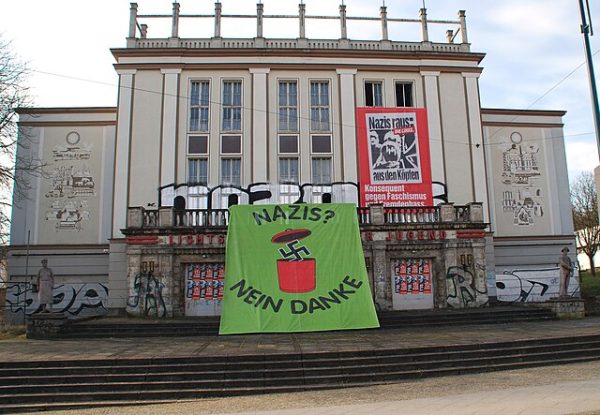

In Germany’s recent election – held in February 2025 – the AfD managed to become the second-strongest political force, winning 21%. Four years earlier, the neo-fascist party’s share had been 10.4%.

In East Germany, it even reached 32%. The AfD thus succeeded in doubling its share of the vote. Worse, this is not because fewer people went to the polls. On the contrary. Voter turnout increased from 76.4% (2021) to 82.5% (2025) – the highest since 1987, almost 40 years ago.

As a result, the AfD won 10.33 million votes compared to 4.81 million in the previous election. There are specific groups within Germany’s population – workers? – in which the AfD has been particularly successful. The neo-fascist AfD has – seemingly – also managed to penetrate new groups of voters.

In geographical terms, the AfD gained particularly in those regions where it was already strongly anchored. In these regions, it received significantly more votes than in the past.

Worse still, the AfD has reached certain demographic groups it had previously struggled to access – especially young voters.

It is striking that there was a particularly high proportion of AfD voters among workers. In addition, the AfD gained especially in regions with a high proportion of industrial jobs. Accordingly, various aspects of the world of work have become politically significant.

Meanwhile, the role of the AfD’s core issue – migration – remains imperative. For the party and its supporters, limiting immigration is of great importance, despite immigration underpinning Germany’s economy in times of acute skill shortages.

Yet AfD voters and party apparatchiks hold negative attitudes toward immigrants. Worse, there is an increasing normalization of far-right attitudes, xenophobic ideologies, and racism. On top of that, there is a broader shift to the right within Germany’s general population.

Maintaining the so-called “firewall” – the refusal of democratic parties to cooperate or merge with the AfD – distinguishes AfD voters (in favour of ending it) from non-AfD voters (against). Despite the AfD’s success in the 2025 federal election and in three East German state elections, many still support excluding the AfD from government participation.

However, the fact that the firewall is visibly crumbling amid the rightward shift of Germany’s conservative parties – for example on migration – is deeply concerning.

An inglorious climax of this rightward trend came on 29 January 2025, when the millionaire, private-jet-flying conservative chancellor Merz (CDU) voted together with the AfD to secure a majority for further tightening Germany’s already restrictive migration policy in parliament.

In other words, German conservatives broke – as they did in 1933 – the “cordon sanitaire” of non-cooperation with the neo-fascist AfD in order to pass anti-migration legislation. Apart from the immediate effect of legitimizing the AfD, such a move has three additional problems:

- The Trap: Falling into the propaganda trap laid by Germany’s neo-Nazis by adopting their issues – anti-migration, xenophobia, racism – will not win voters back. Voters prefer the original (the AfD), not the copy (the conservatives).

- The Original: There is more or less conclusive evidence from other European countries showing that when conservatives adopt neo-Nazi issues, it strengthens the original rather than the copy.

- The Issues: Rather than trying to outrun neo-Nazis on their terrain, conservatives would be far better off emphasizing their own issues: conserving nature, economic stability, social order.

Instead, the AfD has succeeded in placing migration at the centre of political debate and in pushing democratic parties into attempting to “out-Nazi” the neo-Nazis – a strategy that is failing. Whatever German conservatives do, they will never be the better neo-Nazis.

When democratic parties compete with one another over tightening asylum law, thereby adopting neo-Nazi rhetoric and right-wing ideology, their positions become indistinguishable from those of the AfD. The AfD wins.

Copying the neo-fascist AfD by adopting neo-Nazi positions does not weaken the extreme right. On the contrary, it upgrades, legitimizes, normalizes, and ultimately strengthens it electorally.

Democratic parties would be better advised to focus on widespread distrust in politics, deep political dissatisfaction, and belief in conspiracy myths.

Russia’s unprovoked attack on Ukraine is a good example. The AfD seeks to excuse Putin, while democratic parties support Ukraine.

Russia triggered an energy crisis in Germany and caused record levels of inflation in the following twelve months. As a result, the economy slipped into recession, shrinking in 2023 and 2024, and is not expected to improve in 2025.

Yet democratic parties allowed the AfD to benefit massively during this period – especially since mid-2022. Its support in public polling increased from around 10–15% at the end of 2022 to over 20%.

One group in which the AfD is particularly strong is workers – especially those most negatively affected by economic downturn and rising inflation. Among routine labourers and skilled workers alike, AfD support ranges from 36% to 38%.

Despite this apparent popularity, workers – though overrepresented – do not constitute the majority of AfD voters.

Overall, workers make up just under 19% of AfD voters. In other words, for every AfD-voting worker, there are roughly four workers who do not vote for the AfD.

The geography of AfD support also reveals anomalies concerning industry. The AfD gained particularly strongly where industrial employment is high – in West Germany’s industrial heartlands:

- Ingolstadt and Wolfsburg (automotive),

- Salzgitter (steel),

- Ludwigshafen-Frankenthal (BASF), as well as

- southern constituencies with strong medium-sized industrial structures such as Rottweil-Tuttlingen and Schwäbisch Hall-Hohenlohe.

It is especially concerning that many industrial workers in these regions – regions undergoing transformation toward renewable and sustainable production – are choosing the AfD.

Fears of job losses amid weakening industrial production, lack of future prospects, and threats of restructuring or factory closures reinforce this trend.

This is compounded by the social devaluation of industrial work as the industrial share of value creation has declined in recent decades. Many workers strongly perceive this devaluation. At the same time, the everyday concerns of workers seem to find little resonance in progressive democratic parties, while neo-Nazi slogans such as “migrants are the problem” gain traction.

Worse, the concept of the working class increasingly appears to be appropriated by the far right through forms of “exclusive solidarity” – solidarity among Germans only. Dividing the working class works. The conflict is reframed: no longer capital versus labour, but German workers versus migrant workers. This strengthens the AfD while weakening workers.

Hitler’s Nazis understood this. Hence the word “workers” appeared – cunningly – in the party’s official name: the National Socialist German Workers’ Party. There was no socialism and no emancipation of workers – only misery, war, genocide, and destruction in the name of a murderous ideology. In today’s Germany, workers can be politicized under different political banners:

- as an inclusive, solidaristic vertical opposition to the rich, bosses, and owners – that is what unions should do;

- or as an exclusionary opposition directed against other wage-dependent groups such as migrants or social outsiders – that is what the AfD does.

Together with reactionary tabloids, corporate media, conservative politicians, and segments of capital, the neo-fascist AfD promotes what in Germany is known as “desolidarization” – pitting workers against workers, and against refugees, the precariat, welfare recipients, and others.

The AfD – like Hitler’s Nazis – sets the supposedly hard-working domestic “makers” against allegedly parasitic “takers.” This is reinforced by the internalization of an individualized performance ideology promoted by neoliberalism.

Within the AfD’s ideological orbit, being a worker is increasingly defined through downward demarcation – against welfare recipients and refugees – while interest-based politics against the rich and powerful is blocked.

Yet workers tend to prefer social-democratic and progressive parties when these adopt economically radical positions. Class interest can outweigh migration – at least under certain conditions.

Opportunities for political participation – including participation in the workplace – are crucial in counteracting feelings of powerlessness and the individualistic ideology of neoliberalism.

In occupational terms, teachers are among the least likely to vote AfD (only 8%). Lorry drivers are among the most likely (30%), followed by construction workers (26%) and car mechanics (25%).

Donald Trump once said, “I love the poorly educated.” The lower the level of formal education, the more likely support appears to be for Trump – or for Germany’s AfD. The pattern also works in reverse: the higher the level of education, the more likely support is for progressive parties. Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking, for example. On the contrary, Adolf Hitler, for example, had a very limited level of educational achievement.

Among blue-collar workers, 36% support the AfD, compared to only 18% among white-collar workers. Eight per-cent of public servants support the AfD, but a staggering 37% of unskilled workers do so.

Only 12% of workers with high job autonomy vote AfD, compared to 30% of workers in routine production jobs. The AfD is supported by nearly twice as many male workers as female workers.

Workers in jobs with little autonomy show a particularly high probability of supporting the AfD. A lack of democratic participation in the workplace is closely linked to right-wing extremist attitudes and voting behaviour.

A significant decline in experiences of democratic participation at work – especially in eastern Germany – reinforces this dynamic, which helps explain the AfD’s strength there.

In short: stronger unions, greater workplace democracy, and progressive economic policies are essential components in confronting the neo-fascist AfD.

ZNetwork is funded solely through the generosity of its readers.

Donate